China is building new islands in the South China Sea, and equipping them in ways resembling military bases.

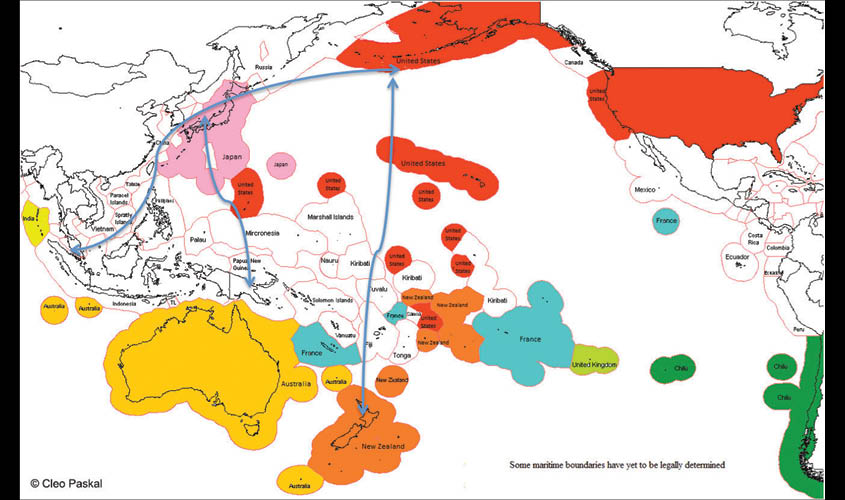

Our strategic map is changing. Literally, as China tries to “break out” of the three island chains that Beijing thinks constrain it.

In the South China Sea, massive Chinese dredgers are building new islands and equipping them in ways that make them look an awful lot like military bases.

Beijing calculates this will help China project power beyond the First Island Chain—islands (including Taiwan and Okinawa) that form the first barrier between China and the wider Pacific Ocean.

Just beyond that, in the Second Island Chain (including Saipan and Guam), China’s engagement approaches vary, from becoming a major investor (and so gaining political leverage) in Saipan, to announcing it has “Guam killer” missiles in an effort to turn locals against the onsite US military bases.

The Third Island Chain, a vast amorphous area roughly between Hawaii, Japan and New Zealand, is also of interest to China. This is the historic maritime front line between Asia and the Americas. It is the extent of Japanese expansion during WWII and these islands were the sites of many of the most brutal battles of that war. It is now home to well over a dozen independent countries, including Fiji, Kiribati, Tuvalu, Tonga, Samoa, Nauru and many more.

Here China uses its usual multifaceted approaches to deepen ties, including investment, migration, loans, scholarships, medical support, military-to-military cooperation and much more. But it also has the ability to bring something unique to the region that could be a dramatic game changer.

The biggest stated concern of many island nations is climate change. Many regional leaders consider it an existential threat. The fear is sea level rise, coastal erosion, increasingly intense cyclones, saltwater intrusion into fresh water systems and more will make their islands uninhabitable. The nation of Kiribati has already invested in land in Fiji in case citizens need to relocate.

The potential for islands to disappear is obviously a human and cultural disaster. It also has strategic implications. Under international law, every inhabited island can apply for a 200 nautical mile (and in some cases 350 nautical mile) Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) off its shoreline, allowing it to exploit fisheries, etc. This means the nation of Kiribati, population approximately 120,000 and made up of widely scattered islands, has an EEZ roughly the size of all of India.

That EEZ is valuable, and is coveted. Earlier this month, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd mooted the idea of entering into a “Constitutional condominium” with Tuvalu, Nauru and Kiribati. Under his proposal, Australia would allow affected citizens of those nations, by his account amounting to around of 75,000 people, to become Australian citizens. In exchange Australia “would become responsible for their territorial seas, their vast Exclusive Economic Zones”.

Rudd’s proposal was immediately rejected by the Prime Minister of Tuvalu, Enele Sopoaga, who said: “The days of that type of imperial thinking are over.”

Tuvalu, already displeased with Australia over its attitude to coal and carbon emissions, now thinks there are some in the Canberra establishment who are trying to figure out ways to benefit from its potential extinction as a nation. Not a great way to make friends.

Additionally, the fact the idea was mooted at all raises a range of questions. Why does Rudd think Australia is the only option for this sort of approach? Why couldn’t India help with adaptation, relocation and maritime protection in a South-South context?

And of course, the big question, if some think sovereign EEZs can be used as negotiating chips, what is China willing to offer to gain access to resource rich waters on the strategic front line between Asia and the Americas? More than Australia would offer, I’d bet.

Which brings us back to the First Island Chain. One thing China can offer, which almost no one else can, is massive dredgers that might obviate the need for some to move in the first place.

Once China’s “magic island-maker” ship completes its primary tasks closer to the coast of China, it can be offered to some of the affected nations of the Third Island Chain to reinforce their shores against erosion.

As a result, China would look like a hero in the battle against climate change—a partner that takes seriously the concerns of the people of the Pacific Islands. Though of course, in the end, Beijing might ask for some rights to a small island of its own (that it could even build for itself) in return for its friendship. And maybe some EEZ access. And so on. And the strategic map changes.

As it happens, Kiribati, Tuvalu and Nauru, the three countries mentioned by Rudd, all recognise Taiwan. If China is the only country to provide them actual options for staying in their homeland, that might persuade them to change allegiances.

As the map shifts, so must attitudes. Nations have a lot more options than they did before. Seeing distress and thinking it’s an opportunity for resource grabs, is morally questionable and extremely strategically short sighted. It risks being like the dog with a bone that sees its reflection in the water and, in opening its mouth to grab the other dog’s bone, loses his own.

The world is changing, geopolitically, geoeconomically and geophysically. True strategic partners need to help each other with real solutions, built on mutual respect, that increase everyone’s security. It’s the right thing to do. For a lot of reasons.

Cleo Paskal is a Special Correspondent with The Sunday Guardian.