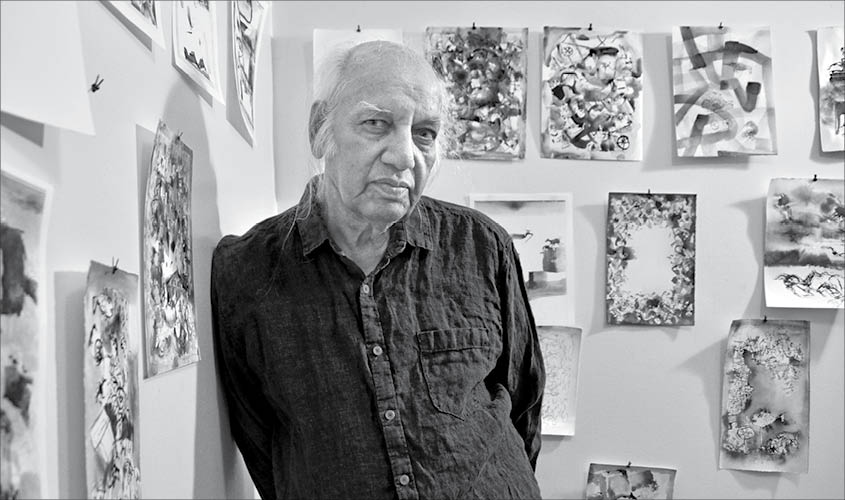

Among the pioneers of printmaking in Indian art, Devraj Dakoji has spent a large part of his life championing a form that has been sidelined by mainstream art. A new exhibition of his prints gives us the big-picture view of his entire career, writes Bhumika Popli.

At Heartbeat of the Void, a solo exhibition by the 74-year-old master printer Devraj Dakoji, there are a couple of prints, featuring rocks and boulders, which remind you of Hyderabad.

Driving into Hyderabad through the Outer Ring Road, one can see grand rock formations on both sides. The prehistoric rocks can also be seen in different parts of the city. Their uneven contours sometimes form shapes that are recognisable and illusive. “When you travel at night these rocks appear as people, sitting and talking to each other,” says Dakoji, who grew up in Hyderabad.

Today, Hyderabad’s heritage rocks are in danger of being wiped out, thanks to rampant construction activity. Also endangered are the organic life forms these rocks support, some of which are suggested by Dakoji’s prints.

A number of environmentalists in the past have made numerous attempts to save these pieces of early history, but to little avail. Most of the rocks are already gone. “As the rocks started disappearing from my hometown, my focus shifted towards nature. I began work on my rocks series in the mid-70s and continued for the next 10 years,” says Dakoji.

Nature as a theme informs Dakoji’s more recent artworks as well. His drawings and watercolour paintings, also on view here, explore a more abstract form. The shapes look like buildings and include fantasy elements. There are images of fish and birds placed atop bicycle wheels.

The artist is a practicing Buddhist, and it was this philosophy that led him to believe that everything in nature needs love and affection to grow. Throughout his artistic career, he has regarded nature with an enquiring eye. According to him, nature will find its way despite the disturbances.

Dakoji is one of India’s most renowned printmakers. He started dabbling in this form in the 1970s and soon committed himself to it. The most prominent exhibitions in India featured his work, alongside that of the other leading modernists. Dakoji also collaborated with artists like M.F. Husain.

Artistic collaborations have always been important to Dakoji, just as they have been central to the history of printmaking. “In Raja Ravi Varma’s time, there were Germans coming to India and collaborating with artists in Bombay. They never used photography. Hence there was no colour compression. They used the technique of chromolithography of using different coloured stone, which matched his painting. But later this practice stopped,” says Dakoji.

As a young artist, Dakoji travelled West, to Europe and the USA, where he learned more about printmaking. He spent most of his time in New York, practising at the prestigious Robert Blackburn Studio, where he worked with local artists. He also spent time as an apprentice here to the renowned printmaker Krishna Reddy.

On his return to India in the year 1996, he set up Atelier 2221 at Delhi’s Garhi village, with a view to training young printmakers. “I set up a studio called Atelier 2221 with Pratibha, my wife, who is also an artist. It was the only independent printmaking studio in India at the time. With some financial support, we imported from England good quality paper and materials required to make prints and bought machinery from the local market,” says Dakoji.

According to the artist, the studio turned out to be a failed venture. Few artists showed interest in it, and eventually the place was shut down. Dakoji himself left for New York, having received an invitation to teach at the City College.

About Atelier 2221, he says, “I worked with Gulammohammed Sheikh, V.S. Gaitonde, and others. We ran it for almost 8-9 years but after that, we couldn’t sustain the enterprise as artists were not responding to it, and we were exhausting our funds for nothing. The medium was new and till date many people do not consider prints as an art medium, but as a medium of duplication, which is very unfortunate. The galleries, too, were mainly interested in showing paintings. Paintings fetch more money. But the good thing with print is that you can reach out to a larger audience, as Ravi Varma and Rembrandt did.”

‘Heartbeat of the Void’ is on view at Delhi’s Art Heritage Gallery at Triveni Kala Sangam till 27 April