Spandita Malik, an artist from India who recently graduated from Parsons School of Design with an MFA in Photography has created some of the most powerful portraits of women I have ever seen. In her new series, titled, Nā́rī ( Sanskrit for woman, wife, female or an object regarded as feminine – also meaning sacrifice), Malik takes portraits of women in India and prints them on fabric from their various regions. She then asks them to embroider on their own portraits, giving them no guidelines as to what they can or cannot embroider.

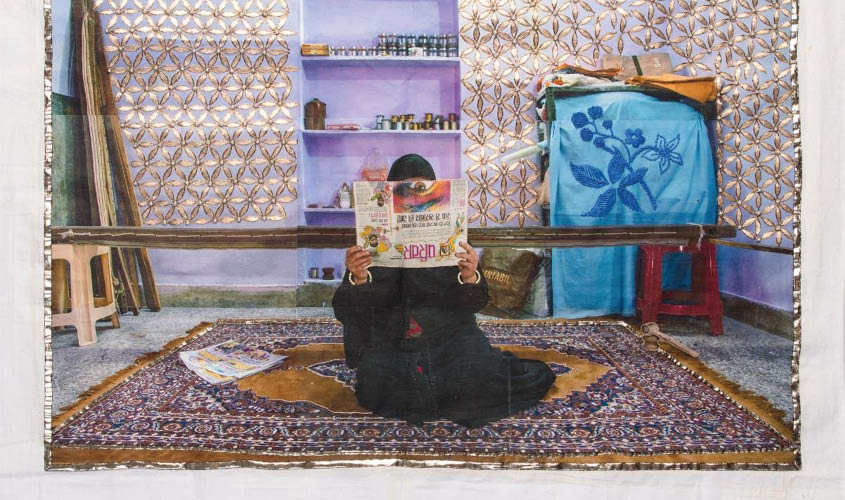

Malik’s portraits of women living in India, who are not allowed to leave their homes or in some cases do not feel safe even leaving their houses, are extraordinary. In one work, the woman not only conceals her entire face with embroidery, she then adds another layer by creating a veil, making her completely unrecognizable. In another work, the sitter shields her identity by holding up a newspaper in front of her face. Where the women have decided not to obscure their identities, one can clearly see their fatigue, strength, and pride.

Q. Did you think your works are more like a journal, documentary or a fictional project? Entering each home, do you have a plan of representing your subjects in prior research or confront the unpredictable aspects of their private life?

A. I believe my project Nā́rī is a synthesis of documentary and fine art. Growing up in India, I often felt that the photography surrounding India, for a long time, was picturesque images of poverty through the lens of the outsider. The way that I grew understanding photography of my country was through a colonised eye. This project became a very important part of my understanding of my country, of the women of my country through a decolonised perspective.

A. I believe my project Nā́rī is a synthesis of documentary and fine art. Growing up in India, I often felt that the photography surrounding India, for a long time, was picturesque images of poverty through the lens of the outsider. The way that I grew understanding photography of my country was through a colonised eye. This project became a very important part of my understanding of my country, of the women of my country through a decolonised perspective.

I was researching rape culture and wanted to interview women in self-help groups, who were also learning to embroider. I heard about women who were not allowed to come to the self-help centres and therefore worked from home. This urged me to go meet with the women in their houses. I did not have a definite plan before entering these personal spaces. All I knew was that I wanted to talk to them about various aspects of patriarchy affecting their lives. I was welcomed into their houses without any fear of me being a stranger. I understood that at the same time I wasn’t scared of being there either. Even as strangers, there was an ease in opening up and talking about the pain that women sometimes understand without having to say it out loud. When I asked them how it was to be a woman in India, they often answered: “you know how it is”.

Q. I found it fascinating that there’s a coherence of women’s embroideries matching their portraits. Did you guide them towards specific fashion patterns or collaborate on a specific vision to embroider on their portraits? Fabrics is a material which is definitely leaning to females. Does your fashion design background influence you to choose the topic related to fabrics?

A. After I interviewed the women I met, I guided them for a portrait in the space that they lived in. While photographing them, I understood that any portrait I took, will always be my representation of them. So, I printed the portrait I took, onto the fabric of the region and gave it to them to embroider the portrait in a way that seemed fit to them, without any guidelines. When I take a portrait as a photographer, I have the power to represent the subject through my idea of them. When I ask the women to embroider their portraits, they take some power from me and represent their portrait through their idea of themselves, therefore, sharing the power.

I travelled to Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, Jaipur in Rajasthan, and Chamkaur Sahib in Punjab. The embroideries that are culturally famous in these regions are chikankari (shadow embroidery); kutch and zardozi; and phulkari respectively. The women embroidered their portraits in patterns specific to the embroidery of the region.

While pursuing my MFA in Photography at Parsons School of Design, I began to reflect on the rich Indian culture of crafts and embroidery that I learnt from my grandmother and mother, and which I also pursued in my undergraduate studies in Fashion Design. There has always been a sense of legacy being passed among women through this language of embroidery and handcraft, to break the oppressor by simple but significant hand movements captured on the fabric, written in thread.

A. After I interviewed the women I met, I guided them for a portrait in the space that they lived in. While photographing them, I understood that any portrait I took, will always be my representation of them. So, I printed the portrait I took, onto the fabric of the region and gave it to them to embroider the portrait in a way that seemed fit to them, without any guidelines. When I take a portrait as a photographer, I have the power to represent the subject through my idea of them. When I ask the women to embroider their portraits, they take some power from me and represent their portrait through their idea of themselves, therefore, sharing the power.

I travelled to Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh, Jaipur in Rajasthan, and Chamkaur Sahib in Punjab. The embroideries that are culturally famous in these regions are chikankari (shadow embroidery); kutch and zardozi; and phulkari respectively. The women embroidered their portraits in patterns specific to the embroidery of the region.

While pursuing my MFA in Photography at Parsons School of Design, I began to reflect on the rich Indian culture of crafts and embroidery that I learnt from my grandmother and mother, and which I also pursued in my undergraduate studies in Fashion Design. There has always been a sense of legacy being passed among women through this language of embroidery and handcraft, to break the oppressor by simple but significant hand movements captured on the fabric, written in thread.

Q. I’m wondering how you changed your mind on the word “nā́rī” after visiting the private spaces? How long have you been working on this project? And you have been interested in the women issues topic throughout your career, do you feel frustrated that those issues still exist or you will have a hope that people can hear your voice to have a change in the future?

A. I had the privilege to be the bearer of the stories these women shared with me, to hear them, to question them, to understand the silences, the pauses, and to have the responsibility to retell, share and pass on the stories.

Nā́rī is a word commonly used in Hindi for a woman. I researched the word, in Sanskrit, nārī means woman, wife, female, or an object regarded as feminine but can also mean sacrifice. I was shocked to learn the meaning, I was also shocked to have understood it at the same time.

A. I had the privilege to be the bearer of the stories these women shared with me, to hear them, to question them, to understand the silences, the pauses, and to have the responsibility to retell, share and pass on the stories.

Nā́rī is a word commonly used in Hindi for a woman. I researched the word, in Sanskrit, nārī means woman, wife, female, or an object regarded as feminine but can also mean sacrifice. I was shocked to learn the meaning, I was also shocked to have understood it at the same time.

I have been working on the project Nā́rī for more than a year. I was born in a family that considered women as equals in an otherwise oppressive and patriarchal society. My mother broke the norms of society, provided for her family and brought me up in an environment free from gender based prejudice. Constantly inspired by her while growing up, women’s right to equality, education and safety became focal interests to me and vital for my creative practice.

At an impressionable age, I heard about brutal gang rape cases on the news very often and the lack of political outrage for women’s rights, made this matter less abstract and closer to home. These incidences not only forced me to believe that in India, a woman is less than human but also urged me to shed light on the stories of the women in India.

While misogyny is hardly exclusive to one country or culture, India bears particularly ghastly symptoms of it. As a woman, I feel extremely frustrated about this, I hope that I can share these stories as much as I can. I also believe that as a country, India is in the middle of a huge political and religious confrontation with our inner faults as a society, and I believe that a new world is on its way, we just need to keep at it.

Q. How would you describe your creative process in one word?

A. Intricate

A. Intricate

- Advertisement -