Alan Turing and Robert J. Oppenheimer were noble souls. Besides being brilliant pioneers of the modern technologies, they had strong Indian connections.

The two most empowering technologies of modern era are the computer and atomic power, fathered by Alan Turing and Robert J. Oppenheimer respectively. Computer, or digital computing to be more precise, underlies almost every advance of modern technology, and the exclusive club of atomic weapons is nearly coterminous with the control of global interplay of political and economic powers. You could argue about the relative significance of economic progress and militarisation of nations, but nation states in 21st century too are covered by national armies, directly or in treaties with other states. The nuclear club zealously guards against admission of new states in its fold. The proliferation of cutting edge technologies in computer and atomic power is closely safeguarded by advanced economic and military powers.

Though it is an absorbing subject in itself, my purpose here is not to dwell upon the chemistry between economics and militarization of nation states, but to draw attention to some parallels in the lives of Turing and Oppenheimer. To anticipate what is to follow, both were contemporaneous, rebellious and brilliant scientists at the progression of computer and atomic technologies, but for different reasons, were not treated justly by the administrative-judicial systems and died in indignity. Both contributed greatly to the victory of Allied Powers in the Second World War. And they had Indian connections in some ways.

ALAN TURING: THE FATHER OF MODERN DIGITAL COMPUTER

Alan Turing was born in 1912. His father, Julius Turing was an officer of the Indian Civil Service with Madras Presidency who rose to become Agriculture and Commerce Secretary. His mother, Ethel Stoney was the daughter of Chief Engineer Edward Stoney, who built the Tungabhadra Bridge. Alan, who was their second of two children, was conceived in India, but born in England. Alan studied at the English Public School. While his parents continued to travel between India and England, Alan never visited India, despite strong parental roots.

THE DECISION PROBLEM

Turing had many feathers in his cap, but here we consider only two. For one, during his fellowship at King’s College, he was confronted with the “decision problem” (Entscheidungsproblem in German- as posed by famous German mathematician Hilbert). The question it raised was: Is it possible in principle to find a fool-proof method or procedure consisting of a finite number of steps to determine whether a given mathematical proposition can be proved from a given set of axioms and rules? It came to be known as the decision problem, the answer to which would let mathematicians grasp how far man can compute with a formal system of mathematics. The question had assumed added importance in view of Kurt Godel having shown earlier in 1931 that our mathematical system is incomplete. By 1936, when Turing presented his paper in response to Hilbert’s question, Alonzo Church had already answered it in the negative (making extensive use of lambda calculus invented by him).

Now, if you are not mathematically minded (just like me), and the decision problem appears too abstract mathematically, here is an interesting turn. Turing answered the decision problem not by complex mathematics, but by simple yet robust logical steps. His paper On Computable Numbers with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem, he used the concept of computation by a machine which read and executed one instruction at a time, and went on to show that irrespective of the logical system, certain set of instructions (program) would lead the machine to go into a loop, and fail to provide a solution. In other words the machine would not halt, and execute the loop indefinitely, which answers the decision problem in the negative (i.e. computation not possible). The hypothetical machine came to be called the Turing Machine. It executes one instruction at a time and laid the foundation of modern digital computer, which works on similar principle, executing a binary code for everything it does. Thus, in providing answer to the decision problem, Turing became the father of the modern digital computer.

DESCARTES, TURING TEST AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

In the first half of the seventeenth century, Rene Descartes had questioned whether thinking machines (simulating Artificial Intelligence) could exist. He distinguished between people and machines but did not reduce his arguments to the philosophy of soul, perception or emotion. He defined a thinking machine in terms of its ability to use language and reason. Over three centuries later in 1950, Turing published a paper entitled “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” which showcased an approach to answer Descartes’s question, in the form of an “Imitation Game” (later called the Turing Test). The game has three participants: (i) a man (ii) a woman and (iii) an interrogator. The participants are located in closed rooms with only a tele printer for communication. The interrogator must find out in finite time the gender of the man while the man tries to fool the interrogator into believing he is a woman. The woman on the other hand, helps the interrogator; but remember, the only mode of communication is the language and reason – there is no other contact or prior knowledge.

Now, substitute the man with a computer trying to pass for a human being and the woman with a human being of either gender helping the interrogator, whose task now is to ascertain whether there is a computer in the game.

Turing had predicted that by 2000 Artificial Intelligence would be so advanced that the human interrogator would not have more than 70% chance of identifying the computer in the Imitation Game. However, despite spectacular advances in the computer science, the first machine to pass the Turing Test was notified only in 2014, as an Artificial Intelligence programmed computer called Eugene Goostman, simulating 13-year-old boy, passed the Turing Test at an event organised by the University of Reading, at the Royal Society of London. Artificial Intelligence however, remains a controversial yet rich field of study.

BREAKING THE CODE

During the Second World War, breaking the enemy code of communication was crucial to real war games. Alan Turing joined the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park in England in 1939. His task was to crack the codes of the German sophisticated encryption machine, Enigma, which coded keyed messages by a complex of electromechanical rotorsthat changed the pathways of circuits underlying the keys. Before Turing joined the Cypher School, the British had engaged Polish services which ran into difficulties because of the German revision of coding procedures. Sometime in 1941, Alan Turing, heading the Naval Enigma Team, succeeded in devising a machine called Bombe that broke the German codes so efficiently, that their numbers ran into thousands on a daily basis. This superiority decisively helped the Allied Forces win the World War. According to some estimates it helped shorten the Second World War by a year or two.

Turing was made an Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, but continued excellence in pursuit of science. In 1951 he was elected to the Royal Society of London.

GROSS INDECENCY

In the 21st century homosexual and lesbian groups are recognized as LGBT community that coexists with heterosexual population in most parts of the world. They are seen to have a biologically different sexual orientation which has been decriminalized. But historically, and in most of the 20th century, homosexuality was considered a serious crime and Alan Turing had a gay orientation, to the horror of social and legal authorities. In 1952, he was convicted of homosexuality- or gross indecency. Although he was spared a possible term in jail, he was sentenced to 12 months of “hormone therapy” – a euphemism for chemical castration. As a convict, he lost his position at the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the British government’s post war code breaking centre.

We can only speculate on how or what Turing would have felt at such developments. He tried to put up a brave front, but left for Manchester and continued to work on the chemical basis of morphogenesis, now conceptualized as artificial life. Not for long, though. On 8 June 1954, he was found dead in his bed, with a half-eaten apple by his body, unattended since a day before, in gross indignity. He had been working on an experiment with cyanide. Either he had committed suicide or accidentally consumed cyanide. Or the secret service agents took his life because homosexuals were considered a security threat, and Turing knew too much.

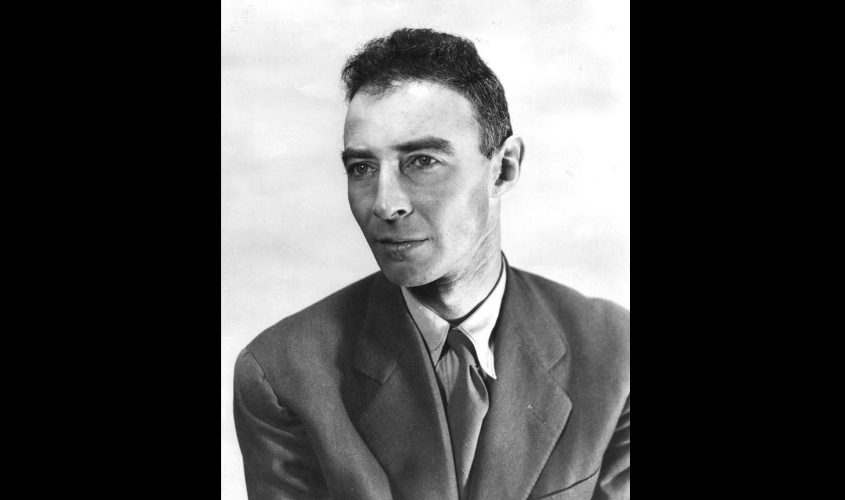

ROBERT J OPPENHEIMER: THE FATHER OF THE NUCLEAR BOMB

Born on 22 April 1904 in New York, Robert J Oppenheimer accomplished his undergraduate studies at Harvard University. He excelled in Latin and Greek, was a brilliant student of physics, and was interested in Eastern philosophy. Oppenheimer had a philosophical Indian connection: He was well versed in Sanskrit and had read the Bhagavad-Gita. In the days following the nuclear bomb test explosion in the Manhattan Project headed by him, he recalled a quote from the Bhagavad-Gita that ran through his mind upon seeing the bright radiance of explosion:

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed… A few people cried… Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the prince that he should do his duty, and to impress him takes on his multi-armed form, and says, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

It is unlikely to have been an off the cuff quote. He was making sense of what the success of his project had brought the world to. It is also clear that the quote is not exact, but his translation based on of his recall of the episode in the Bhagvad-Gita (Chapter 11, Verse 32). And this makes his philosophical connect with the Bhagvad-Gita even more authentic.

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

The story of the first nuclear bomb began with the inception of the Second World War. The news, that German Nazis led by Adolf Hitler were into developing a nuclear bomb, reached the USA. The UK too was attempting to develop the nuclear bomb. But in the USA, pioneers of physics, many of them having left their German home land because of the Nazi oppression, began to endeavour for the nuclear bomb. In 1939, Enrico Fermi met US Naval authorities and Albert Einstein wrote to President Roosevelt favouring steps to develop the nuclear bomb. That was a couple of years before 1941, when the USA formally joined the War.

Robert Oppenheimer at the time had held teaching positions at the University of California and the California Institute of Technology, and was eminently involved in theoretical research on the possibilities of making a nuclear bomb. From here, he was picked up for the Manhattan Project in 1942, for crafting a nuclear bomb literally on war footing, before the Nazis did it.

PROJECT Y

Major General Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was the director of the Manhattan Project, and also oversaw the construction of massive civil engineering works. Robert Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, named Project Y that designed the nuclear or atomic bombs under the project.

The Los Alamos Laboratory scientists worked with excellent team spirit which is evident in the trials and tribulations leading to the design and testing of devices. The Manhattan Project director Major General Leslie Groves even approved a plan for the exigency of failure of a fully successful explosion. Thus was constructed a steel container 25 feet long and 10 feet in diameter, with 14 inches thick steel walls and weighing 214 tons, called Jumbo. Its designated strength was estimated on the basis of calculations of pressure from the expected 1st stage of explosion – which is in fact a TNT explosion that compresses the fissile plutonium so enormously as to ignite a nuclear chain reaction leading to implosion of plutonium. If the TNT explosion failed to implode plutonium, the steel container would prevent the expensive radioactive metal from being scattered and lost, and becoming a health hazard. If however, plutonium implosion (2nd stage explosion ignited by the TNT explosion) worked, the Jumbo would be vaporized. The Jumbo was built because Major General Grove was concerned how the possible loss of plutonium could be explained to the Senate, on the heels of a failed bomb test.

As Oppenheimer’s team gained confidence in the bomb’s design, Jumbo was not used. It still lies near ground zero – its ends having been blown off subsequently by the US army.

THE TRINITY TEST

The Trinity Test, as the nuclear detonation was called, was successfully conducted on 16 July 1945, in a remote desert near Alamogordo, New Mexico. Soon after, two nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. One of them, a uranium-based design was called the “Little Boy” and the other, a plutonium-based design called the “Fat Man”, both developed by Robert Oppenheimer’s team at the Los Alamos laboratory. The destruction they wreaked in Japan brought it to its knees. Germany was already suffering significant reverses spurred on by Alan Turing’s Bombe decoding encrypted German war time communications. It is no exaggeration to state that the victory of the Allied Powers was built upon the scientific prowess of Turing and Oppenheimer. The Axis Powers surrendered in good measure as their scientists could not keep pace with Turing and Oppenheimer. The Second World War came to an end.

OPPOSITION TO THE HYDROGEN BOMB

Following the World War II years, Oppenheimer joined the Institute for Advanced Study in 1947 and continued as its director until 1966. He was also appointed as the chairman of the prestigious General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission, from 1947 to 1952. Steered by Oppenheimer, the Committee opposed development of the hydrogen bomb (Nuclear bomb based on more destructive fusion technology). Perhaps his scientific brilliance for nuclear weapons was confronted by his pacifist instincts. He voiced his preference for the use of nuclear power for peaceful purposes. Nevertheless, it shocked many Americans with strong nationalist instincts. Oppenheimer’s background was dug up and to his misfortune, the FBI under its first director J Edgar Hoover had earlier trailed him for his pacifist left wing sympathies in the forties, even as he was sought after as a nuclear scientist.

In 1953, a military security report indicted him of past association with Communists, and of opposing the hydrogen bomb project. A security hearing followed, and although charge of treason did not sustain against him, yet the hearing committee found him unfit for access to military secrets. Consequently he lost his contract as adviser to the Atomic Energy Commission, and was divested of other official privileges. Oppenheimer lived a dejected life thereafter, a pale shadow of his proud persona.

However, a decade later, in 1963 President Lyndon B. Johnson restored some of Oppenheimer’s honour and embellished him with the Enrico Fermi Award of the Atomic Energy Commission. But his health was already failing. Oppenheimer died of throat cancer in 1967. He had personally never recovered from the dishonour meted out to him.

WHY THE HEROES FACED INDIGNITY: KARMAS OR INDIFFERENT UNIVERSE?

Turing and Oppenheimer were noble souls besides being brilliant fathers of modern technologies. Engrossed in their pursuits of knowledge, there is no account – at least not in public domain – of any harm they ever intended or inflicted on anyone. Questions about their treatment by the powers that be have haunted me from my younger days: Why did they suffer humiliation, indignity and spiteful death? They faced horrid circumstances stoically – but why did they have to face dishonour? What touches me is that Oppenheimer had read and certainly understood Lord Krishna’s Gita, which connects fate and justice in this life to karmas in past lives. It gives a little comfort to rationalize injustice received in this life as a consequence of the karmas of past lives. But the other view comes to grips with this aspect of reality in the words of a brilliant scientist, Carl Sagan: “The universe seems neither benign nor hostile, merely indifferent.”