The failure so far to change Article 9 in the Japanese Constitution that was imposed by the US occupation forces after World War II has rankled PM Abe, and he sees that among his failures despite many successes.

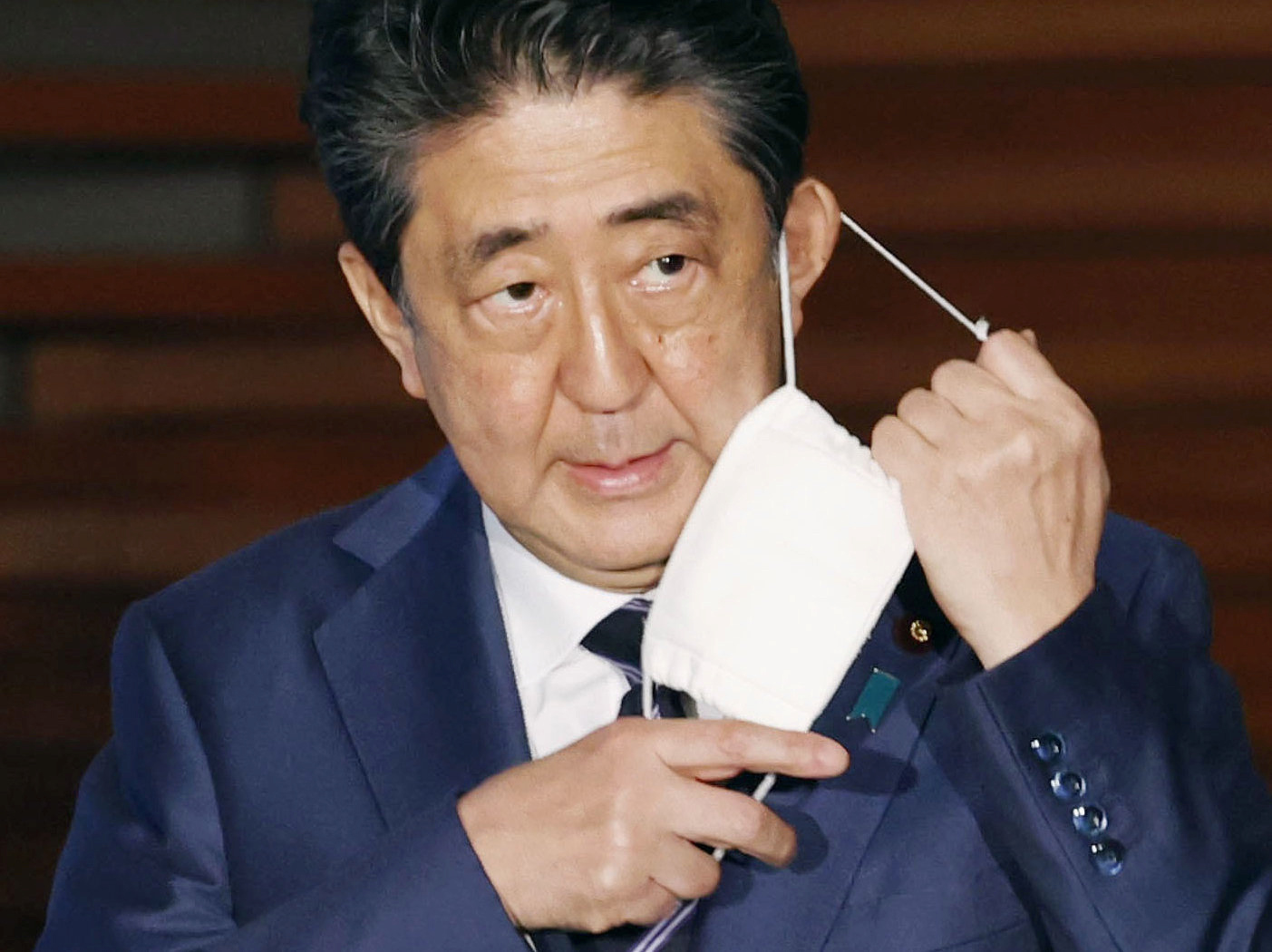

TOKYO: The first time Shinzo Abe retired as Prime Minister was in 2007, when he had an exacerbation of the ulcerative colitis (UC) that has been with him since his teenage years. This time too, the officially stated reason is the same, that he has to take care of his health and now change the treatment he was on earlier to a monoclonal antibody, Adalimumab or Infliximab. That is certainly all true, but then as well as now, there have been other factors that may have been important as well. Given that UC is certainly not a terminal illness, but a debilitating one nonetheless, yet given the longevity of the Japanese—over 70,000 people are living aged 100 and above—one may see Abe once more in the saddle after another pause. The reason is that Shinzo Abe and Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike are the two most dominant figures on the Japanese political scene and they both tower above everyone else. Governor Koike is not currently part of any major political party. PM Abe is strongly supported by the omnipresent Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), that even changed its own party constitution to permit Mr Abe extra three-year terms. That is how Shinzo Abe, now only aged 65, already became the longest-serving Japanese Prime Minister. Abe will remain an MP from Yamaguchi Prefecture where he is beloved and undefeated in nine parliamentary elections.

The genuine warmth between Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Prime Minister Abe is well known, with PM Modi even having been invited for a rare private dinner to Shinzo Abe’s holiday villa in Narusawa, near Lake Kawaguchi located in the foothills of picturesque Mount Fuji, the first non-Japanese to be so invited. Abe has consistently advocated strongly on behalf of India, even to sceptical corporate honchos who were briefed by bean-counting executives that “India is a difficult place to do business”.

Shinzo Abe’s maternal grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi was overwhelmed with emotion when as a post-War Japanese PM of a then-defeated nation, that had nonetheless been an ally of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army, came before admiring crowds in India. Shinzo Abe, when out of office in 2011 was welcomed with open arms as he addressed a gathering of the Indian Council for World Affairs filled with JNU and other faculty. Abe has never forgotten that special feature of India (that he also heard about earlier as a child on his grandfather’s lap). Indeed, BJP National Executive Member and Rajya Sabha MP, Dr Subramanian Swamy pinpointed that unique aspect which makes India attractive, by pointing out on a video call to thousands of young scholars and scientists contemplating a return to India to contribute to making India a great power someday, that India permits multiple personal and professional failures cheerfully along the way, unlike harsh situations in some industrial countries where “gyanis” (knowledgeable persons) and “tyagis” (those who live not merely for the pursuit of wealth) are not necessarily always welcomed nor respected.

PM Abe has been a transformational figure—his vision of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” was embraced by most of Asia barring one notable country. His quality infrastructure initiative in Asia and Africa countered the debt-trap diplomacy of others, and his “Three-Arrows of Abenomics” revived a then-moribund economy. In the Covid-19 crisis, he stepped up with major stimulus measures, putting cash into the accounts of individuals and companies. PM Abe cooperated effectively with both the permanent bureaucracy as well as with outside scholarly advisors like Prof Tomohiko Taniguchi, who worked with Abe on his “Confluence of the Two Seas” speech to Indian Parliament on 22 August 2007, and multiple other prescient strategic moves thereafter. That set the stage for impetus to the Quad and Quad Plus and linking the Indian and Pacific Oceans—the title of Mughal Prince Dara Shikoh’s year-1655 book was used as the headline of PM Abe’s speech.

THE NEXT PM

Japanese politics is, broadly speaking, a hereditary and elitist business with the sons and daughters of politicians and the wealthy ruling the roost. Abe himself is related to multiple political figures including two Prime Ministers, maternal grandfather Kishi and Shinzo’s great-uncle Eisaku Sato; and Shinzo’s late father Shintaro Abe was a well-regarded Foreign Minister, who advocated education and mutual understanding as priorities. Similarly, Yukio Hatoyama and his grandfather Ichiro were both Prime Ministers, and indeed the other grandfather of Yukio’s founded the now giant Bridgestone tyre company, where Yukio’s mother was the sole heir making them among the world’s wealthiest.

On the race to elect the next PM, official factions within the ruling Liberal Democratic Party are very important—LDP factions meet regularly in study groups, each forming temporary alliances with other factions in order to achieve power, including Cabinet positions. The LDP’s three largest factions, respectively led by former LDP Secretary-General Hiroyuki Hosoda, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Taro Aso and former LDP General Council Chairman Wataru Takeshita (younger brother of late Prime Minister Noboru Takeshita), have been outmanoeuvred by LDP Secretary General Toshihiro Nikai, who heads a faction of nearly 50 lawmakers, and who has stage-managed the campaign to elect current Chief Cabinet Secretary, Shinzo Abe’s closest aide, Yoshihide Suga as the next Prime Minister. A deft manoeuvre, citing the emergency situation of Shinzo Abe’s sudden resignation during the pandemic, was used by Secretary General Nikai in the General Council of the LDP, citing precedent, to deny voting rights to unelected LDP members from the regions who largely favour former Defence Minister Ishiba, thereby all but assuring victory to Suga. Thus, Nikai, seen as an ageing warhorse by some, has delivered a masterclass in hardball politics at a critical moment in Japanese post-war history. The heavy weightage given to Members of Parliament in selecting the next Prime Minister in voting scheduled for 14 September will likely ensure victory for Suga, who is strongly backed by MPs. Naturally, as part of this deal there is little doubt that once Suga becomes Prime Minister and titular leader of the LDP, Nikai will retain the post of Secretary-General, the powerful operational head of the ruling Party that constitutes the overwhelming majority in the ruling coalition. This whole arrangement is only to serve out the remaining one-year term of Abe. Next year, the process will have to be redone all over again, with a general election to follow as well. However, the Japanese Parliament is in many respects different from India’s, with the Japanese PM having to answer a plethora of questions in committees, especially the budget committee. Indeed, decades ago, then-PM Ichiro Hatoyama was even blocked from using the restroom amidst continuous questioning by parliamentarians—something that might be hard to fathom for Indian or indeed modern Japanese legislators.

Among the factors speculated to have played a part in Shinzo Abe’s resignation decision includes the rising criticism about Japan’s Covid-19 cases, now totalling nearly 71,000, with 1,339 deaths. If only the hyper-critical media and a significant proportion of the Japanese population had the same patience as in many other countries with far higher Covid numbers, Shinzo Abe may not have felt compelled to resign. Further, the failure so far to change Article 9 in the Japanese Constitution that was imposed by the US occupation forces after World War II has rankled PM Abe, and he sees that among his failures despite many successes. Abe has argued that if Japan were attacked it needs every means to defend itself as “a normal nation” and for that, Article 9 must be amended. But the Japanese people who suffered immensely during the War and in the aftermath of defeat, are in no mood to change the peace Constitution, with one proviso—that same currently peace-loving people would become extraordinarily fiery were either the PRC or the DPRK to fire a missile that actually landed on Japanese territory. Overnight, Article 9 would be thrown in the dumpster by Parliament. And indeed, a health-revived Shinzo Abe might just be back then, once again.

Dr Sunil Chacko holds degrees in medicine (Kerala), public health (Harvard) and an MBA (Columbia). He was Assistant Director of Harvard University’s Intl. Commission on Health Research, served in the Executive Office of the World Bank Group, and has been a faculty member in the US, Canada, Japan and India.