Edited by Rakshanda Jalil, a literary historian and Debjani Sengupta, a lecturer of English literature in Indraprastha College in Delhi University, the book offers an in-depth look into the life and times of 1971.

A brown coloured paperback that looked from a distance like a reporter’s notepad landed on my desk earlier last week. A close look revealed it was a book on Bangladesh and had writings from 1971. I found the effort fascinating because not many books have hit the stores on the 1971 liberation war in East Pakistan that eventually gave birth to Bangladesh, there should have been some more. Edited by Rakshanda Jalil, a literary historian and Debjani Sengupta, a lecturer of English literature in Indraprastha College in Delhi University, the book offered an in-depth look into the life and times of 1971.

The book, interestingly, is laced with real life stories from East Pakistan and essays and also some poetry, reminding many of the days when both Bengal and East Pakistan were in bloody turmoil. India witnessed the Maoist movement at the base of the cloud-kissed hills of North Bengal and in tea gardens around Naxalbari, a sleepy hamlet. It was the setting of a violent, failed revolution that many claim was the incubator of India’s epic class war. And then, across the border, there was violence of unprecedented nature as Indian armed forces – aided by freedom fighters of East Pakistan – clashed with Pakistani forces, and eventually gave birth to a new nation, Bangladesh, that gained independence from Pakistan.

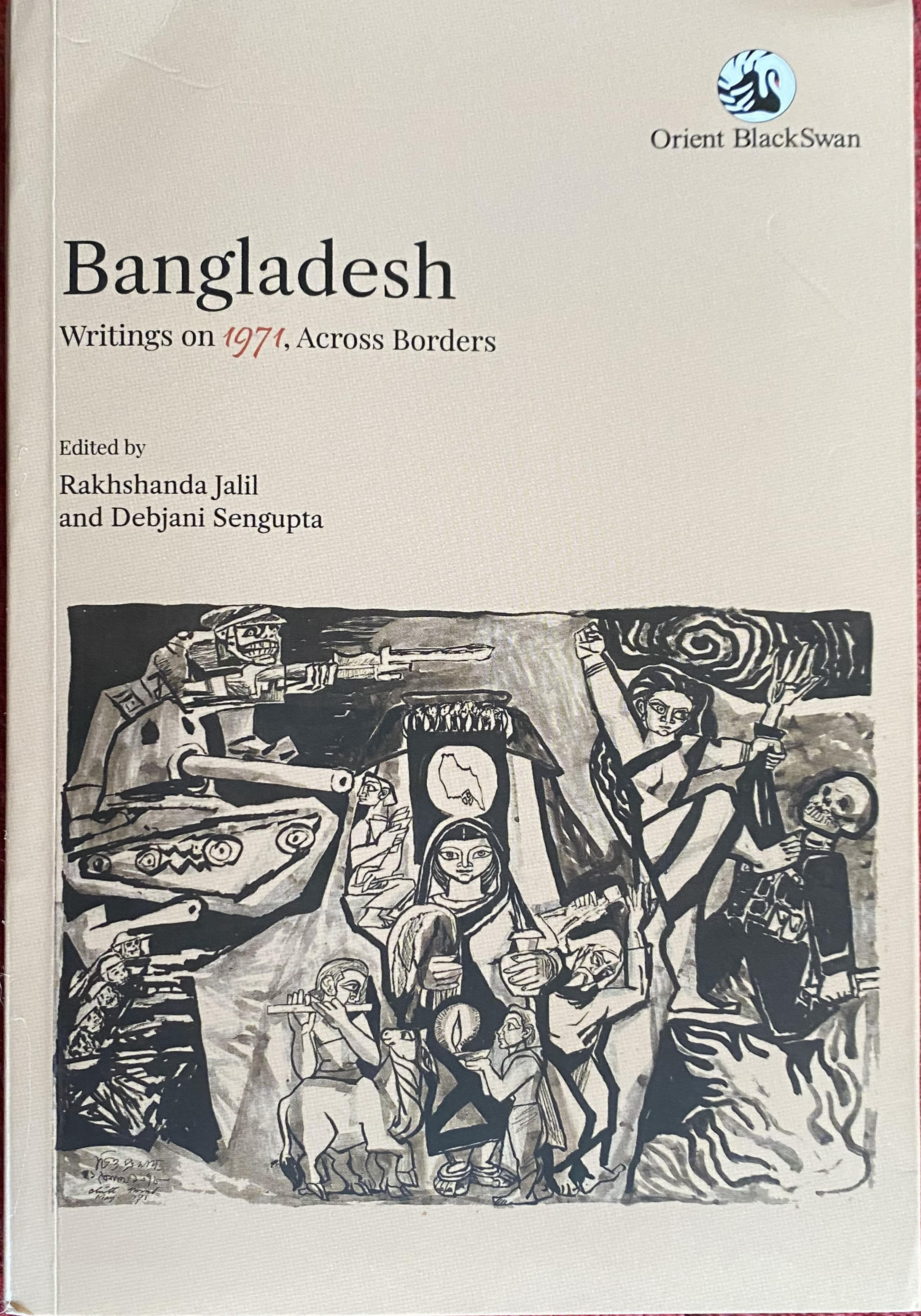

Bangladesh, Writings on 1971, Across Borders, painstakingly explains the human cost of the new nation that was born more than five decades ago. The book, published by Orient Black Swam, takes a serious account of what was won and what was lost.

I read in the book from a chapter that narrated those horrifying days, horrifying nights. A nation at war is tough news. So it read like this: “It was the night of 25th March. The Pakistan Army stationed at the library was shelling the students hostels in Dhaka University. Iqbal Hall and Jagannath Hall were falling apart. The rusted water pipe dislodged from the wall, water from the overhead tank gushed forth to the ground. Some of the boys living on the second floor ran towards the stairs. Others chose to swing down the ground from the branches of trees outside their rooms. People ran helter-skelter into the dark. Dense clouds of smoke rose from every direction and blackened the moonlit night.”

The book, throughout its chapters, explained the contradiction between exalting and forgetting what happened in 1971 and why the liberation war in Bangladesh still remains a contested space, fully charged with emotional and psychological intensity after five long decades. The book reminded me of William Faulkner’s words: “The past is never dead, it is not even past.”

The authors very rightly said in the book discussions on the 1971 liberation war in East Pakistan hardly occupied the Indian mindspace. There should have been some serious documentation of the war that was fought. Now, more than five decades later, it becomes tough to piece together tales of those dark nights, the struggles of people, the pains of hundreds and thousands of women who were raped by soldiers of the Pakistan Army and gave birth to war babies. Yet, the book makes a genuine effort to paint the canvas.

I liked the story of Shankhari Bazar in old Dhaka, home to the Hindus of East Pakistan. I had visited the cacophonous neighbourhood and heard the story of Khejur Banu, or Tapati.

It was at the Shankhari Bazaar, a stretch of narrow lane full of brick buildings, the first spark of the uprising in 1971 was ignited. It is one of the oldest areas in Dhaka.

Khejur Bani and her family used to run a sweet shop, every day she would heat up almost 10 litres of hot sugar syrup for her rosogollas, considered the king of sweets. She knew Dhaka was burning, there were vultures in the skies. One day, she was told marauding soldiers of the Pakistani Army are slowly encroaching on Shankhari Bazar. They had parked their tanks at the entrance of the lane, and were pushing the soldiers with bayonets fitted on the muzzle of their guns.

Khejur Bani knew she was alone but not afraid. She was bold. She packed her family to a house some furlongs away. And then picked up the hot syrup and went to the roof. She waited for the soldiers to come close and then she poured it all.

There was total cacophony, the soldiers – many burnt – ran for cover. Their commanders also panicked, and they immediately withdrew the soldiers. Encouraged by Khejur Bani, other women threw hot water, crossed as many as 30 rooftops and disappeared. It was almost like Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala, the supreme power of womenfolk taking on a tyrant ruler.

The house where Khejur Bani lived is still there. It is an ordinary house of an extraordinary woman. Cacophonous Shankhari Bazaar remembers Khejur Bani, every hour of the day, month and year.

Jalil and Sengupta’s meticulously edited work is a good read, it highlights the complexities leading to the war, its numerous tragedies. I liked Sengupta’s translation of Bimal Guha’s Ekattorer Kobita that translates into The Poetry of 1971. The last paragraph is just haunting:

“Today with magic prayers, I place these poems on the soft grass

They are now lively, self determined bullets

That travel in all directions through the ether

Through the secret radio Freedom Bangla

Through voices that thunder and roar

In the homes of Bengalis, in the war camps

Today, poetry has waged a war of freedom.”

And then, Jalil summed up the book with her brilliant translation of Jan Nisar Akhtar’s 1974 poem Fateh Bangla which translates into The Bangla Victory. I thought of picking up the first paragraph:

“Whenever there’s cruelty in any corner of the world

We have raised our voices saying: Stop this bloodshed

Stop this incantation of your dirty politics

Stop this oppression, this cruelty, this madness”.

This is a slice of history every Indian must remember, and reflect. The book is indeed a very powerful retelling of the story of one of the bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century. Sadly it is a largely unacknowledged event. A brilliant read.