Age-old barriers are still put in place for the menstruating period. No cooking, in fact, no entry into the kitchen.

Touch. Distance. Infection. Confined. In the era of Covid, a pre-occupation with these words has become a commonplace malaise of a kind. All rooted in well-informed science. Rewind to ancient practice and it all becomes superstition, blind faith.

The most commonplace biological function of a ripened female body, menstruation, is surrounded by myriad beliefs in all societies with long histories. None of it falls in the domain of science.

For starters, there is a belief that a woman is never impure. The reason: Every month, her body is cleansed of all impurities. This exalted belief is quite at variance with a woman’s otherwise status in the same social space. The reality, even today, remains perplexing. Even in urban households, the concept of a menstruating female (dirty/unclean) near pickles is still taboo for many. The pickle is bound to turn bad.

Zero down to semi-rural India, an interior story belonging to a forever ago time that could go back thousands of years. The rules for a married menstruating woman are still strictly adhered to. What exactly does it entail? It is an intricate story.

Uma told me that “Each day of the first three days is dedicated in the name of a particular Goddess. On the fourth day, she is purified. I had read about this long ago. Though people don’t know much about it now.” I asked her: which Goddesses? She had forgotten. So, off she went on a “research” spin, taking her to an old book in her mother’s home.

She reverted with the specific names: Day 1: Chandalini, the Outcaste; Day 2: Brahmaghatini, Slayer of a Brahmin; and Day 3: Dhobin, a Washerwoman. A quick check on Wiki confirms the definitions with a reference to the ancient text, Skanda Puran, but not all the names, except the first. Further Googling is a rather frustrating exercise.

Age-old barriers are still put in place for the menstruating period. No cooking, in fact, no entry into the kitchen. So, I asked, if the mother-in-law is physically dysfunctional or has died and there is no other female, then what? The simple answer, “Either the father-in-law will cook himself or neighbours will provide food.” The menstruating woman is provided food at her place of confinement. She is expected to stay without her “bindi” and “sindoor” during this time. And wash her hair on the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 7th day of the cycle.

For Uma, this is the best part of the month. Rest, television, lolling around. “This is my free time!’, she says with a giggle and laugh. Unlike before, as Uma clarified, “Until the previous generation, the women were made to stay in the cowshed during this time.”

Similar but more complex rules govern the period after a child is born. The higher you go in the caste order, the more intricate to the smallest detail. (It varies across the country as well.) For this Himalayan community, it is a 22-day lockdown involving partial relaxation of rules in the second phase. No touching of the new mother or the infant. If by mistake, touch occurs, immediate scurry to sprinkle cow urine, considered a purifier-excellent. Separate vessels are kept aside to serve food to the mother. Water is kept for cleaning them up.

This is valid till the 11th day, when the infant will partake in a naming ceremony, “naamkaran”, celebrated with much fanfare. After which, mother and infant can be outside anywhere, but not in the kitchen. Even if it is the peak of summer, the mother must continue to wear warm clothes and cover her head with a cap or scarf. In some families (castes), for these 11 days, a perimeter of cow dung is drawn around the bed. One line for a girl and two lines for a boy. Then again, the new mother can start eating normal food after 20 days if it is a girl and 22 days when it is a boy. The ground rules of preference are laid down early enough.

I have my own personal strong recall about menstruation.

I had reached the interiors of tribal Bastar with a film crew. The evening prep meeting with village bosses and the shaman was scheduled. As we neared, a man raised his hand to stop. He whispered something to the person next to him, who came across to take our boss aside and whisper ahead. The message was, I cannot join in because an auspicious welcome ritual will be performed. For sure, I was in the middle of my menstrual cycle.

A similar incident occurred at Manikarnika Ghat in Varanasi, site of the eternal funeral pyres. The Dom told our boss that I will have to go to the terrace and not come near the funeral pyres. Yes, I was in the middle of my cycle.

The question, how in the heavens did they know, has never been answered.

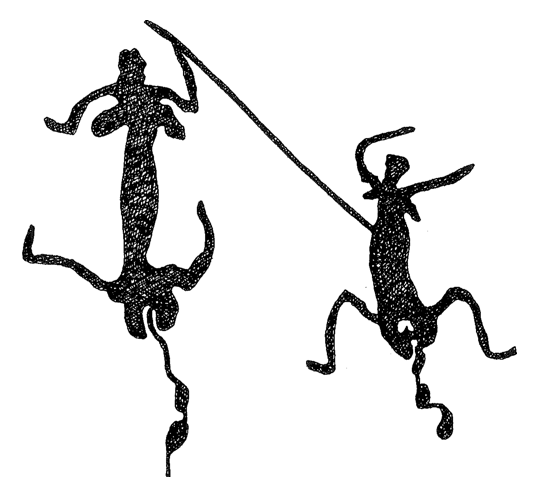

Age-old instincts and perceptions morphed into “regular” practice became part of “daily life”, shrouded in mystery and myth bordering on ritual and religion.

Today, post-Covid, the takeaway is the New Normal. Will it be a while, or never, that we go back to welcoming guests into our homes, hugging, kissing, and all that? Touch. Distance. Infection. Confined. The New Normal.

Looks like the dividing line between blind faith and science got blurred. The reasons and logic of each being debatable.