Premising an entire narrative on fallacious claims, a powerful imagery of the ‘lungs of Mumbai’ being under attack was created.

One of the first decisions taken by the newly instated Maharashtra Chief Minister was to veto Uddhav Thackarey’s decision on the Aarey shed plan. This news sent me down the memory lane in 2019 when Mumbai witnessed a series of protests by citizens, civil society activists, and celebrities against the clearance given to the Mumbai Metro Rail Development Authority (MMRDA) to fell 2,700 trees for the proposed Metro-III Car-shed construction at Aarey colony. The protests, under the banner “Save Aarey”, triggered an avalanche of articles, blogposts, videos and images showcasing citizen sentiment against this decision. For a reader, who was extensively following this news from the outside, it was a clear dictum against a brutish action meant to choke the lungs of Mumbai.

On the other hand, the campaign in defence of the project #AareAikaNa (translation: Hey! but hear this out) by Mumbai Metro could not attain traction on social media. The fact that the protests were met by a counter movement by citizen groups in favour of the project, remained oblivious to the popular imagination. As the issue re-surfaces, this article is an attempt to point out the incongruities that have rigged the discourse on Aarey and raise larger questions on how opinions should be formed on such matters.

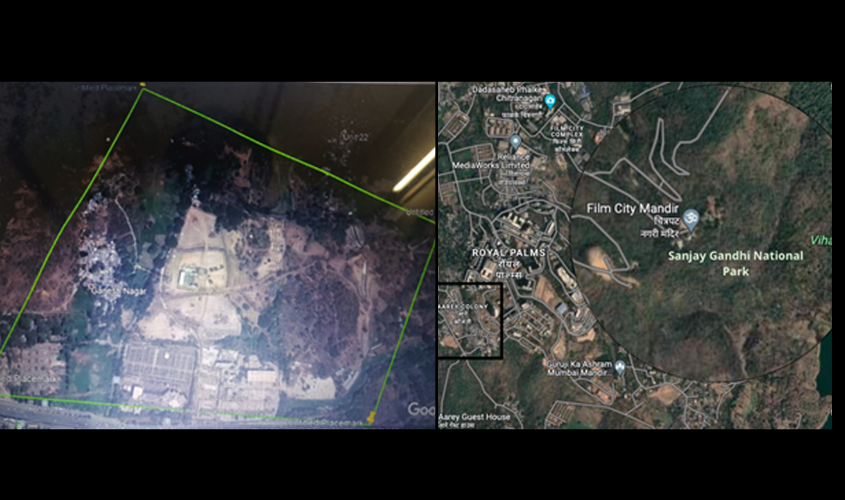

The act of generating numbers with deterministic means is the very first inaccuracy in this discussion. People and agencies have incessantly quoted the absolute number of trees being chopped, while the picture is better captured by a percentage figure that stands at 0.2% of the total trees present within the Aarey forests. It is to be noted that about 461 trees would be transplanted in the vicinity. The confounding of the Aarey milk colony, of which about 30 Ha or 2.5% would be required for the metro shed with the 11,687 Ha of Sanjay Gandhi National Park (SGNP) is yet another error in the discussion. The figure given with this article illustrates this.

Premising the entire narrative on these fallacious claims, a powerful imagery of the “lungs of Mumbai” being under attack was created. MMRDA repeatedly argued that about 80% of the land that would be used for the shed harbours no trees, but nobody heard. And when calculations showed that the astronomical environmental benefits of the metro would easily compensate for the trees being lost, activists furthered another objection. It was argued that the lives of the tribals inhabiting the area was put under siege due to the project. It is true that the Warli tribes that live along the forests are one of the few urban forest dwellers extant in our country and protecting their rights is of paramount importance. But the story is seldom so simple. Around 80 families in the Naushchapada hamlet of Aarey colony have already been rehabilitated to flats on the other end of Aarey colony. But the unavailability of land records or ownership documents make it extremely difficult to tell the tribals from the slum dwellers. Further, the absence of community forest rights and their systematic displacement over the years have further complicated the situation. The land on which they live is essentially government land leased out to them. Thus, their eviction is not in contravention with any law. Having said that, it is important to ensure that the due process for compensation and rehabilitation of the project affected people are followed.

The Aarey episode can be a great lesson in the field of politics and public policy. For the former, one needs to ask this question: how does one incident of deforestation engender a resolute movement in a city that has nearly always struggled to strike a balance between sustainability and development? One can obviously credit this to a heightened sense of awareness, but has it also got to do with an overarching elite participation? How is it that citizens worry about the cutting of 2,100 trees in the Aarey colony but not worry about the illegal encroachment in the vicinity of the Borivali National Park or an 8-lane highway that cuts across the Sanjay Gandhi National Park? And why does one have to almost fish out the state’s stance on the matter, while the stand of the protestors is widely available on all medium?

And the lesson in policy planning is to always look at issues from an empirical cost-benefit perspective. Aarey is one such instance where the government has eschewed a populist stance for a decision that maximises good. Mumbai has a sorry state of public transport, making its quality of life the worst amongst the metropolitans. The cost of axing some trees today far outweigh both the social and the environmental gains that the city and its dwellers will witness in the future. And this complemented with veracious information should be the biggest criteria to determine whether you pick “SaveAarey” or “AareAikaNa”.

Sakshi Abrol is Policy Manager at Nation First Policy Research Centre, a Delhi-based think tank.