Maid in India

Tripti Lahiri

Aleph Book Company

Price: Rs 599

Pages: 304

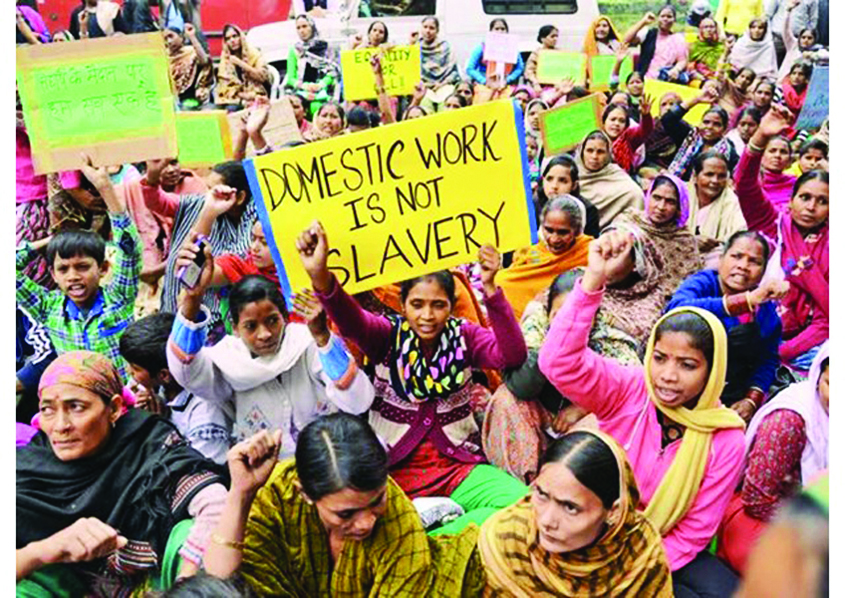

Inside the rich man’s abode, things can be stinky. At Mahagun Moderne, a luxury apartment in Noida, the stench travelled a tad too far on 12 July when the employers at one of the flats allegedly beat up their 26-year-old domestic help. In their defense, the concerned madam and the sahib accused the maid of stealing and manhandling. The narrative was beginning to unfold, but the memsahibs and the maids had already gone to war, laying bare the fault lines of class and social mobility that constitute the characteristics of the urban life.

To say that Lahiri’s work was meticulously researched with an accurate, incisive reportage would be downplaying what she has produced—powerful stories from the villages of India—from Bengal to Assam to Delhi’s poor and posh areas which cut through the readers’ social conditioning like a sheath of light. The stories are more than a piercing account of the humiliation that maids are subjected to; Lahiri brings out the dynamics of socio-economic class that play out in their seemingly ordinary lives every time there is a “matchmaking” meeting between the maids and the employer behind the closed doors, every time that a maid is rebuked for not learning how to “hold a glass of water” by the maid trainers—an industry spawned by the affluent’s insecurities and vanity—and every time that a maid goes missing and is never found. One of the maids in Lahiri’s book is asked a question by her prospective employer living in the towering Magnolias: “Food or cleanliness?”, and the maid, the likes of whom can survive for a month on the amount a family like the owner’s spend on a casual meal in a high-end restaurant, chooses the latter. And she is shown the door.

The account was a deja-vu, an instant reminder of an incident where in the same Magnolias, on a visit to one rich man’s abode for a project in 2015, a maid committed a very committable mistake of dropping a glass of water. It wasn’t her fault in the entirety, but a look at the owner’s face and I could tell the girl was set to draw some share of his anger later. The glass was made of unbreakable steel, if that helps not justifying the owner’s wrath.

Lahiri’s style of writing is captivating. She peppers her stories with a wealth of analytical details and personal observations, exposing how some maids survive in a set up that gives them a limited access to rights and wages, and in the process, ends up showing the mirror to our own ugly selves who obliterate the path of justice for them.

“People who claim to be free of caste bias don’t allow women who clean bathrooms to cook for them, citing hygiene. And left-leaning professors at elite Delhi universities, who usually lament the effects of privatisation and unfettered capitalism on the Indian workforce, suddenly highlight the importance of paying the ‘market rate’ when they think a friend is paying her maid too much,” she writes.

One of the maids in Lahiri’s book is asked a question by her prospective employer living in the towering Magnolias: “Food or cleanliness?”, and the maid, the likes of whom can survive for a month on the amount a family like the owner’s spend on a casual meal in a high-end restaurant, chooses the latter. She is shown the door.

Maid in India is an exhaustive account of not only the domestic workers, but the maid placement agencies, cooks, gatekeepers and social workers. Lahiri does a great job in bringing out the plight of the workers and the real flaws in the system without making the read preachy. In a pertinent note, she mentions how the Delhi government started regularising recruitment for domestic workers through placement agencies in 2014, but did not completely follow it through. She touches upon the issue of minimum wages, noting the Delhi government’s latest bid to increase the minimum wages for unskilled, semi-skilled and skilled workers by 37%.

Scepticism and complications around immigrant maids being hired, “allegedly” abused, and being faced with the complexities of the “legal process” to slip out of the situation with compensation has the tendency to take a rather ugly discourse. Lahiri picks up one such case of an Assamese maid who alleged she was raped by the owner of the house repeatedly when the other family members were out. The case, by the Indian legal standards, escalated after the Nirbhaya rape case of 2012, and was moved to a fast track court. On the day of the hearing, however, the maid confessed to lying about the rape, alleging that a woman from a social welfare organisation had promised her money in lieu for making a rape allegation against her employer. It wasn’t just the employer who was acquitted shortly after; the same year saw over three-quarters of the rape trials ending up in acquittals.

Another issue that Lahiri touches upon is that of classist contempt for maids. It was put on the display when a Meghalaya woman wearing traditional Khasi was driven out of the prestigious Golf Club House in Delhi for “resembling a maid”. Cases of reverse psychology (with the same classist contempt), where the employers decide against hiring a maid because she is pretty and not “maid-like” is another quintessential example of how we are always pulling at the wrong end of the stick. We just do not get it.