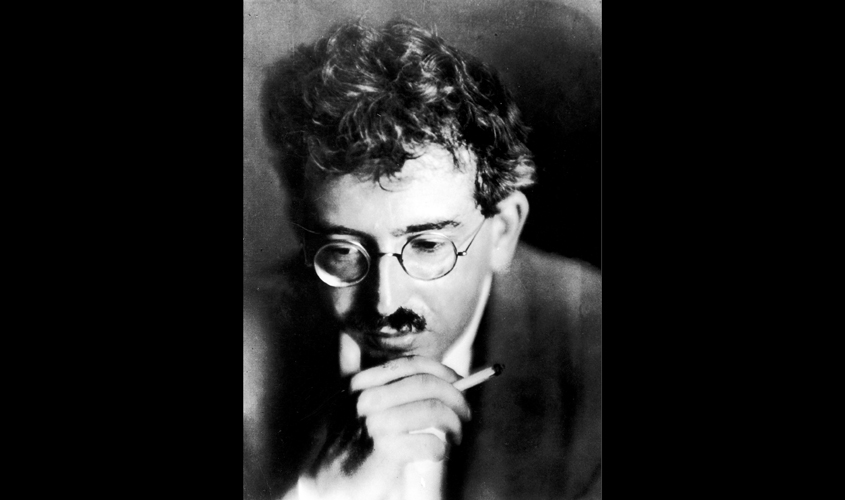

The question has been asked many times before: what would have happened had he managed to flee? Lutz Dammbeck, a German artist and filmmaker, imagines Benjamin reaching the United States “after an arduous journey through the Pyrenees” to become a part of Timothy Leary’s drug-use and psychology experiments at Harvard. Historian Norman Klein envisions Benjamin in Los Angeles as a connoisseur of Flash Gordon and detective novels. Esther Leslie, in her fabulous short biography of Benjamin, takes issue with such counterfactual narratives, while bestowing, half-seriously, yet more alternative lives on Benjamin: as a professor in Israel with his friend Gershom Scholem; as a fellow-traveller in communist Russia.

But my favourite alt-history scenario of this projected life comes from the essayist Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft, who, in a piece he wrote for the LA Review of Books in 2016, imagines Benjamin exiting Europe “via the unusual route of the British-controlled subcontinent”, and places him, for a brief transit, in Delhi.

Wurgaft here is motivated by Benjamin’s lifelong, and somewhat puzzling, interest in astrology. Since Delhi and Jaipur (the other city mentioned by Wurgaft) are both home to the Jantar Mantar—18th-century astronomical observatories set up with due regard for certain age-old astrological conventions—Benjamin would not have missed the opportunity to visit these cities. “He might have appreciated Jantar Mantar’s combination of astronomical and astrological devices,” Wurgaft writes.

But the very idea… Benjamin in Delhi! Let us for a moment forget the Jantar Mantar. What would Benjamin have made of the rest of the city: its divided nature, its class-, and in the colonial 1940s, racial-segmentation? What of its Mughal ruins? The “scraps of experience”—to use Benjamin’s phrase—picked up on its back streets? And yes, the bazaars of the Old Town, with their surrealist juxtaposition of useful and useless things, more colourful and “chaotic” than what Benjamin identified in the arcades of Paris as the symbol of modernity?

Would he have found the people here interesting? (“I am not interested in people,” Benjamin once said to Adorno, “I am interested only in things.”) The climate hospitable? (About a rain-drenched city in Europe, he once wrote: “This atmosphere militates against internal expansiveness.”) In historical fact, though, India never quite figured within Benjamin’s ambit of interests, or almost never. This I discovered only recently.

Among the German intellectuals of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Orient was a fashionable subject to engage with. And themes related to India were often explored. Either more directly, through language, as by Friedrich Schlegel in his comparative study of Sanskrit and Latin; or else tangentially, like Nietzsche’s philosophical adventures with Buddhist thought.

Among the German intellectuals of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Orient was a fashionable subject to engage with. And themes related to India were often explored. Either more directly, through language, as by Friedrich Schlegel in his comparative study of Sanskrit and Latin; or else tangentially, like Nietzsche’s philosophical adventures with Buddhist thought. The great German tradition of academic indology, Max Müller onwards, became another channel of interaction between the two cultures. Such was the environment that facilitated the emergence of Tagore as a literary celebrity in Berlin before anywhere else in the world.

Yet Benjamin, it appears, was unimpressed by it all. A few weeks ago in Berlin, I made a short visit to the Walter Benjamin Archives, with the express objective of establishing some sort of link—however tenuous—between Benjamin and India. Why? On one level, it had to do with a kind of cheap, journalistic urge to find something “topical”. But I also had in mind more legitimate grounds for my inquiry, not as a journalist but as a reader. We want writers we love to tell us more about ourselves, and to give us new eyes to look at familiar sites. It was for this reason that Wurgaft’s idea, of sending Benjamin to Delhi, my hometown, had so excited me. And for this reason that I had been desperately combing through Benjamin’s published work for even a stray reference to India.

At the Archives, it didn’t take me long to think up the keyword. “Delhi”, I told the woman assisting me with the search engine, which would scan through everything Benjamin had ever written—from essays to letters to scribbles on restaurant bills and postcards. Predictably, there were zero results. Next, I decided to broaden the scope, and searched for “India”, along with the German term, “Indien”. Again nothing. How about the adjective, “Indian”? “Indische” or “Indischen” in German. “Just search for ‘ind…’,” the woman said.

And there it was: Benjamin’s squib of a review, of a book entitled Heilige Statten Indiens (Holy Places of India), by Helmuth von Glasenapp. “This majestic work is a kind of critical catalogue on the temples of India,” Benjamin writes. “It divides into three parts: holy sanctuaries of the Hindus, the Jains and the Buddhists. The author has long been known as an authority in the area of the history of Indian religions. The selection and the quality of the large pictures reproduced here are of the highest order. W.B.”

These 65 words (in the original German, the word count is 46) —Benjamin’s only recorded piece on the subject of India—are part of a larger review of “three travel books”, published in 1928. I have dared to translate these into English myself mainly because there is nothing much to translate here, except for a set of four uninspired sentences, which together make perhaps the dullest paragraph Benjamin ever composed.

I read it out to Andreas Fanizadeh, the books editor with Die Tageszeitung, a Berlin-based newspaper. “Yes,” he said. “It certainly isn’t the best thing he ever wrote.” Possibly, this was one of those hack reviews that Benjamin was condemned to write, every once in a while, for money (penury recurred as a leitmotif throughout the span of Benjamin’s short life). But why nary a word from him, except for these 46, on all matters Indian? Why nothing on the Empire, nothing on Sanskrit, nothing on Tagore? And this despite his interest in astrology, in temple architecture, in cosmopolitanism. It’s possible that Benjamin found Oriental scholarship, and its patronising tone, averse to his taste. Or could it be that he was too involved with his other preoccupations to pay any attention elsewhere? Andreas gave me a more plausible explanation. “Maybe,” Andreas said, “if Benjamin had more time, he would have got around to this subject. But, you see, he died too soon.”