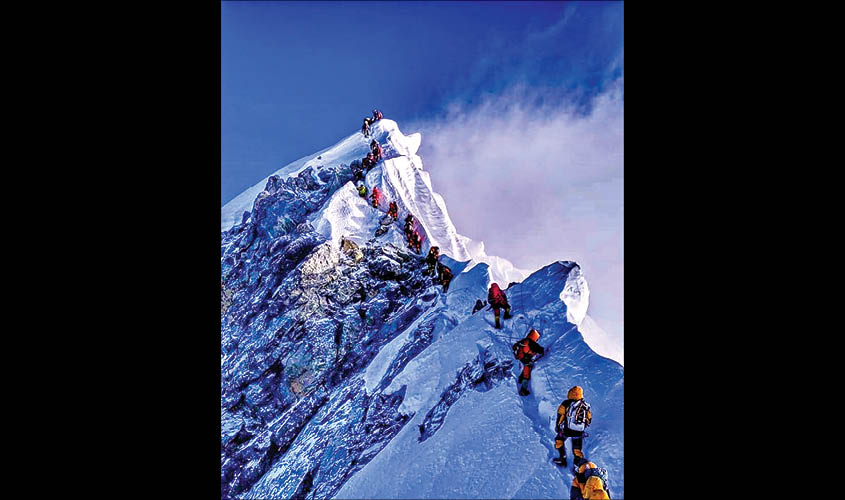

The unprecedented ‘human traffic jam’ near the summit of Mount Everest has claimed more than 11 lives and left dozens of climbers grievously ill. How did the highest point on Earth become an overcrowded disaster site? Rishita Roy Chowdhury reports.

There’s something surreal about all those images of climbers queuing to get to the summit of Mount Everest. The highest point on Earth looks like a popular tourist destination. It’s an awe-inspiring scene, and at the same time, it is the very picture of banality, for nothing is more banal than a bunch of people waiting in a queue.

As it appears in these photos, the Everest summit has become the site of a man-made disaster. It is the setting of a human traffic jam, which, in recent weeks, has taken its deadly toll on climbers. Around 11 people have died in the month of May alone because of overcrowding at the summit, while eight more still remain missing at the time of writing this story. Three among the dead were Indians. The causes of death in all these cases were linked to physical exhaustion and overexposure to extreme weather. In other words, the climbers died because they had to wait too long to get to the top.

The month of May offers a weather window suitable for climbing Mount Everest, when temperatures are relatively warmer and jet streams move away from the mountain. So there was no reason for this ideal season for summiting Everest to turn fatal. Except that too many climbers had applied for permits around the same time, and too many of them were allowed to go ahead without the possibility of overcrowding being taken into account.

Some expedition companies and veteran mountaineers have blamed these deaths on the growing number of inexperienced climbers on Mount Everest. As a consequence, even veteran climbers are forced to slow down and spend more time exposed to the harsh weather conditions. This can be particularly dangerous if you’re in the “Death Zone”, mountaineering slang referring to the region that begins at 8,000 feet and extends up to the summit of Mount Everest. Even without the overcrowding, the Death Zone had claimed many lives.

Ameesha Chauhan, a 29-year-old mountaineer from Dehradun, was witness to the human traffic jam at the summit this season. On 23 May, when she was descending from the summit, she had before her eyes a scene she couldn’t believe. There were climbers coming up the ridge and blocking the only route she had to take to return to base. “There was a lot of traffic and I couldn’t move. The situation was bad when I was on my way up as well, but the descent was difficult as there is a single fixed rope and I got stuck for 15-20 minutes. My oxygen was also running low and the queue was moving really slowly,” Chauhan told Guardian 20.

Since her return to Delhi, she has been in a hospital recovering from frostbite. “If there hadn’t been a traffic jam, I might have descended sooner and this frostbite would have never happened. Now I don’t know what will happen to me,” she said.

There are two routes that mountaineers take for climbing Mount Everest. One leads from Nepal and the other from Tibet. The Nepal route is more popular among climbers mainly because the approach from this side is comparatively easier, but also because Tibet has stricter regulations for climbers. This year, the Nepal government issued a record number of permits: 381, dozens more than the 346 permits issued last year.

Malay Mukherjee, a veteran mountaineer, believes that the onus is now on the Nepal government to implement laws to control the crowd on Mount Everest. “In 2017, the Nepal government was supposed to pass a law under which permits would be issued only to those with the experience of climbing at least two 6,000-metre and one 7,000-metre mountains. But that didn’t happen,” Mukherjee said. According to recent newspaper reports, the Nepal government might soon implement such a law or a stricter regulatory framework.

It costs tens of thousands of dollars to lead an expedition to the Everest summit, and $11,000 for the permit alone. With this kind of money involved, there’s a tendency on the part of expedition companies and government authorities to rubberstamp applications without properly vetting the applicants. This leaves the door open for inexperienced climbers, as well as for medically unfit ones. Since every climber on Mount Everest has to be accompanied by at least one Sherpa guide—some even choose to take along two or more—it further adds to the human traffic.

But there is another reason for this sudden spike in the number of climbers this year: the jet stream hovering around the summit. Jet streams are strong winds that travel across the upper layers of the atmosphere in narrow bands. When a jet stream is parked there, the Everest summit becomes absolutely inaccessible. Last month, when the teams of climbers began moving, they did so against the clock of an impending jet stream blast at the summit. As a result, there were more simultaneous expeditions to the summit than was safe.

Overcrowding on Mount Everest, however, is by no means a recent phenomenon. Satyarup Siddhanta, a Guinness World Records title holder for being the youngest mountaineer to climb the Seven Summits as well as the Seven Volcanic Summits, told us how the situation on the way to the Everest summit began to worsen a couple of decades ago.

He said, “It started happening with the commercialisation of Everest in the mid-’90s. If less experienced or fatigued climbers take more time to cross the bottlenecks near the summit, everyone waiting there suffers. Imagine if every climber takes five minutes to cross, and there are 20 climbers in the queue—that means a 100-minute wait for the 20th climber. Waiting at that altitude for around two hours often leads to hypothermia, frostbite and the depletion of available oxygen. This poses serious risks to even those who are fit and experienced.”

Rohtash Khileri, the 22-year-old from Haryana who summitted Mount Everest last year, wanted to achieve the world record of staying on the summit for 24 hours this year. But reports of overcrowding made him cancel his expedition. “It is very disturbing for me that I had to cancel my mission and did not go back to the final summit due to overcrowding. But I believe, the changing climate on Mount Everest has also contributed to the deaths this season. Increasing pollution and global warming can take the form of a natural disaster on mountain. We need to respect Mount Everest,” said Khileri, who wishes to accomplish this mission next year.

In a recent two-month-long clean-up drive led by the Nepal government, some 11,000kg of garbage, including oxygen cylinders, batteries, discarded equipment etc., were cleared from Mount Everest. Four corpses were also recovered in this drive, which ended on 5 June.

Since the first recorded successful summiting of Mount Everest by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay 66 years ago, more than 4,800 people have achieved this feat, and about 300 are believed to have died on the mountain. There used to be a time when only serious mountaineers dared to even contemplate such a climb. But today, Mount Everest figures on the global map of adventure tourism. If you have the cash to spare, you can choose your own Everest experience from an available range of packages.

This is part of the problem and it can only be addressed if government authorities in Nepal and indeed expedition agencies enforce a rigorous regulation and screening programme for applicants. And if climbers themselves learn to respect the mountain.