Leaders don’t follow trends. Instead, they do things that seem inexplicable or downright crazy. However, time proves them to be trendsetters. Way back in the 1970s, Dr Subramanian Swamy understood the worth of India’s northern neighbour, China. For the Nehruvians, China was the nation that had betrayed him. For the rest, except for diplomats, China was simply a vaguely threatening presence.

In 1981, as a result of his personal meeting with the Chinese leader Deng Xiao Ping, Dr Swamy had the route to Kailash Manasarovar reopened for the first time after the 1962 war. Dr Swamy was one of the first pilgrims to take this route as early as September 1981. His account of that trip reads like that of a Wild West classic of the late 19th century. This one is the story of Dr Swamy’s trip to Kailash Manasarovar in June 2016.

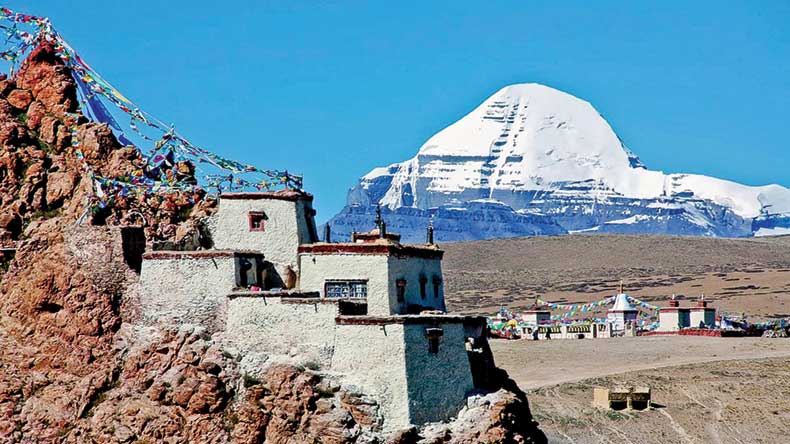

Shiva was a non conformist God and fittingly, at the holiest of His places, there is just the rock crowned by snow. The wind, sunlight, rain, huge mountains [of which Kailash is a part of, though by no means the biggest] and the tremendous sense of space make Shiva, Pancha Bhootha Natha—Lord of the Five Elements. There is no temple to Shiva at Kailash Manasarovar. Given the sheer grandeur of the place, there was no need for anything other than the mountain to imagine what was the best in each of us.

Dr Swamy and his delegation consisted of Jagdish Shetty, who had been mentored by Swamy since his teens and is now in his 50s, M.D. Nalapat, editor turned academic, and me. With characteristic Sinic courtesy, the trip started with a lunch hosted for us by the Chinese Consul General in Mumbai. Nalapat had gone to Taiwan for the swearing in of President Dr Tsai and could not come for the meal. Neatly typed out sheets of paper contained our detailed programme. Everything was written out and there was no space for error.

Starting with that delicious vegetarian lunch, we were on a high. Ancient Indian texts state that the Goddess at Kanya Kumari corresponded to the base, or the moolaadhaara chakra of Kundalini, reaching out to Kailash, which was the Sahasrara or the thousand-petalled lotus. We went to Kanya Kumari to get Her blessings before the trip.

The night flight from Delhi to Beijing was uneventful but for the warnings of well wishers about my state of health. Rough and contrarian genes from my father made us both very unpopular with the wellness industry. If there was any way that I could manage to go to a toilet by car, I would have, so unpopular was exercise to me. Dedicated smoking [quit since 30 years] had left its tar printed on my lungs too. Mind over matter, mind over matter, I muttered myself to sleep.

At the Beijing hotel, a hectic round of meetings was lined up by the hard-working Chinese. Taking into account Dr Swamy’s fondness for an afternoon nap, this was a “light” schedule. Our hosts took us for a classical opera about the sixth Dalai Lama. The next day’s visit to the China Tibetology Research Centre [CTRC] with an attached museum was delightful. There was the model of the railway we were to take to Lhasa in a couple of days. The CTRC has links with 22 countries, but not with India. Chakreshwara, Tara, Avalokiteshwara, the familiar names slid off my tongue.

The vice president of the organisation hosted us for dinner. He was laughingly accusing his colleagues of never accompanying him to Kailash. We heard horror stories of people from India who went up to Lhasa and could not proceed further because of high altitude sickness. Suddenly, what I had searched on so diligently on the Internet became real. “Shankara, make us see Kailash,” I sent a fervent plea. The quietly efficient Jagdish Shetty had carried enough high altitude medicines for all of us, something that was to save my life many times over.

Our friend Sony Badiga had us over in his and his Chinese wife’s beautifully preserved heritage home for coffee and wine. A teetotaller, Swamy frowned at me. “You are on a pilgrimage, madam.” I reminded him how Shiva’s wife was described as “Mahaa Paana Madonmaththa [She who is drunk on Vaaruni, the wine Divinity’s gift]”.

Apart from the irrepressible Einar Tangen’s company, Sony gave Nalapat a wonderful pair of hiking boots on seeing with some dismay his everyday shoes. I had absolute faith in my sturdy Nike.

We flew to Xining, which is about 7,500 feet above sea level. All the members of the journey had gathered there. There was Peng Keyu, retired ambassador, Wu Wei and Han Hongcai both from Beijing and Yang Yong from the Chinese Consulate in Mumbai. We were to be together for the rest of the journey.

A visit to the Ta’er Lamasery showed that while China did not officially revere religion, the Lamasery was a thriving centre of Buddhism. There was a corridor full of thick yoga mats, what a Keralite would call “kosadi” and there were groups of people genuflecting continuously. These were those pilgrims who would circumambulate Kailash in what is called a namaskara parikrama. Four to five years is the time taken for training for this Herculean task of devotion and there were both men and women oblivious to all but the bend-pray-rise-pray sequence. Quickly, I patted my knees—their daily job was to hold me up without complaint. Rather unconvincingly even to myself I scored emotional brownie points by telling them that I would never put them through that.

After 23 hours we pulled into Lhasa station. There was the Mayor, his colleagues and a doctor to check on our health. Despite our rather queasy state, the doctor was satisfied. We met the charming interpreter Dawa Yuzhen, whose sweetness concealed clockwork capability.

The hour long walk on an incline at that height at the Ta’er Lamasery made Jagdish and I [who were most unlike the health conscious Swamy and Nalapat ] confident of our ability to huff and puff, but yet keep up.

Yang Li Mei was our host for lunch. She reeled off facts about Xining which made us want to return. India needs people like her—a one-woman tourism promotion agency. Post lunch we boarded the train that was to take us to Lhasa. The comfortable four sleeper compartment was shared by us, while the Chinese part of the delegation was next door. A lot of other foreigners were there too. This seemed to be the most popular way to reach Lhasa. The night was to teach me why.

With stars hanging like bulbs in the sky, we chugged our way up. At every station, Jagdish and I would jump out to assess the altitude and temperature. Convinced that we would be stranded on the platform ticketless, language-less and with inadequate warm clothes, Nalapat would herd us back into the compartment long before the train left. As is the wont in most train journeys, we turned in early. Our Chinese friends had told us that we would cross the highest point of this trip when we were on the train. “Don’t worry, we will all be asleep,” said Mr Yang. A bit of me wanted to be awake when we crossed nearly 22,000 feet. Less than a ten thousand feet to the top of the Everest, I thought.

Within seconds Swamy was fast asleep on one of the lower berths. He did not wake up even when Nalapat and Jagdish clambered up to the upper berths with difficulty and with giggles and suggestions from me. With the curtain open so that I could look at the stars I dozed off.

The train was heated and oxygen was being pumped in. Suddenly I woke and found that I had to sit up. There was something squeezing my head and breath. Slowly, slowly, breathe deeply. Art of Living, Lara, Manoharan… I ran the teachers through my mind and the fact that I was way behind in my practice. Swamy was sleeping. The others seemed to be so too. Was I the only one awake? So many people saying “I told you so” flitted through my mind. I should not have tried this. Shiva was everywhere. Why did I believe that He had to be visited in Kailash? Why, there was that cute little Shivalingam just behind Attingal Bhagavathy. The thought of Her, my beautiful Kali calmed me. Take control of my breath I told Her. And She did. She took charge. That was the last time I felt discomfort regarding my lungs, whatever the oxygen gauge showed later on.

The next morning we met for breakfast. We had before dawn crossed the Tangola pass between Tibet and Ali prefecture. This was the worst part of the journey and things would only get better. But for Swamy, the whole lot of us, Indian and Chinese, looked green-faced. My headache was intensifying and I dreaded throwing up in the bathroom. Nalapat, who hated sitting still, was chafing at the length of the train ride. Whenever Wifi was available on the train, again courtesy the resourceful Jagdish, Nalapat would chart out route after plane route to get to Lhasa. Wonderful hosts that the Chinese are, they would not have chosen this (going by train) method of travel, but for a very good reason, said Swamy: acclimatisation.

After 23 hours we pulled into Lhasa station. There was the Mayor, his colleagues and a doctor to check on our health. Despite our rather queasy state, the doctor was satisfied. We met the charming interpreter Dawa Yuzhen, whose sweetness concealed clockwork capability. We stayed in Lhasa for two days in the incongruously named St Regis hotel.

The next morning we went up to the Potala Palace. With its deep maroon [a local plant that holds together even in earthquakes, painted maroon as we discovered soon] and white facade rearing up into the sky, it looked magnificent. The Palace was 13 stories high. Even Nalapat, who was used to rigorous workouts, found the going tough. A portable oxygen canister, Chinese herbal tablets to increase intake of oxygen and a bottle of water was whipped out from the doctor’s bag. Taking in lungfuls of oxygen, I loved the mural paintings, the golden stupas, the mandalas in the palace. There were crowds of devotees going round turning prayer wheels, genuflecting, giving offerings of oil for the lamps and money. For them this was a sacred place of worship, more than a tourist attraction.

The view from the terrace was astounding. The ring of mountains around seemed to protect rather than restrict this town. Despite the huge steps [found in most ancient sites] the palace would have been wonderful to live in, with the smell of incense and soft whispers of prayers rather than the cold antiseptic air trapped in most museums.

Dawn of the next day saw us fly to Ngari Gunsa, one of the highest airports in the world. While circling down to land, a visibly excited Swamy pointed to the window. “That looks familiar,” he said. Nestled among the conveyor belt of snow peaks was Kailash. Was there a dancing couple there? And Ganesha? I strained my eyes. Shiva and Parvati were dancing in my heart.

There were two doctors with us equipped with oxygen canisters from then on. We drove to the foothills of Kailash where we were to stay. There were miles of road with solar panels directly connected to power grids throughout. Colourful Buddhist flags flew with only the wind to tend to them. Sheep and yak grazed peacefully on the coarse grass that grew in tufts. Suddenly in the midst of nowhere, our entourage came to a halt.

There in the horizon was that peak made familiar by the photographs that hung in my brother Adityan’s room, Swamy’s profile picture, shlokas recited by many elders. “Photo,” said our Chinese friends. For the sake of all who had told me to think of them, pray for them, I knelt on the road. One of my uncles who had passed on used to refer to himself as “GT Senior” and me “GT Junior”. GT stood for “Great Thiruvathira”, Shiva’s asterism. I shared my birth star with Shiva. “GT Original,” I whispered.

The next day we drove to Manasarovar. With endless blue waters, distant snow mountains and wilderness it looked like a world that had just come into being. One could smell the peace. Instinctively we lowered our voices so that the birds were the loudest.

After a quick lunch, we dressed for the minus-3 degree temperature. We were to go the point where we could view Kailash closer, as well as do the parikrama by car. Against a blue sky innocent of clouds the mountain seemed to have waited for us. Perhaps through births…

What each of us gave and took back from that mountain shall remain as much mentionless as the significance of that particular peak to so many. The Tibetans call it Snow Guru. The Hindus revere it as do the Buddhists. It is certainly not the tallest or the most beautiful. And yet indescribable.

There were people who opined that to get full benefit of the pilgrimage one has to suffer. When Shiva held a race between His sons Kartikeya and Ganesha as to who would circumambulate the universe thrice to win a mango as a gift, Kartikeya rode away swiftly on his peacock. Knowing that He could never catch up with His sibling, Ganesha went round Shiva and Parvati thrice. His explanation was that the universe was contained in them and there was nothing outside of them. Ganesha won the mango. With contours matching Ganesha, I assured the rest of the delegation that doing the parikrama by car would be objected to by human beings, not Shiva. There was a precedence to it, after all.

At the hotel the doctors stuck two prongs of the oxygen source into my nose. Ammumma [my grandmother] and Amma [my mother-in-law, Kamala Suraiyya] came to my thoughts. Both of them were no more, gone within a year of each other almost. We had all learned at their bedsides to be adept at reading oxygen levels. The Himalaya Hotel had Indian food as it was within the parikrama path.

The next day we drove to Manasarovar. With endless blue waters, distant snow mountains and wilderness it looked like a world that had just come into being. One could smell the peace. Instinctively we lowered our voices so that the birds were the loudest. Even the wind had died down leaving tiny waves on the lake. I had read about the pristine waters of Manasarovar and as it happens only rarely, reality did not disappoint. Even though I was desperate for a dip in the waters, the doctors forbade us in very clear terms.

Manasarovar exuded peace, a tiny bit of which we all carried away in our soul. We then drove to a point where we could see both Kailash and Manasarovar. An old man was there, tying up flag after flag around a Buddhist stupa in the evening sun. His prayers were added to those who had long gone before us and those who would come after us.

Silent, we drove back. There were too many myths, associations with that part of the earth to express in words. We were fortunate to have been able to be there. Turning back, I made a vow that I am still not sure to whom. I will return. Nalapat, Jagdish and Dawa Yuzhen looked quietly away when they saw me cry. I did not want to leave.

We arrived in Lhasa to light rain. It felt colder there than it had on the mountain. At Lhasa airport the next day the delegation was splitting up. We Indians were to go back to India via Nepal. Our Chinese hosts had thought of everything. The vegetarian food, the medical facilities and their sensitivity as non believers to our faith showed not just a job well done, but one done with care. China’s regard for old friend Swamy was evident at each step.

“You will return,” Ambassador Peng said, which was what I wanted to hear.

In Kathmandu, the suave and charming Ambassador Ranjit Rae gave us lunch. He spoke of the people who were stranded due to rains and of people who had disobeyed their guide and wandered off by themselves. A couple had died due to exposure in the high altitudes. For people for whom the sea was a scarce twenty-minute drive away, mountain sickness sounded like an old wives’ tale. With flawless manners the ambassador sent his team to see us off.

Jagdish had yet another flight to catch to Mumbai. I watched him rush off. With his packets of dried poha for snack, camphor for oxygen and endless bits and pieces of gadgets, Swamy was lucky to have him accompany his childhood into adulthood hero to most places.

Sorting through a huge pile of warm clothes, I told Nalapat, “When they called Swamy crazy for admiring China he stuck with his choice. Look at the result.” Even after Nixon had resigned as the President of the United States, Chairman Mao had sent him his personal plane for what was tantamount to a state visit. Personal friendships still have their place of honour in some cultures.

Thiruvathira Thirunal Lakshmi Bayi is a writer and poet