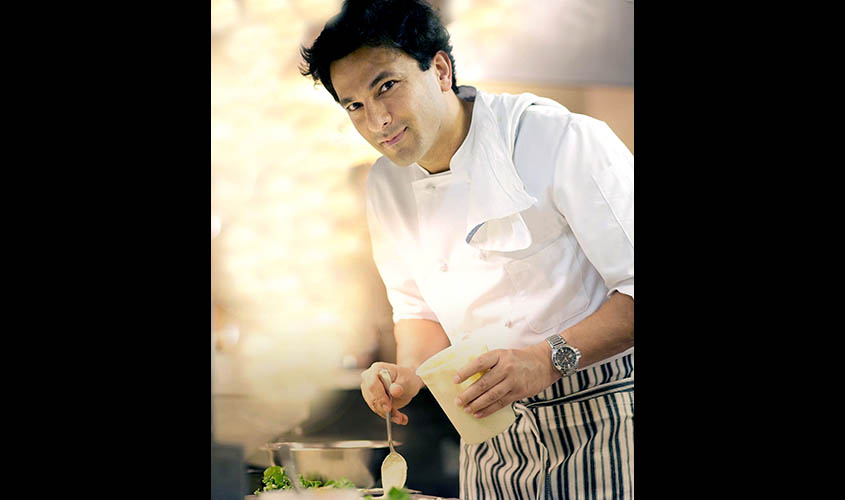

Michelin-starred chef Vikas Khanna speaks to Rishita Roy Chowdhury about how he went from heading a catering business in Amritsar to establishing his own restaurant in New York, why he wants to popularise Indian cuisine the world over, and what inspired him to make his debut film, The Last Colour, which is in the running for an Oscar nomination.

Q. Tell us about your journey in the culinary world.

A. I entered the industry for the survival of my family. I was 15-16 years old when I started catering and earned some money. I felt empowered, I felt alive. I thought I could help my parents by not just cooking but turning it into a business. So I found a small place and opened a banquet hall where I lived in Amritsar, but it didn’t work. Then my uncle saw my passion for cooking and advised me to get formal education in the culinary arts. But I didn’t get support from my family. They dismissed the idea by saying, “Hamara ladka bawarchi banega[Our son will become a chef]?” They were thinking of financial security. No one knew who chefs were or what they earned. It was a very close-minded thing. I still remember an aunty had said that cooking wouldn’t get my face on Forbes, but it did. Everyone had cut me off at that time. Even my mom said that I would end up being a waiter. Awareness wasn’t there. But then I got my degrees and worked at the Taj, Oberoi, Leela and several other five-star hotels before finally landing in America. That is where things changed.

Q. What fascinates you about the art of cooking?

A. From the farms to the stores and kitchens to the dining table, the journey of food is amazing. I feel a sacred equation with cooking. I knew I had to stick to this. Food erases all the borders. It is the soft power of India. One can melt hearts with our beautiful dishes. When people eat Indian food in foreign countries, aren’t they being introduced to your culture through food? We show the diversity of our country through food. The flavours and dishes do the talking.

Q. You have cooked for such public figures as Barrack Obama, Dalai Lama, Pope Francis and Queen Elizabeth II among others. What kind of challenges have you faced in establishing yourself on the global stage?

A. These experiences have been really humbling. But there have been many struggles along the way. I recently found a letter I had written to my grandmother in 2001 when I was in New York. I wrote, “Your prince is a slave now; maybe I was never a prince.” It’s because I used to work small jobs. Then there were people who thought dark-skinned people can’t cook. Actually, where there is art, there’ll always be predators, who would want to snatch away at everything and won’t ever leave you in peace. They will come at any level, in any form. From a small place I reached New York, won a Michelin star and became part of so many great cooking projects.

Sometimes I doubt myself. My backing has always been zero. But people like me can never settle down. I wasn’t happy working at five-star hotels. I wanted to put my own expression and vision out there. People keep asking me to stop. But from where I come, very few people get such a big platform. Every time Gordon Ramsay meets me, he would say, “You always surprise me with whatever you do and you try to do every project with such high international quality.” Honestly, I don’t have a personal life, so this helps me to constantly keep moving. It’s a reminder in so many ways that we are capable of doing anything we wish to do.

Q. What has been the highlight of your career until now?

A. For me, it’ll always be the Michelin star. I remember, in 2008 I was working at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Paris. It was a very difficult time when I realised how inferior I was considered. I was dark and they would not let me touch the food. They thought dark people can’t cook. One day I made a dish for the chef I really used to respect and love, and he said, “Tell that dark s*** I will never eat anything from his dark hands.” That was enough for me to wake up and say the next time I come to your country, I will not be a chef or Vikas; I will be the Michelin-starred Chef Vikas Khanna.

It wasn’t normal in our culture to aim for the Michelin star. It was a huge struggle to achieve it. They didn’t consider I could cook and that was enough for me to change their perspective. People always consider winning something as the highlight of their careers. For me, it was when I lost my dignity. I left that job and carved my own path. But I feel if you don’t get pushed to that point, you wouldn’t know your strengths. Just don’t let anyone define your space. I don’t let anyone tell me what I should do. I am going to be the person with a free-flowing spirit—a person who is always creating something he believes in.

Q. Tell us about your recent foray into filmmaking and your directorial debut, The Last Colour. How did the project come about?

A. I was in Varanasi and saw people preying on women and children in the name of faith. Colour is a symbolic thing in the film. In spring, flowers blossom and we celebrate Holi. But there I saw the dark side of our society. Then I also went to Vrindavan and was shocked to see that the widows weren’t playing Holi. I wrote a short story on the subject but no one published it. Then I also left it under the carpet as so much was going on in my life. Later, in 2013, these widows played Holi for the first time after a Supreme Court’s order broke their shackles. I also met a ropewalker who wanted to join the police force to teach the corrupt ones a lesson. I felt the universe was telling me a story but I wasn’t listening. So I went to Bombay with the screenplay of this original story and everyone refused to take it up. They said a story about a widow and an untouchable child won’t ever see the light of day.

I might be the only Michelin-starred chef whose movie is in the running for Oscars 2020 nominations [The Last Colour has been announced as eligible for nomination in the Best Picture category]… This is a very difficult space to enter for a chef because you also get criticised a lot. People think I am not focused, but that’s not the reality. If I hear a story I think it’s my responsibility to bring it to the masses. When the film was announced, I got criticised a lot. They said, “You are not a filmmaker, why would you make a movie? This is going to be a failure.” But this story needed to be told…

Q. You are also one of the judges on MasterChef India. How is that coming along?

A. I am loving it. It’s such a revolution in India’s culinary history. People thought we are less than international chefs. But we have not one, but two Michelin-starred chefs on the panel. This is simply amazing. The show is also introducing me to aspiring chefs. For me, it helps to reach millions in one day. The reach we have because of the show is unimaginable.

Q. You are known for transforming classical recipes into contemporary dishes which appeal to diverse palates. When did you start experimenting with Indian cuisine?

A. I have been doing it for 10 years. This is my way of doing justice to our wonderful cuisines. Normal or typical food doesn’t draw the price points and appeal. People think there is no imagination [in it]. I want people to see Indian food and Indian chefs as creative. I was thrown out of my job because I was dark, so I am very driven when it comes to popularising Indian cuisine.