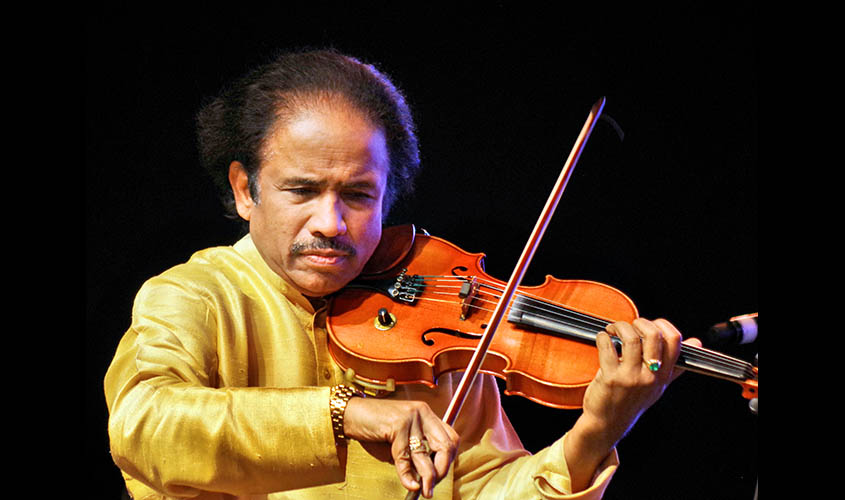

Carnatic musician and violin virtuoso L. Subramaniam has performed concerts around the world and has collaborated with some of the biggest names in both Indian and Western classical music. He speaks to Rishita Roy Chowdhury about how he got the violin recognised as a solo instrument in Carnatic music, and why he thinks traditionally-minded musicians in India need to innovate more and evolve with the times.

Q. You organise the Lakshminarayana Global Music Festival annually to celebrate the musical legacy of your father, V. Lakshminarayana Iyer. Tell us about your classical music training under his tutelage.

A. My father wanted to establish the violin as a solo instrument in the international scene, because during his time, violin was an accompaniment. He created a lot of new techniques for the violin to make it globally acceptable. Westerners thought our music was only ethnic or folk, in which we sit on the floor and play. That was the kind of impression they had. So my father’s dream was to make the Indian violin acceptable and heard in the greatest concert halls. Looking at him play, I was fascinated and wanted to become a violinist. But my elder brother was already doing it, so I was advised to sing. My father started to teach me vocals initially, but then, when I was two years old, I was diagnosed with diphtheria and doctors said I might lose my voice later on. I had to then learn some instrument and finally I got to learn my favourite, the violin. In 1958, we came back to India from Colombo because of the riots in Jaffna. But my training continued. I was very happy.

Q. You became popular as a child prodigy when you made your live performance debut at the age of six. Tell us about your journey as a violinist.

A. When I was six years old, my father wanted me to perform at a temple during a big festival. He was also playing there and suddenly announced that I would make my debut. Since I was very small, the organisers were sceptical, especially because there were thousands of people in the audience. They said, “He is very young, so maybe he can play in the future, but not at this festival.” They didn’t want me to play. But my father had to go through with his plan as he wanted me to start playing on that auspicious day. I vaguely remember that situation because I knew the organisers didn’t want me to play and my father did, and in between there was a huge gathering. It was my first concert, so I was worried. But the organisers praised me after the performance and people were happy. My career started in a temple with a solo piece. Then slowly, I started playing with my elder brother and with my father. But education, too, was important and I was interested in science, so I went to medical college.

During my second year at Madras Medical College, my father asked me to play for a German violinist who had heard me play with my father and thought I had the potential of becoming a great artist. He wanted to coach me to help me become an international artist. I was very happy, but I had to finish my degree in medicine. At the time I was depressed and nothing worked. I tried my best to leave, but couldn’t. Then, after my studies, I applied for scholarships for a master›s course. It was a blessing that my mother made me finish the undergraduate course, otherwise I wouldn’t have received my certificates later on.

Q. You are known for having taken forward the legacy of your father and contributed to establishing the violin as a solo instrument in Carnatic music. What motivated you to achieve that?

A. The violin was a permanent accompanying instrument at concerts in the old days. There was no opportunity to play solo. No one could make that demand. It was uncommon. Violinists had to accompany other musicians to survive. If you performed well and got good a response from the audience, you wouldn’t be called for the next concert. They wanted the violin to be a background thing—an instrument that does not get attention. So violin techniques were not developed too much because they were not needed. An average bachelor’s student played with a better technique than established musicians as the violent wasn’t important in India back then.

So my father realised that the problem was that the same techniques were being applied by both accompanists and soloists. That is why the Indian violin didn’t get quit appeal to Western audiences, who have had a violin tradition for a much longer time. Our violin music was interpreted as typical ethnic-folk. This pushed my father to change the scenario and bring in new techniques.

I, too, started developing his dream and tried taking forward whatever he was doing. Soon, the Westerners got fascinated and I got invitations to play with some of the greatest violinists and orchestras. My music was accepted because of the technical changes it incorporated. It also encourages the next generations to take up the violin as a solo instrument.

Q. You have been a part of many cross-cultural collaborations involving musicians from the Carnatic and Western classical schools. Are there any parallels between the two styles? And what are the differences?

A. The very basic thing is that Western music is about standing up and playing; in India, we sit down and do it. The tuning is also completely different. Moreover, musicality and ornamentation vary as well. In Carnatic music, we try to convey emotions in ragas through ornamentation. In contrast to that, Western music is characterised by harmony. They have notes and scales which create different tonalities. Rhythms and structures are also followed differently in the two forms. They don’t take the compositions and play them at multiple speeds. These are the strengths of our music. Western musicians are into fixed notations written by great composers. Each composition written for a particular instrument is played on that instrument only. For us, it’s flexible. We can also experiment with the pitch, which they can’t.

Q. To what extent has Carnatic music influenced Hindi film music?

A. Earlier, we had composers who created raga-based compositions. The scene was similar in north India as well. That approach spread and it was copied, adapted into every other language. Some solid Carnatic classical singers received a lot of attention in Indian film music. Carnatic music has had a great influence all across India.

Q. Having learned classical music since childhood, did you ever have inhibitions about incorporating other styles into your performances? What are your thoughts on fusion music?

A. Some of the greatest artists from the south adopted or incorporated ragas from the north, and northern musicians adopted Carnatic music. There was a mutual exchange of ideas.

Increasing creativity brought more prominence to music in India. If we have the exact same music that we had 100 years ago, no one is going to listen to it. Every one of us creates their own interpretation, add their own flavours, their own colour and try to reach the masses through their music. Even if you get adapted or exposed to one particular style, I believe one should not have a closed mind. Without collaborative work, Carnatic music couldn’t have gone to the level of international acceptance it has now. Without innovation, you become stagnant. Our music would have disappeared without the variety of things that have happened and are still happening to it.

Music has no language barrier. It’s important to notice what is happening around the world to be more creative and innovative. The ultimate aim for an artist like me is to take our music to the global platform and gain acceptance, by reaching millions of people. Talking about innovation, Ali Akbar Khan Sahab and I were the first two to perform a north-south jugalbandi. The audiences appreciated and understood the experiment. Collaborations widen the scope of music in India as well as on the international stage.

L. Subramaniam will be performing, with several other musicians, at Delhi’s Sirifort Auditorium on 4 January 2020 as part of the Lakshminarayana Global Music Festival