Hashiya: The Margin, a group show that opened recently in Delhi, explores the old 15th-century idea that in painting, what lies in the margins can be as valuable as the centrepiece. Bhumika Popli speaks to the show’s curator and participating artists.

A new art exhibition at Bikaner House, Delhi, takes our focus away from the centre and curiously, shifts it to the margins. The show is aptly titled Hashiya, which is the Persian word for “margin”. Painters in 15th-century India, Persia and Turkey were among the first to seriously think about utilising not just the centre of the frame but also the space around it for their art. During this period, when muraqqas or scrapbooks were used to gather calligraphic samples and miniature paintings, there emerged a huge scope for artists who were employed to assemble the scrapbooks. The borders had caught the attention of these artists, who then began decorating the margins.

In an essay by Kavita Singh, “Hashiya: A Margin, A Border, A Frame”, Singh states, “They [the artists] started by filling it with scrollwork, flowers and arabesques. But soon, they became aware of the narrative possibilities of the hashiya, where margins could “speak” to each other across the turn of the page. Thus, as little birds fluttered across the patterned field, the alert reader might see a bird pursue a butterfly on one page, only to catch it in the next. Around a painting of a mehfil where poets tried to outdo each other with their fine words, there might be marginal decoration that showed simurghs (Persian mythical flying creatures) and dragons in furious combats.”

The ten artists, included in the show organised by Delhi’s Anant Art Gallery, have attempted to revive the old tradition of illustrated margins in miniature paintings in the context of the contemporary, and have rendered multiple narratives for the viewers through paintings and installations.

One of the participants in the show, the acclaimed artist Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, through his watercolour painting Majnun in the Margin, takes our attention back to a painting created circa 1640-1650. That painting, titled Majnun in the Wilderness, forms a part of an album assembled for the late Shah Jahan, the Mughal emperor. “Hashiya is a fascinating, tantalising, intimidating idea,” Sheikh says. “Much of what we need to engage with these days has been pushed into the margins: conservation and the love of nature, the green cover of our forests, besides the struggle for free speech and right to dissent. It is not unusual to find artists alongside vegetation and fabulous animals in the margins of Mughal folios. Kavita Singh in her essay ‘Hashiya’ has reproduced a painting of a disconsolate Majnun in the central space while Laila seated in a litter upon her camel is put in the margin. In his eternal quest for Laila, my Majnun has moved into the margin, but where is Laila?”

In his own painting, Sheikh has drawn two skin-and-bones Majnus near the edges of the canvas. And his centrepiece comprises elements that can be seen to be entirely incidental to the painting: sketches that resemble an urban landscape.

The curator of the show and the founder-director of Anant Art Gallery, Mamta Singhania speaks to Guardian 20 on her fascination with miniatures. “I have worked extensively with artists who are inspired by miniature paintings. Among the different concepts, I once looked at the artistic response to an age-old concept called ‘seasons’ or ‘ritu’. Recently, when I was relooking and revisiting the miniature paintings, I found that hashiya was never explored in the contemporary context. The idea of the show emerged from there. For me, margins are not just about outside the central painting or let’s say the central image, it could also be interpreted by the artists in different forms, and they can explore the concept by their own different ways. Hashiya existed in miniature as a decorative aspect so you have a decorative border around a central image, then it slowly started took a different aspect during Mughal paintings as more emphasis was added to the margins. It took a more important role. My whole purpose was to explore the concept of the hashiya via artistic responses of these contemporary artists.”

Desmond Lazaro was born in Leeds, England, and now lives in Pondicherry. Migration is one of the principal themes of his art. He is inspired by the Dymaxion map created by Buckminster Fuller in 1943. Devika Singh, curator of Dhaka Art Summit, 2018, said in a statement, “Fuller’s map is based on a mental construction of an alternative comprehension of the world, which abandons the Mercator projection and its use of the equator as the reference line. Its aim is to minimise the distortions of conventional representations of the earth and their embedded cultural biases. Lazaro transcribes onto the icosahedron his family’s migration route in the 1950’s from Burma to the United Kingdom and set it against the great maritime voyages of Vasco da Gama, Cristoforo Colombo, Fernao de Magalhaes and James Cook—explorers who, followed their Arab, African and predecessors, instigated modern global trade.” Fuller was originally invited to give a Nehru lecture in Delhi in 1964, in which offered a vision of what India could be in the future and how South East Asia could respond to the post-colonial phase of its history.”

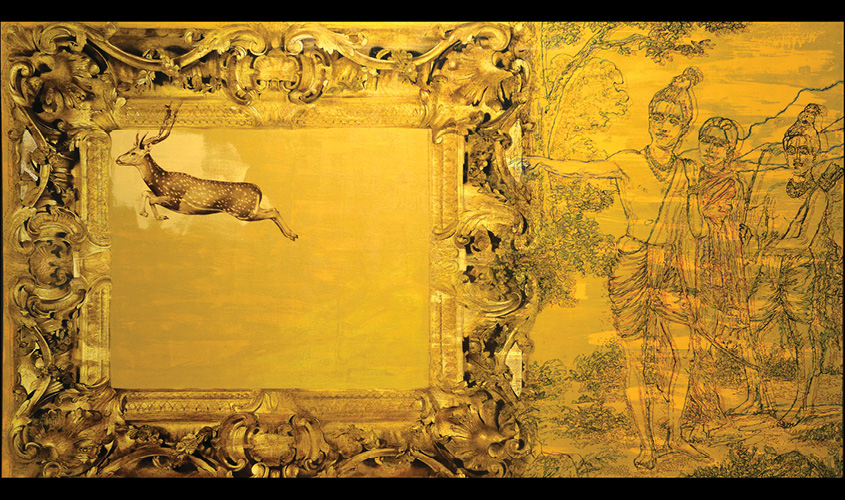

Artist V. Ramesh, who is also a part of the Delhi exhibition, thinks that hashiyas are not really taken seriously by today’s painters. He says, “It is assumed that they are significant enough.” In his oil painting, titled This or That: Regarding a Golden Deer, he goes to the incident which led to the kidnapping of Sita in the religious text Ramayana.

The golden deer is seen leaping in the main frame and on the border of the canvas we see Sita, Rama and Laxman. According to the artist, “On a superficial level, we can say that a demon came in the form of golden deer. But in the back of my mind, I thought, all of us hanker, crave about the things which are actually not really necessary to our lives, just like a golden deer…”

Hashiya: The Margin is on view at Bikaner House, Delhi till 24 April