Few writers in Indian history have recorded the lived reality of Partition in such detail as Fikr Taunsvi, writes Maaz Bin Bilal, the translator of Taunsvi’s newly published Partition journal.

The Sixth River is the journal of Fikr Taunsvi, the immensely popular and critically-noted Urdu satirist and columnist, from the time of the Partition of India. It is his eyewitness account of the sundering of the Punjab, while living in Lahore from August to November 1947 until he migrates to Amritsar in postcolonial India, leaving behind his beloved city in the newly created Pakistan. Fikr feels passionately about and reflects deeply upon the tragic political and social events, giving us a journal which becomes a Partition text like no other. Here, a poet and literary writer comments on the trauma of the migration and violence, and the politics that allowed it, through dark satire and irony, but also from personal experience as an eventual migrant and refugee. In The Sixth River, Fikr stands out as an inimitable descriptor and thinker for what he describes of Partition-related events, the violence and politics, as well as the lives of other notable intellectuals and artists, and presents it all in his evocatively harrowing, self-deprecating, deeply ironic and reflective prose.

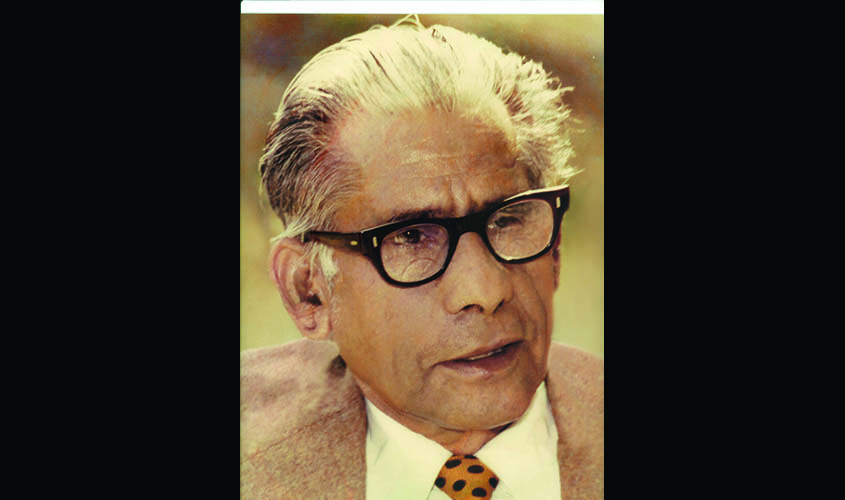

Fikr Taunsvi (7 October 1918–12 September 1987), born Ram Lal Bhatia, abjured his given name, calling it “vahyaaat” or “absurd” or even “fake” and preferred to be known and addressed by his takhallus or pen name. Fikr from Urdu can variously mean: thought, consideration, reflection; deliberation, opinion, notion, idea, imagination, conceit; counsel, advice; care, concern, solicitude, anxiety, grief, sorrow. Taunsvi implies “hailing from Taunsa Sharif”, a city in the Dera Ghazi Khan Tehsil of western Punjab that now lies in Pakistan. The city is noted for its numerous Sufi shrines. Fikr hailed the shrine of Khwaja Sulaiman Rasul in particular, which was patronised by both Hindus and Muslims. Taken together, the two epithets form a pen name that best describes Fikr’s personality, aspirations and concerns. A deep and sensitive thinker, he engaged strongly with and reflected closely upon life and the human condition, as someone who engaged in fikr or may even be considered a fakir in the truest sense of the word. His cultural identity as a Punjabi with his roots in the composite Sufi culture of Taunsa Sharif shaped his pluralistic worldview. His humble origin from a small town and growing up with poor parents also meant (as he recognised himself) that he wrote for them, or the poor. This is amply reflected in Fikr’s work.

By Fikr Taunsvi

Speaking Tiger

Pages: 184

Price: Rs 499

Fikr, the thinker, is also self-critical enough to admit that his father was a wily shopkeeper and businessman, who sold to and cheated Baluch tribal customers at the edge of Taunsa Sharif, which he claims lay at the western edge of colonial India. Due to moral indignation against his father’s corrupt practices and “exploitation” of the tribals, and his refusal to provide for his further studies, Fikr left home in 1934 after high school. He wandered across the Punjab, moving through Dera Ghazi Khan, Jampur, Multan, Lyallpur and Sheikhupura, before settling in Lahore, where he found employment eventually with editorial offices of newspapers and started to practice writing seriously. It was also in Lahore that he found the culture that he had yearned for, but could have never acquired in the peripheral town of Taunsa.

Fikr started off as a poet in Lahore, publishing his first poem in the newspaper Adabi Duniya and subsequently his poem “Tanhai” in the annual anthology published by the Modernist group, Halqa Arbab-e-Zauq. He also found work first as a clerk then as an editor at Adab-e-Lateef, and later at Savera, which he edited with his friend, the short-story writer, Mumtaz Mufti. Fikr has described Savera as a Progressive or socialist-leaning magazine, while Adab-e-Lateef too started off in this manner, but soon turned more Modernist. Thus, Fikr had occasion to absorb the two key strands of art and creative writing dominant in the subcontinent at the time. This also explains his intellectual agility and deep sensitivity to both craft and human issues. Fikr also continued to educate himself by frequenting the Maktaba in Lahore where leading Progressives such as Rajinder Singh Bedi, Ismat Chughtai and Saadat Hasan Manto used to visit.

Fikr’s first poetry collection Hayule (shadowy forms, apparitions) was published from Lahore too, in 1947, during the tumultuous events of Partition, and he laments the book being left behind in Pakistan. Lahore for him, as one reads in The Sixth River too, became the city of (composite) culture and the arts, intellectual inquiry, and creative and professional opportunity. But perhaps even more strongly, Lahore for Fikr was the place of friends, of his genteel society, camaraderie and social etiquette. This love for Lahore and all the values it stood for was the reason the Partition hit him even harder.

The experience of Partition violence as witness and victim, through personal threats and loss, and the undesired migration completed under duress, seem to have shaped his writing career thereon. Fikr largely gave up poetry as a response, and had said in interviews that poetry could not pay the bills, but also that he wished to connect with people in more accessible language. One can also infer from the preferred mode of his subsequent writing—social satire—that Partition shook him out of Romance. Even if it could not shake his sense of social responsibility and commitment, the subsequent writing is filled with gentle humour which is laughing at the world and the self, prodding for moral improvement but not reliant upon it.

Excerpted with permission from ‘The Sixth River’, by Fikr Taunsvi, published by Speaking Tiger