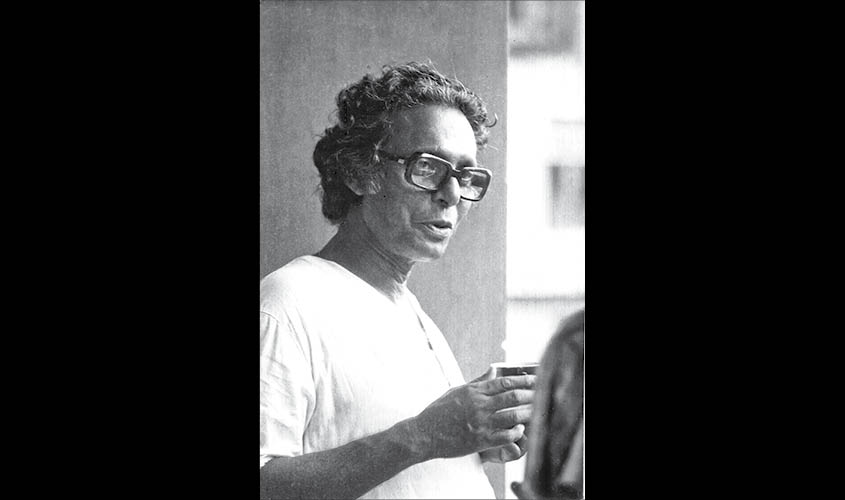

Filmmaker Mrinal Sen, who passed away on 30 December 2018 at age 95, set new benchmarks for Indian cinema with every film of his. Ranked among the great auteurs of all time, he was the master of the cinematic form and an inspiration for young directors around the world, writes Nibedita Saha.

Is there a link between Charlie Chaplin and Mrinal Sen? Most people would be aghast at this seemingly incongruous pairing. After all, Chaplin was a fantasist and comic, whereas Sen remained a level-headed realist throughout his career. But the truth is that Chaplin was the reason Sen decided to become a filmmaker.

“One of the first films I watched when I was eight or nine years old was Chaplin’s The Kid,” Sen said in one of his last interviews, featured in the 2017 Doordarshan documentary, Celebrating Mrinal Sen. “And I loved and loved and loved it…”

In 1972, at the Venice Film Festival, Sen finally got to see Chaplin in person. The latter was being given the Golden Lion Award, and Sen, sitting in the audience, was overcome with emotion. “I wanted to go forward to tell him that I love your work,” Sen recalled in the 2017 interview. “I saw all of your movies and I grow wiser with your films.”

Sen followed Chaplin’s work very closely. He even went on to, late in his life, to write a book on the American filmmaker, entitled My Chaplin, which was published in 2013. But Sen wasn’t interested in mimicking Chaplin’s filmmaking style, as he himself admitted. Originality was what he was after.

Sen’s first feature film, Raat Bhore, was released in 1955, a couple of months after Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali. While Ray’s film became a worldwide success, Raat Bhore generated only a tepid response from the audiences. Sen himself was not satisfied with his debut; later in his career, he evaluated his first film as “pathetic” and “very poorly done”. He even thought of quitting and finding a career other than filmmaking.

It was at this point in his life that he decided to reinvent himself. He set out on a path of self-education, reading books on the history and technique of cinema, and becoming a committed reader of literature in general (many of his films are based on books).

In 1958, his second film, Neel Akasher Neechey, came out, which was more seasoned and impactful than Raat Bhore. But it’s today remembered for all the wrong reasons. The film was banned by the government of India three years after its release, because of its politically-loaded content, and became the first ever film to be banned in independent India.

It was with his third film, Baishey Shravan (1960), that Sen came into his own as a filmmaker. Set in pre-Independence Bengal, the film is unparalleled in its portrayal of human suffering and poverty. It was screened at festivals in London and Venice and earned Sen international renown.

Most of all, Baishey Shravan set a new benchmark for Indian cinema. Students of filmmaking would look back at this masterpiece for lessons on cinematography. And with this landmark, Sen joined the ranks of the greats of Bengali cinema: taking his place next to his contemporaries Ritwik Ghatak and Satyajit Ray.

Sen’s “clash of ideas” with Ray is the stuff of legends. In 1965, after the release of Sen’s Akash Kusum, the two filmmakers exchanged 19 open letters which were published in The Statesman. The correspondence centred on Ray’s critique of Sen’s film, and the latter’s counterarguments. Both had immense respect for each other, but at the same time, they each took a different approach to filmmaking. While Ray remained preoccupied with questions of form, Sen became more and more interested in the “message” that films could convey. “My films,” as Sen wrote in one of his open letters to Ray, “are a kind of thesis.”

Sen was also the more political of the two filmmakers. For subject matter, he delved deep into the social and political crises of his time—from communal riots to the Naxal movement. But his focus remained on human beings, not on political forces. Which is what makes his films so accessible and relatable even today, for audiences and young filmmakers alike.

“Mrinal Da’s integrity, commitment and passion to tell stories have resonated with me in my life and work,” actor and filmmaker Nandita Das told Guardian 20.

She was the main lead in Sen’s 2002 film Aamar Bhuvan. About this experience, Das said, “I had gone to shoot for Aamaar Bhuvan straight after doing Mani Ratnam’s Kannathil Muthamittal. By the time I reached the location, the whole village was somehow involved in the film. Five of us—Mrinal Da, and the main cast and crew—stayed in a small guesthouse. In front of it was the river Ichamati and across, on the other side, was Bangladesh. Mrinal Da used to say the sun rises in Bangladesh and sets in India! This had a special resonance for him as he was born in Faridpur, which is now across the river. On and off the set, we talked as much about the film as we spoke about the fish we were to eat for dinner! He shared many stories from his then 77 years… He asked hard questions that prick our conscience and told stories of ‘ordinary’ people, who are increasingly becoming invisible.”

Shrijit Mukherji, the National Award-winning Bengali director, looks back at Sen’s distinguished career with great fondness and awe. “My favourite movie of Mrinal Sir is Akaler Shondhane. He could bring the nuances of a film within a film structure and break the conventional cinematic devices.”

After Sen’s death on 30 December 2018, at age 95, tributes poured in from all quarters. Political bigwigs as well as Bollywood celebrities posted messages on social media. Sen was celebrated as one of the giants of Indian cinema, loved by all. He received 17 National Awards, as well as Dadasaheb Phalke Award and the Padma Bhushan. But in the wake of his passing, we shouldn’t lose sight of the position he occupied all his life in relation to the mainstream culture.

As filmmaker Gautam Ghosh told us, “Sen was a great Indian filmmaker who never compromised with his art and was never lured by glamour and money. He has inspired a whole generation of filmmakers. He loved experimenting with content and form. And many of his creations were much ahead of their time.”