With epochal credulity, Qafilah said, “For two long years, we kept meeting frequently, we somewhat knew something is going to come out.” In the old city of Srinagar, Junaid Ahmad worked in a local studio as a recording engineer. After recording myriad artists throughout the day, Junaid, in the empty studio, would religiously work on his original music. Arif aka Qafilah, a hip-hop artist, would often visit Junaid and talk about music for hours. Passionate and brimmed with artistic thirst, Junaid and Qafilah would exchange ideas and the ways they could collaborate, and after wearing themselves out from the interminable conversations, every time they would part on the precipice of the same remark, “Let’s create something!”. Never did they create anything, until the day things took a different turn.

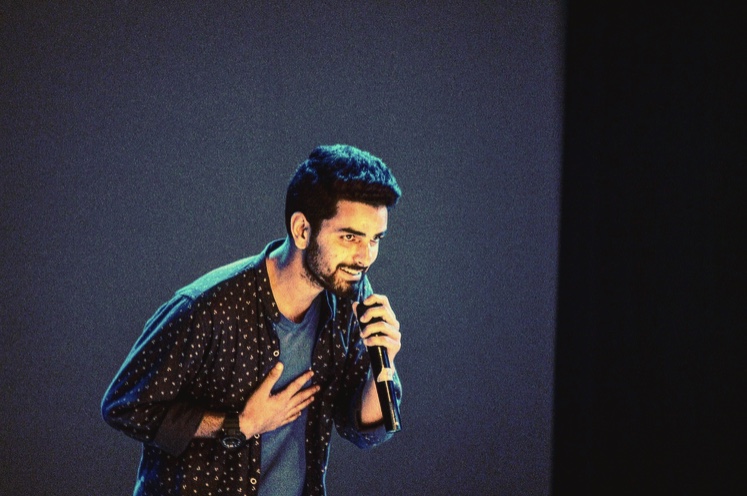

Junaid Ahmed is a music producer and a vocalist specializing in singing Indian classical melodies, and Qafilah sings rap. Both artists, self-taught. And their disciplines poles apart. Thinking about collaboration would not be anything new, but it would be certainly a dauntless decision. Nevertheless, one fine day, they did not leave the studio early. The major part of the song was done in that sitting.

“I picked up the guitar and plucked a few chords, and Qafilah writes an intro, which I sang. He wrote a verse too, on which he would rap,” said Junaid. It did not end there, they recorded the vocal tracks there too, and never took a new take. Although a major chunk of work was done there, the song, yet to be titled, would go through a rigorous re-drafting process.

“I can show you my phone, there are at least 200 versions/drafts of The Lost Shikara. It was not difficult, but excruciating, at one point in time I’d doubt whether the song will come out at all,” says Qafilah.

The Lost Shikara has an uncanny structure— there’s a melodic chorus which is sung by Junaid, and there are verses that Qafilah delivers through his unparalleled rap. The lyrics of the song depict the river Jhelum as a personified object—witness to a collective memory.

“Jhelum is the lifeline, a river which flows right through the heart of the capital city Srinagar. Banks of the river have been like stages of a theatre, where things happened. Good days and the bad days, misery and harmony, Jhelum has been a witness to all of it,” says Junaid.

However, Qafilah adds more to the interpretations of the song: “The song is about the internal and the external conflicts. The conflicts within the human heart and the peripheral tumult all of us live in every day.”

“I wrote the song when I was at the lowest of my life, probably everything had fallen apart, and surprisingly music was probably not a beloved anymore,” Qafilah added.

Although the song was a cathartic vent for the rapper, for Junaid, the essence of the song pertains to liberation from worldly burdens. It is a meditation, or you could say an introspective meditation. A thread via which one connects to the creator.

The intro, which is the chorus too, has been sung beautifully by Junaid in Kashmiri. The lines translate to:

“Are you searching through words?

Or are you waiting on the banks of Jhelum?

Shrines call for prayers nevermore,

Are you a weary bird, fallen from the sky?

What are you confiding in the mountains afar?

Are you killing the desire within you?

‘All that glitters is not gold’

Don’t you remember?”

Moreover, the noteworthy experiment in the song is a very intricate Rabab solo, which is played by the renowned Rababist from the valley, Adnan Manzoor. The solo is groovy and also retains the tinge of Kashmiri folk music, and this in unison compliments the whole arrangement.

The song was received amid