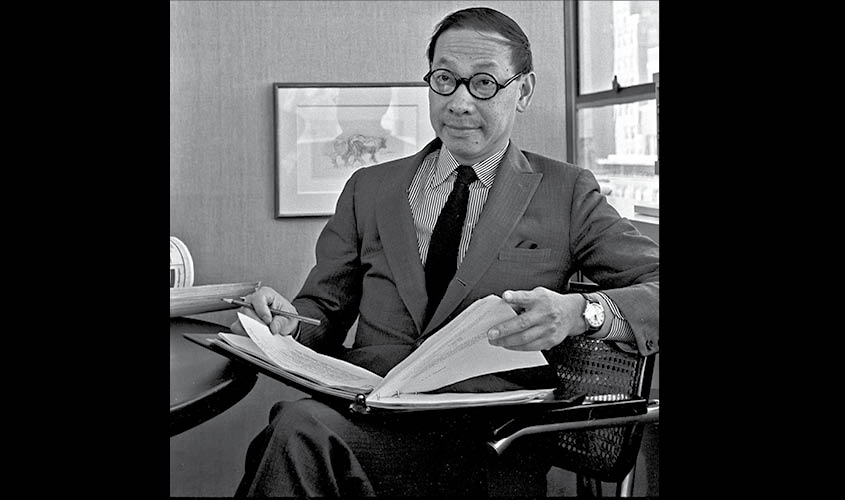

I.M. Pei, who began his long career designing buildings for a New York real estate developer and ended it as one of the most revered architects in the world, died early Thursday at his home in Manhattan. He was 102.

His death was confirmed by his son Li Chung Pei, who is also an architect and known as Sandi. He said his father had recently celebrated his birthday with a family dinner.

Best known for designing the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the glass pyramid at the entrance to the Louvre in Paris, Pei was one of the few architects who were equally attractive to real estate developers, corporate chieftains and art museum boards (the third group, of course, often made up of members of the first two). And all his work—from his commercial skyscrapers to his art museums—represented a careful balance of the cutting edge and the conservative.

Pei remained a committed modernist, and while none of his buildings could ever be called old-fashioned or traditional, his particular brand of modernism—clean, reserved, sharp-edged and unapologetic in its use of simple geometries and its aspirations to monumentality—sometimes seemed to be a throwback, at least when compared with the latest architectural trends.

This hardly bothered him. What he valued most in architecture, he said, was that it “stand the test of time.”

Pei, who was born in China and moved to the United States in the 1930s, was hired by William Zeckendorf in 1948, shortly after he received his graduate degree in architecture from Harvard, to oversee the design of buildings produced by Zeckendorf’s firm, Webb & Knapp.

Pei quickly found himself engaged in the design of high-rise buildings, and he used that experience as a springboard to establish his own firm, I.M. Pei & Associates, which he set up in 1955 with Henry Cobb and Eason Leonard, the team he had assembled at Webb & Knapp.

In its early years, I.M. Pei & Associates mainly executed projects for Zeckendorf, including Kips Bay Plaza in New York, finished in 1963; Society Hill Towers in Philadelphia (1964); and Silver Towers in New York (1967). All were notable for their gridded concrete facades.

The firm became fully independent from Webb & Knapp in 1960, by which time Pei was winning commissions for major projects that had nothing to do with Zeckendorf. Among these were the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, completed in 1967, and the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York, and the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa, both finished in 1968.

They were the first in a series of museums he designed that would come to include the East Building in Washington (1978) and the Louvre pyramid (1989) as well as the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland.

The Cleveland project would not be Pei’s last unlikely museum commission: His museum oeuvre would culminate in the call to design the Museum of Islamic Art, in Doha, Qatar, in 2008, a challenge Pei accepted with relish. A longtime collector of Western abstract expressionist art, he admitted to knowing little about Islamic art.

As with the rock museum, Pei saw the Qatar commission as an opportunity to learn about a culture he did not claim to understand. He began his research by reading a biography of the Prophet Muhammad, and then commenced a tour of great Islamic architecture around the world.

Besides his many art museums, he designed concert halls, academic structures, hospitals, office towers and civic buildings like the Dallas City Hall, completed in 1977; the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, finished in 1979; and the Guggenheim Pavilion of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, finished in 1992.

(I.M. Pei & Associates eventually became I.M. Pei & Partners and later named Pei Cobb and Freed.)

In 1979, the year after the National Gallery was completed, Pei received the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects, its highest honor.

At the same time that he was receiving plaudits in Washington, however, Pei was recovering from one of the most devastating setbacks any architect of his generation had faced anywhere: the nearly total failure of one of his most conspicuous projects, the 700-foot-tall John Hancock Tower at Copley Square in Boston.

A thin, elegant slab of bluish glass designed by his partner Henry Cobb, it was nearing completion in 1973 when sheets of glass began popping out of its facade. They were quickly replaced with plywood, but before the source of the problem could be detected, nearly a third of the glass had fallen out, creating both a professional embarrassment and an enormous legal liability for Pei and his firm.

The fault, experts believed, was not in the Pei design but in the glass itself: The Hancock Tower was one of the first high-rise buildings to use a new type of reflective, double-paned glass.

The building ultimately won numerous awards, including the American Institute of Architects’ 25-Year Award.

Ieoh Ming Pei was born in Canton (now Guangzhou) on 26 April 1917, the son of Tsuyee Pei, one of China’s leading bankers.

He was brought up in a well-to-do household that was steeped in both Chinese tradition—he spent summers in a country village, where his father’s family had lived for more than 500 years, learning the rites of ancestor worship—and Western sophistication.

He decided to attend college in the United States. He received a bachelor of architecture degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1940.

While he was at MIT, Pei met another Chinese national, Eileen Loo, who had come to the United States in 1938 to study art at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. The two married as soon as she graduated, in 1942. Eileen Pei began graduate work in landscape architecture at Harvard while her husband worked toward his advanced architecture degree, which he received in 1946.

Pei never played down his connections to China. His children were all given Chinese names, and when he won the Pritzker Prize in 1983, widely viewed as the highest honor a living architect can receive, he used the $100,000 award to establish a scholarship fund for Chinese architecture students.

His eldest son, T’ing Chung, an urban planner, died in 2003. His wife of 72 years, Eileen, died in 2014. In addition to his son Li Chung, who is known as Sandi, he is survived by another son, Chien Chung, also an architect, who is known as Didi; his daughter, Liane; and grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

© 2019 The New York Times