Just a year over a decade after the gruesome events of Jallianwala Bagh, and a month after the triumphant Dandi March, another Black Day descended on British India, on the history of India’s freedom struggle. A day that seems to have been erased from historical memory. Partly because the tragedy occurred in Peshawar which falls in present day Pakistan. What sparked if off though, was basically the underlying demand of Independence for an undivided India. Events that unfolded on that fateful day, 23rd April 30, I930, draw a striking parallel to the massacre of Jallianwala Bagh in I9I9. The British troops, obviously with the support of the civilian administration, were at it again, firing upon and killing innocent unarmed civilians gathered for a peaceful protest. Hundreds of protestors were martyred at Qissa Khwani Bazaar in Peshawar the headquarters of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP). Whereas the official death toll placed the fatal casualties at a mere 30, unofficial sources revealed that the death toll was around 400.

The root cause of the tragedy was the imposition, by the Colonial Government of the Frontier Crimes Regulation. The Regulation, comprising a stringent set of rules, denied the people, a majority of whom belonged to the Pashtun Tribe, the basic rights of appeal, namely the right to challenge a conviction in a court of appeal, the right to legal representation and the right to present reasoned evidence. The immediate provocation for the peaceful protests was the denial of permission to a team of leaders of the Indian National Congress, to enter the NWFP. The team whose purpose was to investigate the Regulation and its impact, was detained in the Punjab.

The protest was organised Khudai Khidmatgar (‘Servants of God’), an organisation committed to nonviolence, set up in 1929 by Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, popularly known as the Frontier Gandhi. His commitment to non-violence was internationally acknowledged and the organisation emerged as the first non-violent army in the world. Its primary objective was ousting the British Rule by peaceful means as also to strengthen the ties among Pashtuns, plagued by centuries of fratricidal warfare.

Hundreds of Khudai Khidmatgars, assembled at the Peshawar railway station to receive the Congress leaders, resorted to a massive non- violent demonstration. Around the same time Ghaffar Khan was arrested after his a speech in Utmanzai urging resistance to British colonial rule. Several prominent leaders like Ghulam Rabani and Abdur Rehman Atish were also arrested while addressing a public gathering. In strong protest peaceful demonstrations were organised in the Qissa Khwani Bazaar in Peshawar.

Qissa Khwani or Story Tellers’ Bazaar, in the heart of Peshawar, is famous for Chai and Qehwa houses. Besides, the city was home to Indian film celebrities like Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor prior to partition. The Bazaar›s name originates from a historic tradition. Traders from Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent mingled in the market›s crowded tea houses to exchange stories. The Indo-Islamic style of architecture is still visible in the dilapidated facades of the Bazaar’s buildings, known apart from their tea shops, for their book shops, publishers and mithai (sweets) shops.

The Deputy Commissioner of Peshawar, Metcalfe, is said to have over reacted and ordered armoured cars to enter the area and assess the situation. The cars reportedly drove over at least six men two of whom were crushed to death. Slogans like “Inquilab Zindabad” and “Allah o Akbar” rent the air, together with calls for the destruction of the British Empire. Incidentally the sloganeering was led by a Sikh youth.

A British Officer probably seized by panic, opened fire on the crowd. This was followed immediately by machine gun fire from the armoured vehicles. According to the then District Judge Saadullah Khan, the first round of shooting lasted for about ten to fifteen minutes.

The demonstrators however continued their commitment to non-violence, offering to disperse on two conditions. One that they be permitted gather their dead and injured, and the second that the British Indian Army (BIA) should leave the square. The BIA refused. Half an hour later, a second round of shooting commenced. The crowd retaliated by hurling bricks. One car was set ablaze. A BIA despatch rider was killed and his body burnt

Troops of the 18th Royal Garwhal Rifles, who were ordered to open fire refused to shoot at their fellow countrymen. Instead they retreated in the face of the crowd which was advancing with wooden sticks. Finally it was the men of the King’s own Yorkshire Light Infantry who opened fire. As the crowd scattered, the Yorkshire troops advanced into the Bazaar gunning down people mercilessly. The shooting was so indiscriminate that even a police constable’s horse was killed.

The violence continued for six hours. According to Abdul Hamid an eyewitness, a young man probably wounded and wanting to run away after picking up his turban was again fired at and killed. Another man carrying a baby in his arms was shot. He fell down and a British soldier took the child and threw it aside.

Gene Sharp, in a study of nonviolent resistance, describes the scene on that day: “When those in front fell down wounded by the shots, those behind came forward with their chests bared and exposed themselves to the fire, so much so that some people got as many as twenty-one bullet wounds in their bodies, and all the people stood their ground without getting into a panic. . . . This state of things continued from 11 in the morning till 5 o›clock in the evening.”

The next day, on April 24, the Royal Garhwal Rifles refused to patrol Peshawar city. When ordered to return their rifles they refused to comply. A non-commissioned officer is reported to have replied that the Indian Army was meant to protect India from external invasions and not to function within the country.

As many as 17 men of the Royal Garhwal rifles were imprisoned for disobeying orders to shoot the protesters. Havildar/Sergeant, Chander Singh who led one of the platoons was sentenced to life in exile. The rest were sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour ranging from three to ten years. Very few could afford legal representation.

Records revealed that no other regiment of the Indian Army had won greater glory in the World War I than the Garhwal Rifles. Their defiance at this juncture sent shock waves throughout Government circles in India and Britain. Many members of the establishment viewed this as an omen of graver things to come in the future.

Post the Kissa Khwani Bazar massacre, the Colonial Government unleased a brutal crackdown on the Khudai Khidmatgar. Members were subjected to all kinds of harassment which included physical violence and religious persecution. In defiance the movement began involving young women volunteers. The machinery of state then retaliated with physical violence and abuse of the women.

As though the events of April 23, 1930 were not horrendous enough, again on May 31, 1930 at least six people were killed and eight wounded when soldiers from the Essex Regiment fired on a funeral procession near the entrance of Gorkhatri, a public park in Peshawar. The funeral was of several Sikh children who had been murdered that very day by British troops.

The occurrences in Peshawar created numerous instances of unrest throughout British India. Succumbing to public pressure, King George VI (Emperor of India) ordered a judicial enquiry. The Commission put up its case before Chief Justice Naimatullah Chaudhary, a distinguished Judge, who personally surveyed the area of the massacre and published a 200-page report indicting the BIA. Justice Chaudhary was subsequently knighted by the Imperial Government. However there are no records of any stringent action taken against the troops.

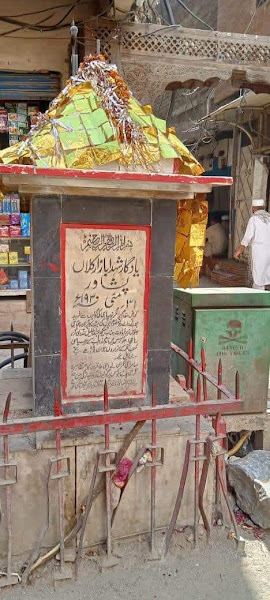

In 1932, in a move that took the colonial government completely by surprise the Khudai Khidmatgar aligned themselves with the Congress. The organisation strongly opposed Partition, a stance that was interpreted by the future powers that be, as the movement not being in favour of the creation of the independent nation of Pakistan. Post 1947, the political influence of the Khudai Khidmatgar deceased rapidly and it was gradually relegated into oblivion. Ironically the colonial Government did not permit the construction of a memorial at the site. A memorial put up by local residents was immediately raised to the ground. Post independence of course memorials have been constructed at different spots where the shooting took place.

In the immediate aftermath, the sacrifice of the martyrs did not go in vain. Gradually colonial control over Peshawar loosened as protests swept across different areas in the subcontinent. Referring to the Khudai Khidmatgar, Ghaffar Khan wrote in his autobiography My Life and Struggle that for the British, a nonviolent Pathan was more dangerous than a violent one and hence, they tried everything to provoke them into violence but failed. Sadly, succeeding generations seem to have completely obliterated this from the records of history.