For years, scientists have been refining techniques to determine the age of a painting using radiocarbon dating and the lingering effects of mid-20th-century nuclear tests. Now researchers are using the same methods to identify cases of art forgery, writes Niraj Chokshi.

How can you tell if a painting is a modern forgery? Mid-20th-century nuclear bomb tests may hold a clue.

For years, scientists have been refining techniques to determine the age of a painting using radiocarbon dating and the lingering effects of the tests. Now, a team of researchers has dated one such artwork using a paint chip the size of a poppy seed, according to a study published Monday in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It’s an amazing technical achievement,” said Greg Hodgins, a professor at the University of Arizona who oversees a lab dedicated to radiocarbon dating and was not involved in the study.

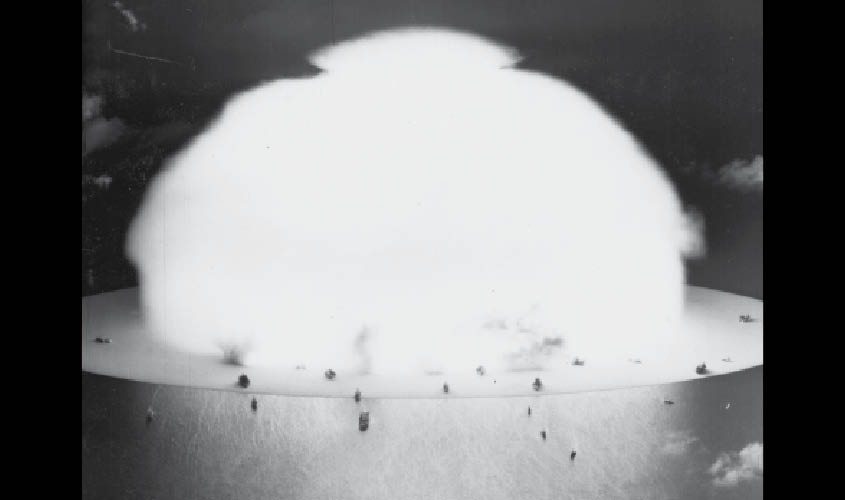

The “bomb peak”

Developed in the 1940s, radiocarbon dating allows scientists to determine the age of a wide range of materials—including fossils, cave paintings, parchment and even human remains—by examining the types of carbon atoms they contain.

Atoms of a single element but of different masses are known as isotopes. The carbon 12 and carbon 13 isotopes are stable, while carbon 14 is unstable. The mix of those isotopes is consistent among living things, but once organic matter dies its carbon 14 atoms decay. As a result, scientists can determine the age of dead organic matter up to tens of thousands of years old by calculating the ratio of those carbon isotopes.

But that formula was drastically disrupted a little over half a century ago, with the advent of nuclear testing.

Carbon 14 is naturally created when high-energy cosmic rays collide with nitrogen atoms in the atmosphere. But the powerful aboveground nuclear bomb tests of the mid-1900s created even more carbon 14 isotopes out of that atmospheric nitrogen. In fact, so much carbon 14 had been created in the decade or so leading up to the signing of the partial nuclear test ban treaty of 1963 that levels in the atmosphere virtually doubled.

“This bomb peak is really a unique signature,” said Laura Hendriks, a doctoral candidate at E.T.H. Zurich in Switzerland and the lead author of the study, referring to the spike in atmospheric carbon 14. “It can be used in so many different fields, it’s just unbelievable, although it’s not a good thing.”

The effect of the bomb tests was akin to advancing a clock, according to Hodgins. “In cosmic carbon dating terms, it’s kind of like moving 5,000 years into the future,” he said.

That increase in carbon 14 was reflected in anything that lived or died after 1963, including wood and fibres that might make up the support or canvas of a modern work of art or the organic matter used to bind pigments in modern paint.

Putting it to the test

The idea of identifying forgeries by dating the binder used in paint, as Hendriks and her colleagues did in their study, was proposed at least as far back as 1972. And in 2015, experts in Italy used canvas fibres to determine that a painting purportedly by French artist Fernand Léger and owned by the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation was actually a fake.

But there have always been ways to circumvent that technique. Forgers have reused old to create forgeries, neutralising the effectiveness of testing canvas fibres. And historically, large samples were needed to conduct the analyses. (When scientists in the late 1980s determined that the Shroud of Turin, Jesus’ reputed burial cloth, was a forgery, they used samples the size of postage stamps for their radiocarbon tests.)

In the study published Monday, the samples the team used were vanishingly tiny. Recent technological advances enabled the researchers to analyse hairlike strands of canvas fibre a few millimetres long and a paint sample that measured about half a square millimetre in area.

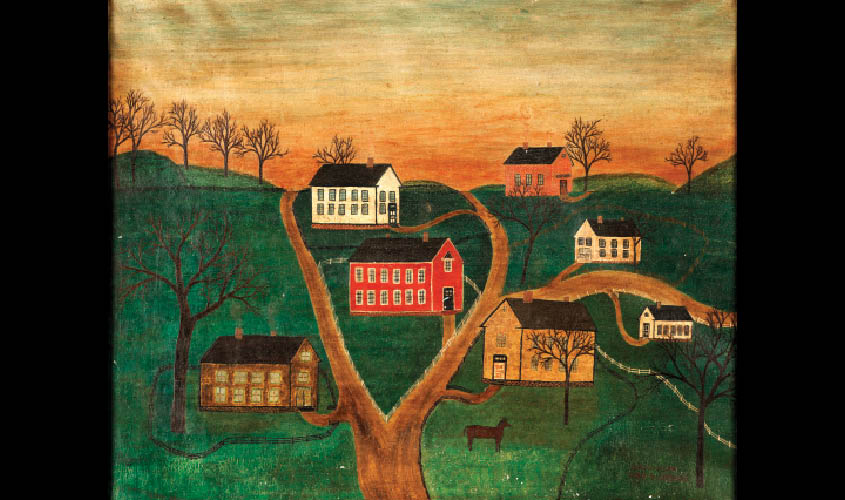

The samples were taken from a known forgery, a painting of a 19th-century village scene that was claimed to have been created in 1866. In reality, the work had been painted in the 1980s by Robert Trotter, an artist who was later jailed and fined for selling dozens of such fakes. A judge ordered some of those paintings to be handed over to experts for the purpose of studying forgers’ methods.

To prepare the samples, the team first cleaned them in solvent and acid washes to remove contaminants and varnishes. Then, it heated the samples to about 1,750 degrees Fahrenheit to release carbon dioxide, Hendriks said. That gas was captured and placed in a particle accelerator, where the carbon atoms from the sample were sorted and compared.

The results for the canvas fibres were inconclusive. Trotter recycled old canvases for his forgeries, he said, and the fibres could be dated to anytime from the end of the 1600s to the mid-1900s, Hendriks and her colleagues found.

The binder in the paint told a different story. It was fresh when the work was created, Hendriks said. According to her team’s analysis, the oil used as the binder for Trotter’s painting contained an excess of carbon 14 and came from seeds harvested either from 1958 to 1961 or from 1983 to 1989 — long after the fake date of creation initially provided by Trotter.

“Not a silver bullet”

As useful as the method outlined in the study may be for identifying forgeries, it is not without limitations.

“It’s an important advance, but it’s not a silver bullet,” Hodgins said.

Radiocarbon dating is, by definition, destructive. While the team behind the study showed that it was possible to conduct the analysis using tiny samples, they still needed to remove material from the actual painting. In addition, clearing the sample of potential contaminants can prove difficult.

And the usefulness of the bomb peak appears to be expiring, too. Levels of carbon 14 in the atmosphere are on course to return to prebomb levels after being absorbed by the ocean and are expected to fall further as they continue to be diluted by fossil fuel emissions. As a result, radiocarbon dating in the future will likely yield multiple results from before and after the bombing period.

The technique will most likely retain some value, but it will increasingly need to be used in conjunction with other methods of ascertaining a material’s age, experts say.

“It can still be useful, but it’s going to be more and more difficult,” Hendriks said. “It’s kind of like a puzzle coming together.”

2019 ©THE NEW YORK TIMES