Perumal Murugan, after having famously committed ‘literary suicide’ in 2015, has returned with a parable about village life, written with breathtaking and deceptive simplicity, writes Parul Sehgal.

In her Nobel lecture, delivered in Stockholm earlier this month, Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk surveyed the world of letters with dismay. What happened to its power and promise? she asked. What happened to its mandate to yank us out of our lives and into confrontation with the universal, to bind us to history and one another? Instead, we are deafened by a cacophony of memoirs and first-person narratives—“a choir made up of soloists.” Tokarczuk lamented the decline of the fable as a form, and the loss of literature as a site for radical tenderness that might militate against self-obsession and refresh our sensitivity to the world.

I confess I had no idea things were quite so bad. But don’t despair, Olga Tokarczuk. I have an antidote at hand.

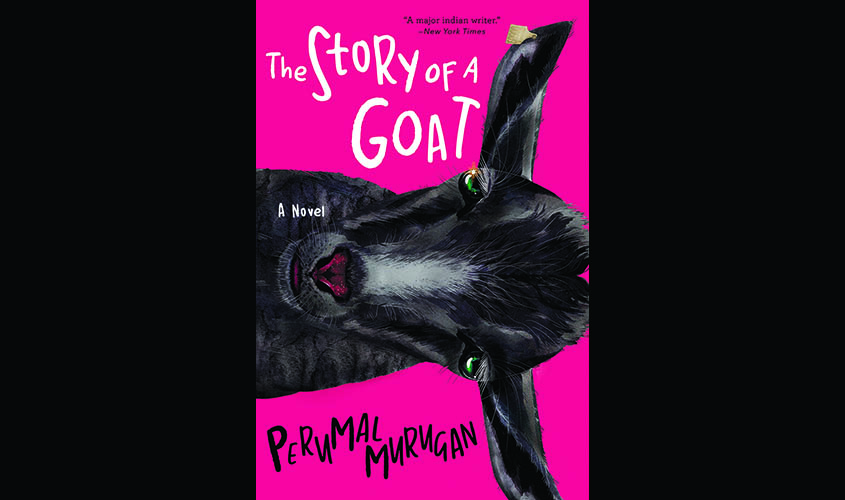

The Story of a Goat is the newly translated novel by Perumal Murugan, his first work since he famously committed literary suicide in 2015. Right-wing Hindu groups had attacked him for his book One Part Woman, which depicted an ancient temple ritual that permitted childless women to sleep with strangers in the hope of getting pregnant. Murugan was driven from his village and coerced into an apology. He renounced writing. “Perumal Murugan the writer is dead,” he posted on Facebook. “Leave him alone.”

A court ruling defended his right to free expression, and Murugan returned to work, albeit badly shaken. He was reluctant to write about humans, he said (“a censor is seated inside me now”), never mind his favourite incendiary themes: caste politics and the blunt, brutal power of the mob.

Thank God for goats.

Perumal Murugan the writer lives, fearless as ever. He has returned with another parable about village life, written with breathtaking and deceptive simplicity, translated from the Tamil by N. Kalyan Raman. The novel examines the oppressions of caste and colourism, government surveillance, the abuse of women—all cunningly folded into the biography of an unhappy little goat.

There might be no more benighted animal in all of literature than Poonachi, the seventh and smallest of her litter. She slides out of her mother’s body, soot-black and frail as a flower.

An old farmer and his wife assume her care. To their surprise, their quiet home is filled with new warmth and purpose. “It had been a long time since there was such pleasant chitchat between the couple. Because of the kid’s sudden entry into their lives, they ended up talking about the old days.” They fatten her up and introduce her to their herd. She grows into an observant creature, slow to anger and bashful about her belly, still bloated from early hunger, and her matted hair. She clings to the old couple like a child.

However venerable, the tradition of encoding critiques of power in animal stories has always left me feeling leery. The very words “baby goat” act on my brain in ways I intensely resent. But Murugan, who tended his family’s goats until he was in his 20s, writes about animal life (and death, lust, resentment) without a whiff of sentimentality. He grew up with these animals. He knows that the jaws of baby goats ache the first time they nurse. He knows the smell of a cobra in the dark.

There’s a certain kind

And how the little goat suffers. She watches her playmates get castrated when they reach sexual maturity. She falls in love. (Murugan writes a disconcertingly effective goat sex scene.) The old woman refuses to be parted from her little pet, however, and Poonachi is separated from her beloved. She burns with rage at her human mother. She is bred, violently. Famine stalks the land.

The peculiarities of this society creep into the story. Each new baby—human or animal—must be tallied, and their ears pierced. Farmers and herders face a harsh interrogation about the parentage of their creatures—particularly those in possession of black goats, which are regarded with hostility. Originally published in 2016, the novel feels prophetic, anticipating the new law in India that grants citizenship to migrants on the basis of religion, transforming it, in effect, into a Hindu nationalist state.

Murugan traces the entire life of his little goat—her despair, her small acts of heroism, her longing—with Chekhovian clarity. Each sentence in Raman’s supple translation is modest, sculpted and clean, but behind each you sense a fund of deep wisdom about the vagaries of the rains, politics, behavior—human and animal. It was Chekhov who once said that anyone could write a biography of Socrates, but it takes skill to tell the stories of all the smaller, anonymous lives.

“Once, in a village, there was a goat,” the book begins. “The birth of an ordinary creature never leaves a trace, does it?” We are all such ordinary creatures, Murugan reveals; if any of our fugitive traces remain, we leave them in one another’s hands.

© 2019 THE NEW YORK TIMES