After four months of lockdown and restrictions, the online theatre scene has only strengthened its presence in India. But do the pros outweigh the cons? People from the community share their experiences with how the form has pushed the boundaries of their practice so far.

Kaivalya Plays, an independent theatre collective in Delhi, was scheduled to stage Álvaro Menéndez Leal’s Luz Negra in April, when the world went into lockdown. Instead of abandoning the production, the director, Gaurav Singh, took along his actors to Skype and streamed the play live using Open Broadcaster Software. The performance recorded 700 unique visitors—considerably more than what the Spanish-language play would have invited at a standard Delhi auditorium.

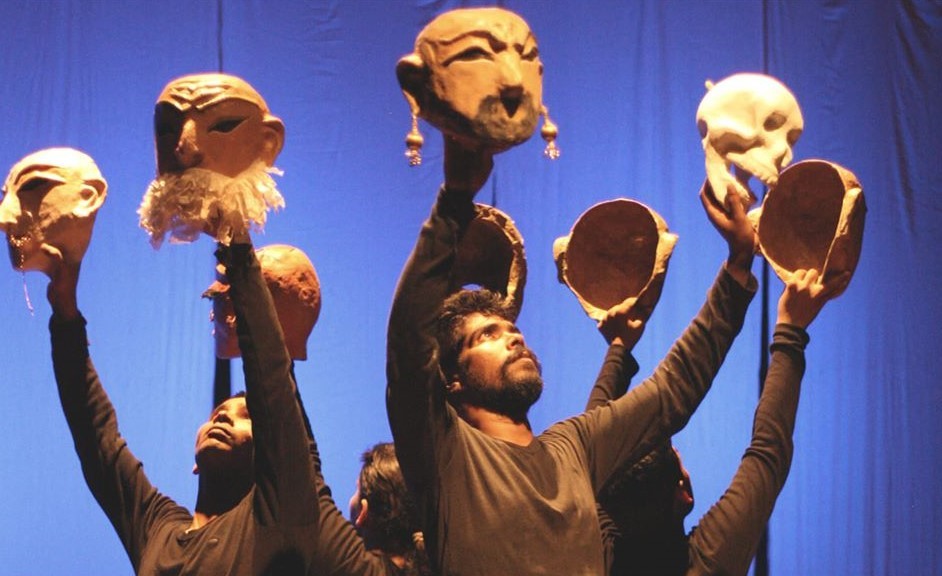

Like most of the arts, theatre in India too has had to migrate online in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. From airing pre-recorded plays to presenting “live” performances on platforms like Zoom and Instagram, the theatre community has had to embrace the digital space faster than before. The questions which arise now pertain to how sustainable, accessible and accepted the form becomes in the long run. “Artists cannot afford to be stuck,” says Anurupa Roy, founder of The Katkatha Puppet Arts Trust, adding, “We have to adapt our art to the world, instead of waiting for the world to change.” Katkatha is one of the groups which have moved completely online over the last four months, with shows, workshops and even a fundraising festival being conducted online successfully. “We might not be touring, but our work is still travelling.”

The dissolution of geographical boundaries has been one of the most exciting aspects of online theatre for a lot of groups. Besides being able to team up with actors and technicians from all over the world, the reach of these performances has also seen a massive jump. After screening one of their shows, Roy found that it had been seen simultaneously in 25 countries. “The demographic ramifications of this are huge,” says Sanjay Kumar, who founded and directs for Pandies’ Theatre. The group recently performed Clifford Odets’ Till The Day I Die live on Zoom, and despite being subjected to a new form of theatre and the technical glitches which came with it, “about 85 people sat till the end”, reports Kumar. But have audiences warmed up to the idea of watching theatre on their laptops and smartphones already? “The audience for this definitely exists,” says Amitesh Grover, interdisciplinary artist and assistant professor at the National School of Drama. “Just look at the hits for comedians and musicians online,” he points out.

The onus of tapping into that potential audience now rests with theatre companies. But to put up spectacular online performances one needs to adapt to acting and producing at home on a computer. This has raised questions on the quality and experience of such productions too. Eminent theatre personality associated with the legendary Yatrik Theatre, Sunit Tandon, says, “It is different when a play performed on stage with a live audience is recorded professionally and screened, but on a livestream, audio and video quality has to be compromised with. It cannot make for a good experience, especially for audiences.”

So how are theatre companies handling technicalities? Sanjay Kumar collaborated with a skilled tech team in Mumbai for his play, while Anurupa Roy taught herself the basics of streaming software. Gaurav Singh walked a mile further for his audience and arranged English subtitles for Luz Negra, which were put on 600 Google Slides and synced with the dialogues in real time. Lights, sound, set design and action are all being adapted to fit a videoconferencing platform too. “The fade-in and fade-out for character transitions (for Luz Negra) could be controlled using the brightness of our monitors, and being able to switch our video background to place performers in a dilapidated 19th century town plaza made the performance more compelling to watch, even if it was online,” said Singh. “The limitations of online platforms can also be used as advantages,” says Kumar. “For instance, if we have 15 actors on camera, it also brings 15 different spaces to the play at once, each meaning something. The potential for interpretation is thrown wide open,” he adds.

But with this entire exercise being so dependent on technology and the required know-how, who can afford to put up online plays as well as watch them? Sudhanva Deshpande of Jana Natya Manch, a leftist street-theatre group, admits that the form exists in a zone of relative privilege at the moment. “Even the huge problem with online teaching right now points to the fact that there isn’t some utopian level playing field out there.” Others argue that the infrastructure exists, especially with the ubiquity of smartphones and internet packs. However, possessing the tools does not equal to knowing how to use them. Besides educating oneself in the tricks of online theatre, active workshops organised by the community can help learners, says Anurupa Roy. Kaivalya Plays has also started a virtual Theatre Management Fellowship which aims to fill this gap with practical workshops on tools and technologies for performing arts professionals. The programme has received over 90+ applications for its first edition. However, online theatre will have to gain more ground before it receives such encouragement from larger institutions like a National School of Drama. “Pedagogical support will only follow practice and not the other way around,” says Amitesh Grover.

There is also dispute over whether the form can even be counted as theatre. “To me, the most basic idea of theatre involves the performer and the audience sharing the same physical space—not virtual,” says Deshpande. “This is why I hesitate to call these online “plays”, but “performances”,” he says. Tandon also agrees that the form cannot be called theatre, but is a good exercise at the moment for artists to stay engaged with their craft and their audiences. Grover contends that there is too much resistance towards change, especially regarding performance and visual culture in the country. “Why can’t digitality be a part of them?” he questions. Sanjay Kumar states that the community is constantly defining theatre for itself, while Anurupa Roy says that theoretical concerns can be dealt with later. “Ask these questions when this is over. Right now, it is crucial to keep human-to-human contact alive, stories alive,” she says.

But with the end of the pandemic nowhere in sight, will online theatre become the norm? Gaurav Singh is enthusiastic about it being the next big thing waiting just around the corner. Grover disagrees: “It will not become mainstream, not until we have years of dedicated online theatre.” Sunit Tandon, Anurupa Roy and Sanjay Kumar echo this sentiment. “Only time will tell how worthwhile this ends up being—but it will never be a substitute for the real thing,” says Tandon. Roy also thinks that the digital form can exist as a parallel to the physical form, but never as a replacement. Meanwhile, Kumar says, “It can be built as an alternative but powerful sub-genre, especially since some plays can work very well on a screen.” However, the one thing that everyone agrees with is how they can experiment like never before. Perhaps it is heartening for enthusiasts of the form to note that most groups have online performances lined up until the end of the year.

Going forward, some concerns still remain. Gaurav Singh points to a possible debate arising in the future about privacy issues regarding acting in or attending a performance on the internet. Moreover, while a platform like Zoom makes it possible to fiddle with audio and video controls and engage audiences in more innovative ways, it can also dilute the experience if it resorts to too much gimmickry. More questions still hang in the air, especially the entire economic model of this sort of theatre, thinks Deshpande. While Singh and Kumar laud the relatively lower costs of putting up online performances right now, Singh also says that the community needs more clarity on “what, how, why and why not to charge” for watching an online performance. Roy says that independent and traditional theatre groups struggling to keep up with the digital transition right now also hints at policy failures which have left them utterly uninsured.

Challenges apart, Roy also feels that the digital space is a more democratic space, which eliminates the middleman of the producer or agent, and exposes theatre, especially traditional forms, to newer audiences. As for the concern about making online performances reach every corner of the country, Roy says that if an artist wants their work to get out, they will always find a way. “Solutions can always be found—maybe not today, but next month,” she says, adding, “Besides, when did theatre ever exist without a crisis?”