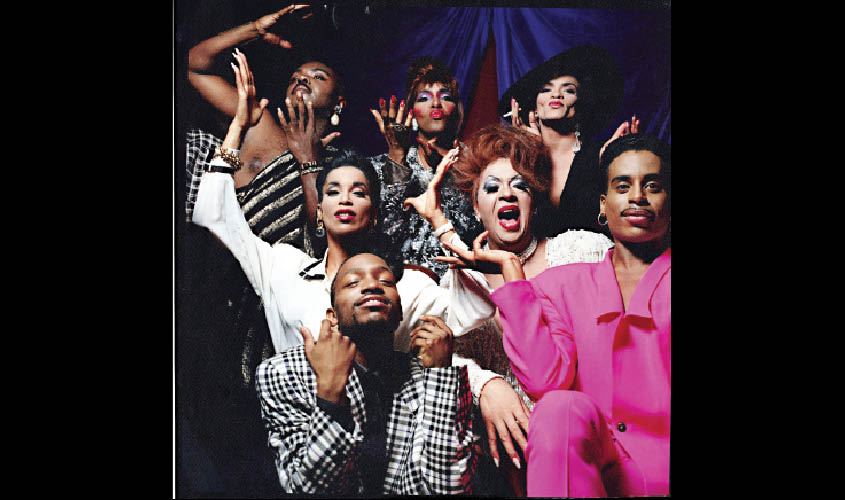

For many LGBTQ people, June signals rainbows and glitter, but also reflection. With the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising and the WorldPride festival colliding in New York this Pride Month, it’s an especially momentous time to look to the past to consider what Pride means today, and cinema—long an integral part of queer artistic expression—can be an important tool. Many of the city’s repertory movie theaters have assembled special programs for the occasion, from revivals of Paris Is Burning (Film Forum) and The Queen (IFC Center) to a series looking at queer cinema before and after Stonewall (Museum of the Moving Image).

As ideas about queerness have expanded, so has our engagement with media that reflect those experiences. Nick McCarthy, director of programming and operations at NewFest, stressed the value of regular programming and its potential to create community. “It’s equally important that the contemporary stories told through queer cinema continue to mirror not just the progress but the evolution of our community,” he said. While NewFest is best known for its annual film festival, it produces year-round programming, which McCarthy said is “essential to serving the community in order to see themselves reflected on screen.”

One such programme is OutCinema, a three-day event presented in part with NYC Pride. McCarthy also hosts a monthly screening and talkback series at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center, as well as a monthly retrospective series at the Quad called Coming Out Again (which will be screening Gay USA on June 26).

One of the challenges in creating this programming is the looming threat of streaming services, where a seemingly endless amount of content is always available. The Metrograph is countering that with Films of Pride and Protest, a program of shorts not easily found on digital services. And Adam Baran, who programs the Queer/Art/Film series with movie director Ira Sachs, said that he suggests alternative titles if a proposed selection is either too present on streaming, or screens in New York too often.

Niche streaming services like Dekkoo offer a home for gay movies, but, as Michael Koresky, editorial director at Film at Lincoln Center, noted, the quality of their output is inconsistent. “There’s a lot of product out there, made cheaply, and, not unlike porn, it’s churned out to appeal to a hungry demographic,” he said.

The major streaming services create an illusion of access and community sans shared physical space; the LGBT movie sections on Netflix and Hulu might have a handful of gems, but their selection is limited, even as they debut original programming. The alternative streaming platforms for gay cinema have yet to break out, and Baran remarked in a phone interview on the challenges of the market. “It’s very hard to know what a gay audience wants, especially a gay audience willing to spend money,” he said.

So how important is it for gay audiences to be able to gather together—in person—to view these films? Will gay audiences spend money on these specialty repertory programs, like the German-focused Queer Kino at the Quad or the tongue-in-cheek presentation of “The Babadook,” whose horror villain was memed into a gay icon across social media in 2017, at IFC Center? Will they be drawn to Koresky’s salon-like panel “Queer & Now & Then” to catalyse them to consider past, present and futures of queerness and cinema?

“It needs to be encouraged in our community to actively have these dialogues in person to strengthen the fabric, identity, and impact of our community’s ethos,” McCarthy noted.

In addition to providing tangible community, programmers—with goals both political and artistic—hope to give audiences new ways to look at queer subjects.

“The programming doesn’t only show films by trans filmmakers, or only films about trans subjects or the experiences of trans characters, but tries to imagine what a trans lens can bring to films that more loosely explore trans-adjacent themes,” said D’Angelo Madsen Minax, who works with Joey Carducci on a series at Anthology Film Archives called The Cinema of Gender Transgression: Trans Film, of their mission.

Carducci added, “I think it’s crucially important to make space for this kind of work, now and always.”

Stonewall 50 and WorldPride provide great reasons to honour queer legacies, but they’re hardly the end point for keeping queer stories alive, according to Baran, whose series continues this month with a screening of Death Becomes Her presented by the choreographer Raja Feather Kelly. In thinking about queer cultural history, he said, “We’re all on a continuum, and we need to understand it, and the only way we can understand it is to seek it out.”

And Thomas Beard, a programmer at large for Film at Lincoln Center who organised its 2016 series Queer Cinema Before Stonewall, cautioned against an emphasis on commemorating milestone moments.

“There are obviously many crucial episodes in the history of gay and trans liberation that predate Stonewall,” he said. “Our relationship to the historical past is never as neat as anniversary celebrations like these might suggest.”

“The horizon of true liberation still feels quite distant, though we still are struggling toward it,” he added.

© 2019 The New York Times