Artist David Hockney is the subject of a restored ‘pseudo-documentary’ from 1973 and a reissued French novel from last year. Can such semi-fictional accounts give us a real sense of an artist’s life and work? Deborah Solomon attempts an answer.

DO NOT TOUCH,” the signs admonish, reminding us that art museums are not petting zoos. They ask that we keep a respectful distance from the objects of our fascination. But still we seek to draw near, to step a little closer— not only to art, but also to the often-veiled lives of its creators. Luckily, bookstores and movie theatres have no such restrictions, and viewers intent on contemplating the dramas of the artistic life can always turn to biography.

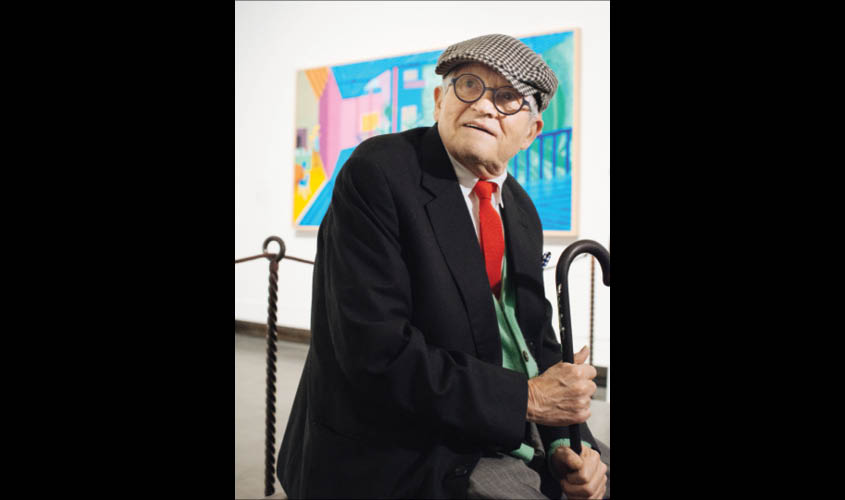

In an age when so many visual artists are mixing mediums, biographers, too, are blurring boundaries. On 21 June, A Bigger Splash, an entertaining pseudo-documentary on David Hockney made in 1973, will be released in a restored version that takes high definition to the higher yet altitude of 4K.

At the same time, Catherine Cusset’s short and stylish Life of David Hockney: A Novel, which came out in France last year, has now been published in English by Other Press.

The book’s title is a droll provocation, as well as a vexing self-contradiction. How can a book about an artist be both a biography and a novel at the same time? Cusset, a French novelist, had never met the artist when she sat down to muse on his interior life, and she made no attempt to contact Hockney, who will turn 82 on 9 July, and remains one of our most celebrated artists.

In reality, Cusset’s text is less subversive than her title. The book, which is lucidly written, adheres closely to the outlines of Hockney’s life. It tracks him from his boyhood in Yorkshire, England, with its sunless moors stretching in every direction, to his eager emigration, in 1964, to the squinty-bright landscape of Southern California. Inspired by the climate and views, he painted pool scenes whose sparkling planes of turquoise conjure a paradise untouched by time or decay.

Cusset’s tone is mostly laudatory. She sees Hockney as an iconoclast who has been forthright about his inclinations, depicting homoerotic scenes at a time when gay sex was still a criminal offense in England. She admires his steely work ethic and believes, behind his facade of good cheer and mismatched socks, his discipline is nearly fanatical. She is moved by his devotion to his churchgoing mother, whom he invites to London, puts up at the Savoy and takes shopping for a dress at Harrods.

As Cusset observes, “He was happy he could bring her such joy, his beloved mother whose daily life wasn’t easy, living with a silent husband who was more stubborn than a child, who did not regularly follow his diabetes treatment and ended up at the hospital once a month to be put on intravenous drip, indifferent to the concern he caused his wife.”

Cusset, of course, is hardly the first writer to fictionalise the life of an artist. It has now been exactly a century since the British novelist M. Somerset Maugham published his The Moon and Sixpence, which is probably the best-known book ever written about a painter. Its protagonist, Charles Strickland, is modeled on Paul Gauguin, the artist-stockbroker who had what we nowadays call “issues.” He abandoned his wife and children, moving into a squalid attic in Paris and living in penury before fleeing to Tahiti in the name of art with an uppercase A.

In the novel, Strickland is depicted as profoundly flawed. “He never said a clever thing,” Maugham writes, “but he had a vein of brutal sarcasm which was not ineffective, and he always said exactly what he thought.” The book was radical in recognising that artistic talent can be accompanied by a disturbing level of selfishness. Granted, the novel can seem dated in presenting the artistic life as a starkly binary choice between deranged genius and bourgeois contentment. It fails to notice that second-rate artists can be tormented, too.

Still, who can deny that novels about artists have certain advantages over straight biographies? While biographies routinely run to 700-plus fact-laden pages, a novel is more likely to be shapely in length. It will not waste your time with a dreary slog through a graveyard, which is how biographies traditionally begin, dutifully resurrecting long-forgotten ancestors whose relevance is not always clear. Moreover, a novel can offer an illusion of intimacy and lead you to dreamily think, “Here I am with Gauguin as he paces anxiously in his studio and wonders if that shade of orange is sufficiently bright.”

On the other hand, some of us turn to books less for escape than for critical analysis. And if you are reading for information, fictional biographies are obviously an inadequate form. As the biographer Robert A. Caro, speaking recently to writers and their supporters at a PEN American event, reminded us, “The more facts you come up with, the closer you come to whatever truth there is.”

The key word there is “closer,” because a biography, by definition, can never completely close in on every aspect of a life. It’s humbling when one tries to write a biography—when one confronts the gaping discrepancy between the ticking minutes of a lived life and the random piles of letters and articles, of airline tickets and other scraps of paper, that survive as documentation. A biography is a collection of puzzle pieces that do not fit, and the gaps can be as interesting as the connections. If you don’t like gaps, skip biography and read fiction.

Or create your own fiction. Cusset’s hybrid approach echoes that of the film A Bigger Splash. It, too, mashes up fact and fiction, intercutting documentary footage of the artist milling about his London studio with staged pool scenes that feel a little too eager to shock. Arriving just in time for the observation of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots, A Bigger Splash will open this month at the Metrograph, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, before rolling out to theaters across the country.

© 2019 THE NEW YORK TIMES