The 58th edition of the Venice Biennale, now open to the public, epitomises how conflicted today’s art world feels about financial concerns, with organisers making a conscious effort to dispel perceptions that it is a commercial event, writes Scott Reyburn.

The Venice Biennale, whose 58th edition opened to the public Saturday, is the world’s biggest and most influential survey of what artists currently make of the times we live in.

The event, lasting more than six months, and spread across the whole of this historic city, epitomises how conflicted today’s art world feels about financial concerns. For some, particularly in officialdom, “la Biennale” should have the commerce-free purity of a museum. “We must not fall into the trap of letting ourselves be guided by the market,” Paolo Baratta, the Biennale’s president, said last month in a statement. The Biennale, he added, should avoid being suspected of “compliance with selling strategies.”

For others, the event is also the world’s biggest art fair, if you just know whom and how to ask.

The main event, held in the Giardini gardens and the Arsenale, a former shipyard and arsenal, consists, as usual, of two elements. First, there is a sprawling international group exhibition, featuring a relatively pared-down selection of 79 invited artists or artist partnerships showing pieces in both the Central Pavilion in the Giardini and in the Arsenale.

This year’s chosen curator, Ralph Rugoff, director of the Hayward Gallery in London, has given the latest edition the enigmatic title, May You Live in Interesting Times. Second, there are contributions from 90 national pavilions.

This year, the organisers have made a conscious effort to dispel perceptions that the Venice Biennale is a commercial event. Labels in the main exhibition no longer credit the dealers who represent the selected artists. The temporary wooden walls constructed for the Arsenale group show have been left unpainted, to avoid it “looking too much like an art fair,” Rugoff said on a tour of the exhibition last week.

Over in the national pavilions, the helping hands of commerce are also well-hidden.

The United States is represented by African American artist Martin Puryear, whose powerfully meditative sculptures in different media on the themes of slavery and liberty are a contrast with the exuberance of America’s 2017 contribution by market star Mark Bradford.

Though Puryear had a solo show at MoMA in 2007, he is not particularly well-known internationally. Six months in the Venice spotlight will surely lead to a critical and financial re-evaluation.

But here, as well as elsewhere at the Biennale, art is discreetly available for sale. “We have placed some pieces, but we would be happy to sell others,” said Jacqueline Tran, a senior director of the New York and Los Angeles gallery Matthew Marks, which represents Puryear and is listed in the American Pavilion’s “Leadership Support” team. Tran added that the sculptures were priced between $1.5 million and $4 million.

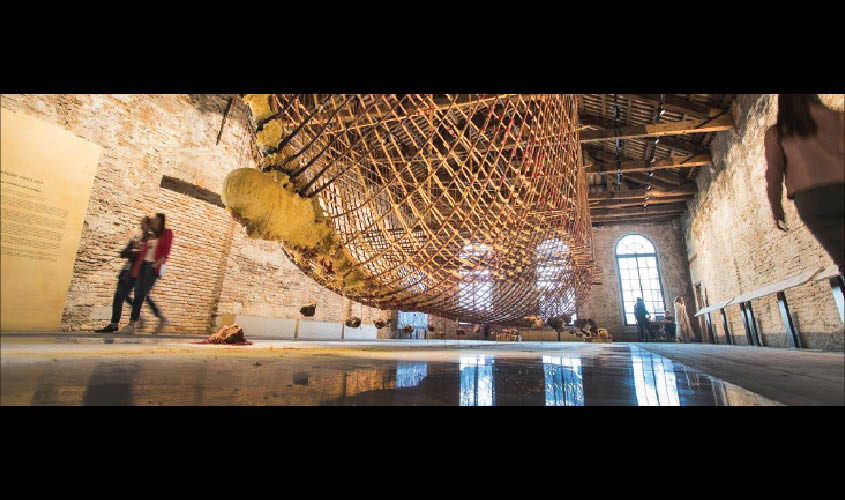

Ghana presented its first national pavilion at this Biennale, designed by the distinguished London-based architect David Adjaye. It displayed six presentations by artists that included internationally acclaimed names such as El Anatsui, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Ibrahim Mahama, as well as Felicia Abban, regarded as Ghana’s first woman to be a professional photographer.

Distinguished by the smell of smoked fish (incorporated in Mahama’s installation, A Straight Line Through the Carcass of History), and by the quality of the paintings, sculptures, photographs and videos on display, this is an exhibition where ostensibly nothing is for sale.

But during the four-day preview, when droves of museum curators and wealthy private collectors were in Venice, gallery staff members, such as Elisabeth Lalouschek, founder of the October Gallery in London, which represents El Anatsui, were available at the pavilion, as they were at many other national ones.

Anatsui first gained international fame at the 2007 Venice Biennale, when Belgian gallerist Axel Vervoordt audaciously draped a huge metal-foil cloth by the Ghanaian sculptor over the facade of the Palazzo Fortuny, like a gold tapestry ransacked from Byzantium. Three new, more-manageably sized cloths by Anatsui hang in the Ghana Pavilion. Prices for these now start at about $1 million, according to Giles Peppiatt, a specialist in modern and contemporary African art at Bonhams auctioneers in London.

Dealers were less in evidence at the Biennale’s international group show, but there was a tendency to display artists’ works in distinct groupings that at times resembled commercial gallery exhibitions. Five large paintings by Los Angeles artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby hung in a row at the Giardini, just as a show of her recent works was opening at the Victoria Miro gallery in Venice.

Museums are lining up to buy Crosby’s paintings, but prices for other artists could be obtained by email. Paris dealership Chantal Crousel quickly responded to a request for the cost of pieces by the technically innovative French sculptor Jean-Luc Moulène on show at the Giardini and the Arsenale. Donatrice, a 2019 work that places a battered 15th-century terra-cotta sculpture of a praying girl on a steel table, is priced at 135,000 euros, or about $152,000, she said.

The high proportion of known quantities (at least in the art world), such as Moulène, George Condo, Henry Taylor, Christian Marclay and Crosby, has led some to question just who and how much there is to discover in Rugoff’s selection of artists.

“It’s just all the hot stuff,” said Johann König, a Berlin dealer who represents Natascha Süder Happelmann, the selected artist at this year’s German pavilion.

Others approved of the curator’s selection. Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaundengo, a private collector with a foundation in Turin, Italy, said that 15 of the artists in the group show were represented in her own collection. “It’s a confirmation of the choices I made when I was supporting artists at the beginning of their careers,” said Sandretto Re Rebaundengo.

For her, this edition of the Biennale felt less commercial than others in recent years. “Art and the market are always connected, but maybe in the past there was too much of a market,” added Sandretto Re Rebaundengo, who noted that up until 1968, the event actually had its own sales office.

© 2019 The New York Times