Several developing countries view BRICS as an alternative to global bodies dominated by the West and hope that membership will unlock benefits such as development and increased investment.

London

‘The world is changing”, said South African President Cyril Ramaphosa at the opening of the plenary session of the BRICS summit on Wednesday. “New realities call for a fundamental reform of the institutions of global governance so that they may be more representative and better able to respond to the challenges that confront humanity”, he continued. Chinese President Xi Jinping added a couple of dramatic words declaring, “The course of history will be shaped by the choices we make”.

It has now been 14 years since BRICS was founded. The acronym, which did not originally include South Africa, was coined in 2001 by the then Goldman Sachs chief economist and later British government minister, Jim O’Neill, in a research paper that underlined the growth potential of Brazil, Russia, India, and China. South Africa joined the group after a Chinese-initiated invitation in 2012, a boost for the then President Jacob Zuma’s administration, which was eager to pivot further towards the east. The bloc also benefited from having a key African player and regional leader. Zuma was, however, jailed in 2021 for defying a Constitutional Court order to appear before a commission of inquiry investigating allegations

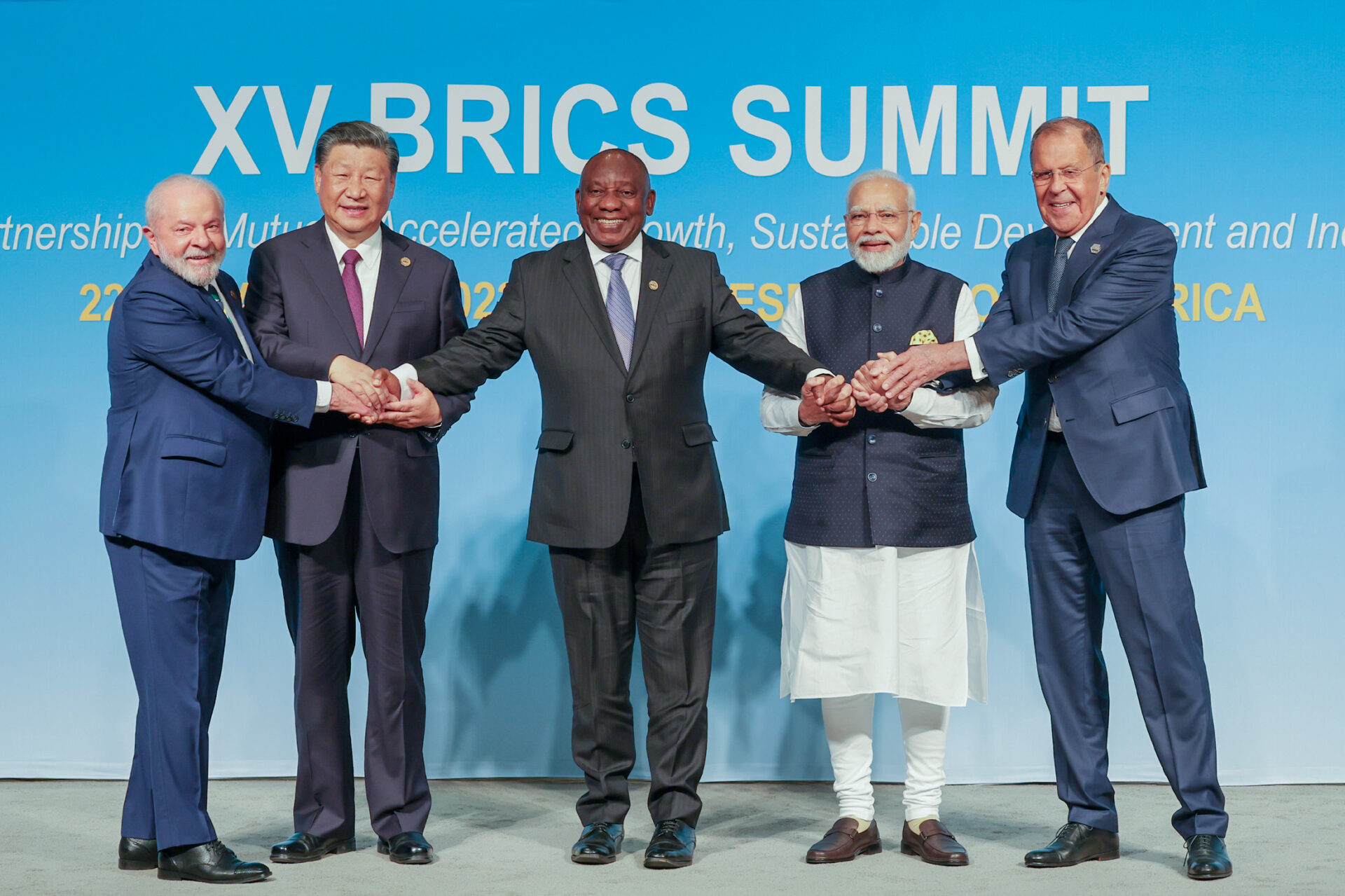

The group is not a formal multilateral organisation like the United Nations or World Bank, but an informal club where the heads of state and government of member nations convene annually, with each nation taking up a one-year rotating chairmanship of the group. This year was the 15th summit and South Africa’s turn to be host. It was planned to be the first face-to-face meeting at the highest level since the 2019 summit in Brazil, but President Vladimir Putin decided to attend virtually in order to avoid an International Criminal Court warrant for his arrest in connection with war crimes. In a 17-minute pre-recorded speech, the Russian leader criticised the impact of sanctions on his country because of the “special military operation”, which the majority of the world calls an invasion, and indirectly accused the West by tetchily criticising the “trampling of all the rules of free trade and economic life which we thought to be immovable before”.

The Chinese President was also absent from the beginning of the summit, even though he was in South Africa. No reason was given for this or why he did not give his opening speech, which was delivered by Chinese Commerce Minister Wang Wentao instead. China has long called for the expansion of BRICS as a means of fostering a multipolar world order to challenge Western dominance. “The world has entered a new period of turbulence and transformation”, claimed Xi in his speech on Wednesday. “We, the BRICS countries should always bear in mind our founding purpose of strengthening ourselves through unity”, he said, code for China, a dominant force in global economics as well as a growing military powerhouse, testing the limits of the United States’ influence.

The dominance of Washington and other Western powers was broached by India’s Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar at the earlier BRICS foreign minister’s meeting in South Africa on 1 June when he subtly described the current concentration of economic power as one that “leaves too many nations at the mercy of too few”. This is a sentiment that resonates across the developing world, where the United Nations Security Council’s veto-holding power remains limited to five nations based on an understanding rooted in 1945, at the end of World War II. Many have argued that India, now the most populous nation in the world, should immediately be added to the P5.

With the West’s footprint receding across the globe, the latest instance being in Niger and the Sahel, there is a growing chorus among Africa, Latin America, and emerging Asian powers like India to upend the post-Cold War unipolar system. Russia and China have pitched themselves as champions of this move away from a US-led order, whose rules, in the eyes of the Global South, Washington itself frequently flouts. There is certainly space for carving out a new world order, which has been created by not only the Global South finding its voice and looking for organisations like BRICS to champion its interests, but also by Russia and China finding themselves at odds with the West in an unprecedented way, largely because of the war in Ukraine. But “not so fast”, says India which does not view the voice of Beijing as a voice of the Global South. Instead, New Delhi appears to view China behaving like a developed country as trying to impinge on the narrative of the Global South.

Dissatisfaction with the global order among developing countries, exacerbated by Covid, when life-saving vaccines were hoarded by rich countries, has led to more than 40 countries expressing interest in joining BRICS. They represent a disparate pool of potential candidates, from Iran to Argentina, motivated largely by a desire to level a global playing field that many consider rigged against them. They view BRICS as an alternative to global bodies that are dominated by traditional Western powers and hope that membership will unlock benefits, such as development finance and increased trade and investment.

The debate over expansion topped the agenda at this year’s three-day summit. Uppermost in the minds of current BRICS members is that although they are home to about 40% of the world’s population and a quarter of global GDP, their economies vastly different in scale and have governments with often divergent foreign policy goals. This is a serious complicating factor for a bloc whose consensus decision-making model gives each member a de-facto veto. Additional members with divergent views and economies would only make decision-making even more difficult.

With this in mind, South Africa’s Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor on Wednesday said that BRICS leaders had agreed on mechanisms for considering new members. “We have agreed on the matter of expansion”, she told a radio station run by her ministry. “We have a document that we’ve adopted which sets out guidelines and principles, processes for considering countries that wish to become members of BRICS.” Officials said that India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, had proposed that of the 22 countries that had formally applied for membership, any successful country should not be the target of international sanctions. There should also be a minimum per capita GDP requirement.

News came on Thursday that the five BRICS nations would be expanded to eleven on 1 January 2024, the successful candidates being Argentina, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates. “This membership expansion is historic, a new starting point for BRICS cooperation”, claimed a delighted President Xi, “and will bring new vigour to the BRICS cooperation mechanism and further strengthen the force for world peace and development.”

Brazilian president, Luiz Inacio Lula de Silva, reminded the world that with the admission of six new members, the bloc would represent 46% of the world’s population and an even greater share of its capital output.

Russia, which enjoys support from its BRICS partners at a time of global isolation, was delighted with the outcome. Iran, of course, is a big supplier of drones and missiles to Russia for its war in Ukraine. South Africa, China, and India have not condemned Russia’s invasion, while Brazil has refused to join Western nations in sending arms to Ukraine or imposing sanctions on Moscow.

A big winner was China. The inclusion of Iran, strongly supported by China and Russia, has strengthened the anti-US axis in the BRICS, probably making it more antagonistic and challenging for the US and the West to deal with an organisation that contains two internationally sanctioned members. The decision to include Iran, a country with massive gas and oil reserves, also reflects the sway of China and Russia, which could not have been very comfortable for moderate members like Brazil and India. The fact that Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the UAE will be members was unthinkable until recently and indicates another facet of diplomatic reconciliation among the three countries, facilitated by China.

As for India, the timing of this year’s BRICS summit could not have been better for Prime Minister Modi. Nestled between his state visit to the United States, India’s G20 presidency, and the incredible success of the moon landing, Modi has used the global stage brilliantly in declaring and reinforcing India as the “voice of the Global South” and the new growth engine of the world. So, not only did the summit build BRICS bigger, but it built India bigger too.

John Dobson is a former British diplomat, who also worked in UK Prime Minister John Major’s office between 1995 and 1998. He is currently Visiting Fellow at the University of Plymouth.