Valmiki Faleiro’s book has intricate details the author gathered from 150 sources.

New Delhi

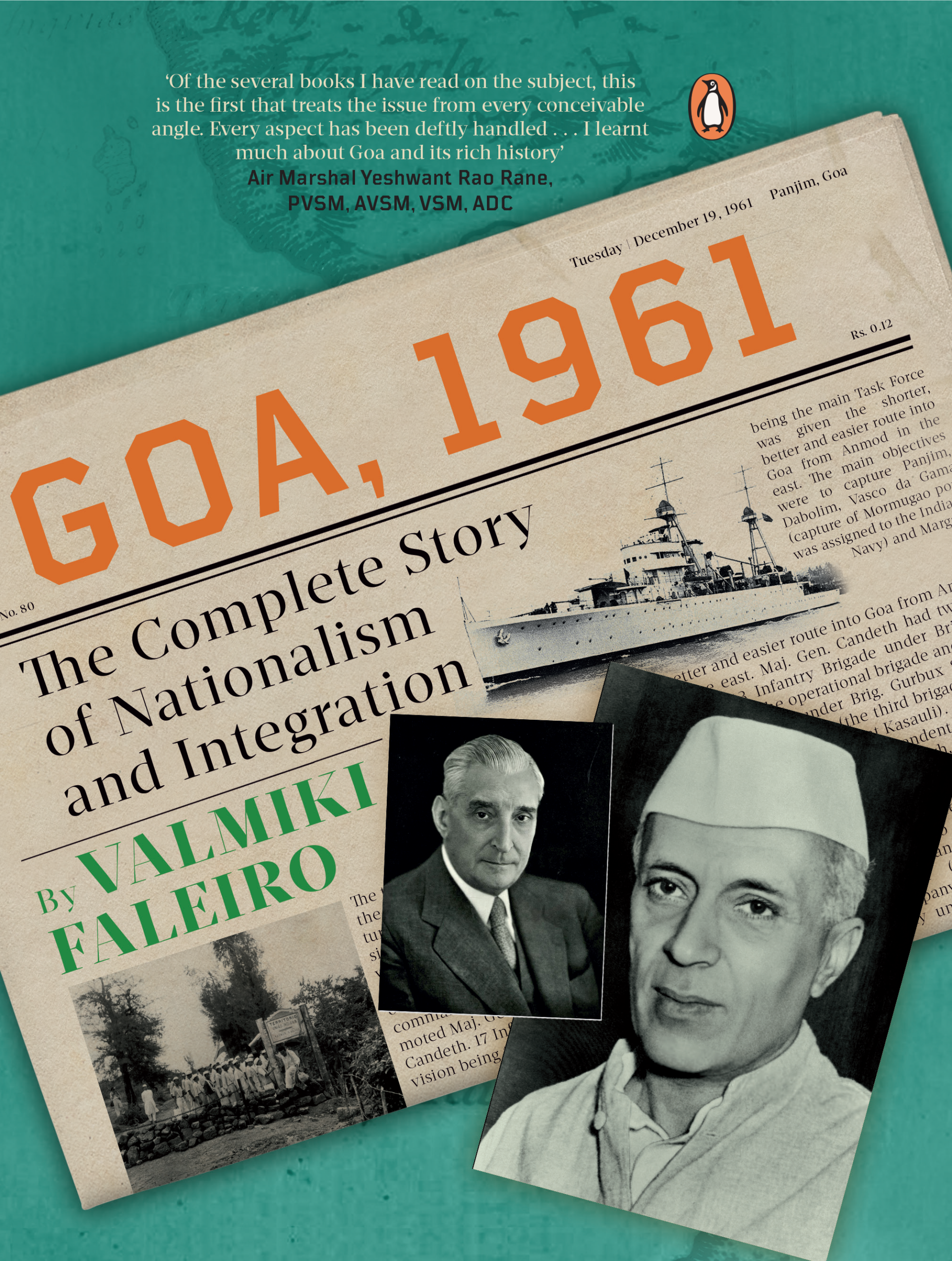

Like the big brushes of Maqbool Fida Hussain that filled giant canvases for the rich and famous, Valmiki Faleiro has filled up his latest book, Goa 1961: The Complete Story of Nationalism and Integration with some brilliant strokes.

It has intricate details the author gathered from 150 sources; the pages total 408. I am told the book is slowly, yet steadily, flying off the shelves across India, readers are loving it and not all of them are from Goa.

We are reading all about Goa’s liberation from Portuguese rule on 19 December 1961 after the 36-hour military intervention and then we are rummaging through some important facts that—typical of India—were buried deep in the dumps by historians. The historians will not tell you why they chose to ignore these important facts but we should not worry about the lapse, ostensibly because Faleiro—like a typical Indiana Jones—has found parts of the holy grail.

Let’s read through. Faleiro is ultra-cautious and plays it very safe when it comes to facts. And he keeps going back and forth, explaining every time the need to do it and why facts are very crucial for books of historical importance. He knows his subject, having written Patriotism in Action: Goans in India’s Defence Services and Soaring Spirit: 450 Years of Margao’s Espírito Santo Church 1565-2015. Now, unlike the previous one, this one is ideally written for the millennials. He has laced it with loads of narrative, developments and slices of emotions that liberated Goa from the clutches of the Portuguese.

Faleiro’s research is fascinating, else how on earth he would know that the Portuguese had an offer to sell Goa to the super-rich Nizam who had already planned to have a private seaport and add Goa as the third wing of Pakistan. And Transportes Aéreos da India Portuguesa (TAIP), a Goa-based civilian airline, started operating in 1955. It was the first civilian airline from India where airhostesses wore white saris as uniforms. They were fondly called white doves in Lisbon. The company had two de Havilland quad-engine Herons. Each aircraft could carry 14 fliers. And Goa’s first native Bishop Mateus Castro Mahale had masterminded an armed insurrection against the Portuguese way back in the 1750s.

Faleiro’s research showed it was an armed invasion by soldiers of the Indian Army who acquired notoriety for atrocities both before and after the 16 December military operation. On 19 December 1961, India announced Goa had been “liberated” from Portugal but Goans—after six long decades—have divided feelings about the operation. Probably, as the Supreme Court of India said on 9 August 1965, that Goa was “acquired by conquest”. The author says he would prefer to stay with both sides of the coin. Faleiro mentions it clearly how Jawaharlal Nehru is on record asking operations-in-charge, Southern Army Commander Gen J.N. Chaudhuri, for his conquest timeline (three days or less) on 24 October 1961. So, the PM knew and approved the invasion, right?

No wonder Faleiro severely criticises India’s poorly-thought-through seven-year economic blockade of Goa which backfired very severely. He says most Goans wanted amalgamation with India, an issue that was ignored, having anyway allowed them to hold two passports: Indian and Portuguese. That was not required. He blames Defence Minister Krishna Menon for messing up the show, along with Lt Gen B.M. Kaul, IG G.K. Handoo (for intelligence acquisition) and IB Director B.N. Malik.

Faleiro, I have a feeling, understands the core Goan character that stretches from resilience to adaptability, also fortitude against what the author claims was Portuguese repression. The author says with conviction that the euphoria of a victory against a NATO nation managed by Menon brought both success and victory for Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. The Congress registered political gains in the 1962 general elections, but was just not prepared for the 1962 Sino-Indian war and suffered a devastating blow.

Let’s return again to Goa, India’s smallest state that leads in indices of GDP, infrastructure and quality of life, thanks to its sun-kissed beaches and tourism sector. Faleiro brilliantly explains Goa’s history, especially how the Portuguese eastern capital shifted in 1530 to Cidade de Goa from Cochin. And then three coastal talukas were consolidated by 1543 that were called the Old Conquests. The author explains with loads of pain how majority inhabitants were repressively converted to the Christian Catholic faith.

What happened thereafter? The Portuguese—after 250 long years—amalgamated the remaining inland talukas through conquests but never bothered to convert the population, which remained primarily Hindu. The inland area was much larger and poorly connected, with poorer inhabitants. This, claims the author, is the reality which is at the heart of Goa’s Portuguese heritage. That is the best part of the book, it is full of facts—never mind if some of them are repetitive at times—and can be very handy for those interested in the story of Goa’s liberation.