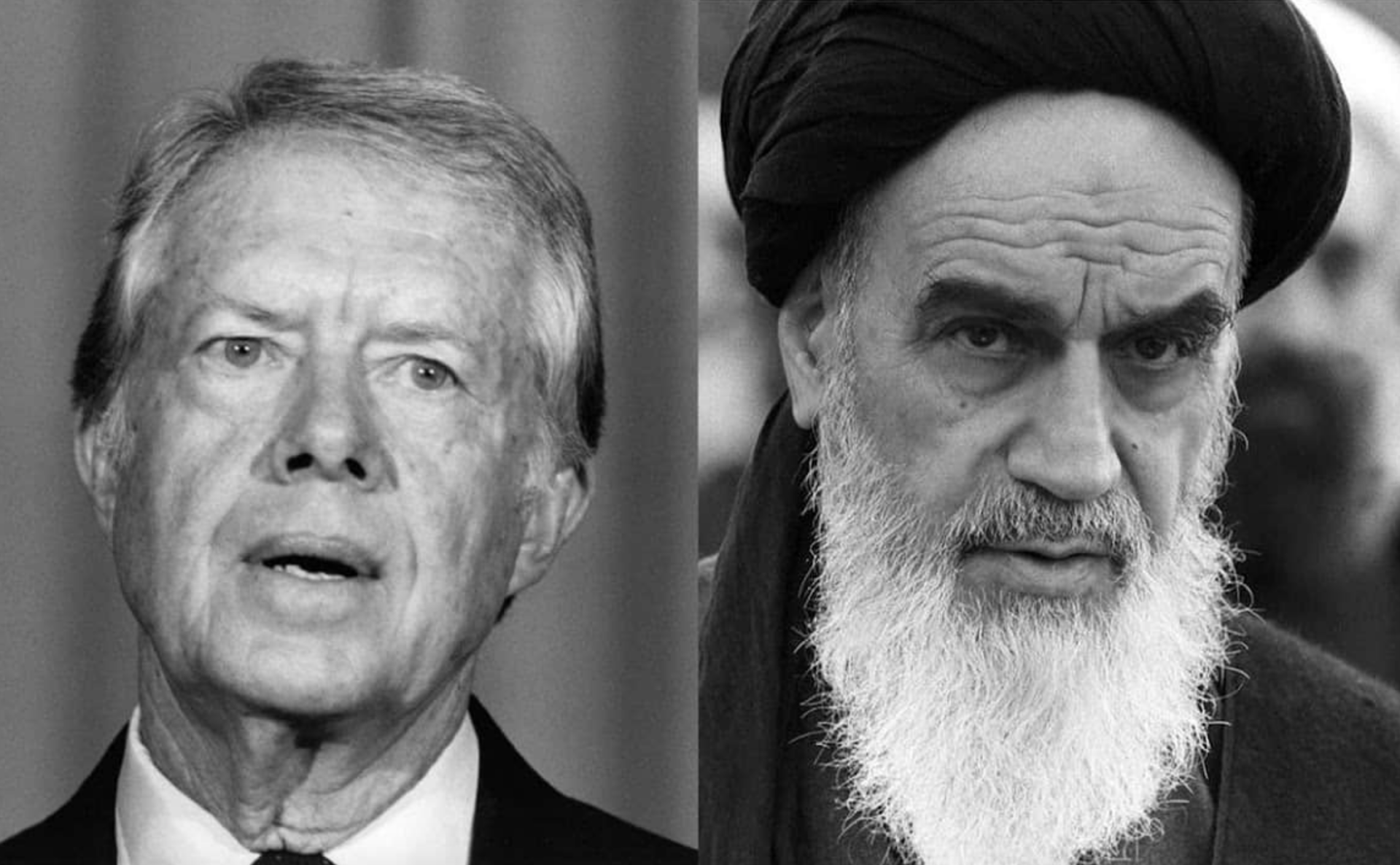

The story of how Iran went from a reliable pro-West ally to the center of fundamentalist terror begins with President Jimmy Carter, and his administration’s involvement in the Iranian Revolution.

November 4, 2023, marks the 44th anniversary of the Iranian hostage crisis.

It is a pivotal event along the path of Iran becoming the world’s primary supporter of Islamic terrorism. For 444 days, 52 Americans were imprisoned in brutal conditions.

The story of how Iran went from a reliable pro-West ally to the center of fundamentalist Islamic terror begins with President Jimmy Carter, and his administration’s involvement in the Iranian Revolution.

Islam’s three major sects, Sunni, Shiite, and Sufi, all harbour the seeds of violence and hatred. In 1881, a Sufi mystic ignited the Mahdi Revolt in the Sudan leading to eighteen years of death and misery throughout the upper Nile. During World War II, the Sunni Grand Mufti of Jerusalem befriended Hitler and helped Heinrich Himmler form Islamic Stormtrooper units to kill Jews in the Balkans.

After World War II, Islam secularised as mainstream leaders embraced Western economic interests to tap their vast oil and gas reserves. Activists became embroiled in the Middle East’s Cold War chessboard, aiding U.S., or Soviet, interests.

The Iranian Revolution changed that. Through the success of the Iranian Revolution, Islamic extremists of all sects embraced the words of Shiite Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini: “If the form of government willed by Islam were to come into being, none of the governments now existing in the world would be able to resist it; they would all capitulate.”

Dominance became an end in and of itself.

This did not have to happen.

Iran was a pivotal regional player for 2,500 years. The Persian Empire was the bane of ancient Greece. As the Greek Empire withered, Persia, later Iran, remained a political, economic, and cultural force. This is why their 1979 Revolution and subsequent confrontation with the U.S. inspired radicals throughout the Islamic world to become the Taliban, ISIS, Hamas, and others.

Iran’s modern history began as part of the East-West conflict following World War II. The Soviets heavily influenced and manipulated Iran’s first elected government. On August 19, 1953, British and American intelligence toppled that government and returned Shah Modammad Reza to power.

“The Shah”, as he became known globally, was reform-minded. He launched his “White Revolution” to build a modern, pro-West, pro-capitalist Iran in 1963. The Shah’s “Revolution” built the region’s largest middle class, and broke centuries of tradition by enfranchising women.

The Shah was opposed by many traditional powers, including fundamentalist Islamic leaders like the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Khomeini’s agitation for violent opposition to the Shah’s reforms led to his arrest and exile.

Throughout his reign, the Shah was vexed by radical Islamic and communist agitation. His secret police brutally suppressed fringe dissidents. This balancing act between Western reforms and control worked well, with a trend towards more reforms as the Shah aged. The Shah enjoyed warm relationships with American Presidents of both parties and was rewarded with lavish military aid.

That changed in 1977.

From the beginning, the Carter Administration expressed disdain for the Shah. President Carter pressed for the release of political prisoners. The Shah complied, allowing many radicals the freedom to openly oppose him.

Not satisfied with the pace or breadth of the Shah’s reforms, Carter envoys began a dialogue with the Ayatollah Khomeini, first at his home in Iraq and more intensely when he moved to a Paris suburb.

Indications that the U.S. was souring on the Shah emboldened dissidents across the political spectrum to confront the regime. Demonstrations, riots, and general strikes began to destabilise the Shah and his government. In response, the Shah accelerated reforms. This was viewed as weakness by the opposition.

The Western media, especially the BBC, began to promote the Ayatollah as a moderate alternative to the Shah’s “brutal regime”. The Ayatollah assured U.S. intelligence operatives and State Department officials that he would only be the “figurehead” for a western parliamentary system.

During the fall of 1978, strikes and demonstrations paralysed the country. The Carter Administration, led by Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and U.S. Ambassador to Iran William Sullivan, coalesced around abandoning the Shah and helping install Khomeini, who they viewed as a “moderate clergyman” who would be Iran’s “Gandhi-like” spiritual leader.

Time and political capital ran out. On January 16, 1979, the Shah, after arranging for an interim government, resigned and went into exile.

The balance of power shifted to the Iranian military.

While the Shah was preparing for his departure, General Robert Huyser, Deputy Commander of NATO, and his top aides, arrived in Iran. They were under Carter’s orders to neutralise the military leaders. Using ties of friendship, promises of aid, and assurance of safety, Huyser and his team convinced the Iranian commanders to allow the transitional government to finalise arrangements for Khomeini becoming part of the new government.

Subsequently, many of these Iranian military leaders, and their families, were slaughtered. Khomeini and his Islamic Republican Guard toppled the transitional government and seized power during the Spring of 1979. “It was a most despicable act of treachery, for which I will always be ashamed” admitted one NATO general years later.

The radicalisation of Iran occurred at lightning speed. Khomeini and his lieutenants remade Iran’s government and society into a totalitarian fundamentalist Islamic state. Anyone who opposed their Islamic Revolution were driven into exile, imprisoned, or killed.

Khomeini’s earlier assurances of moderation and working with the West vanished. Radicalised mobs turned their attention to eradicating all vestiges of the West. This included the U.S. Embassy.

The first attack on the U.S. Embassy occurred on the morning of February 14, 1979. Coincidently, this was the same day that Adolph Dubs, the U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, was kidnapped and fatally shot by Muslim extremists in Kabul. In Tehran, Ambassador Sullivan surrendered the U.S. Embassy and was able to resolve the occupation within hours through negotiations with the Iranian Foreign Minister.

Despite this attack, and the bloodshed in Kabul, nothing was done to either close the Tehran Embassy, reduce personnel, or strengthen its defenses. During the takeover, Embassy personnel failed to burn sensitive documents as their furnaces malfunctioned. They installed cheaper paper shredders. During the 444-day occupation, rug weavers were employed to reconstruct the sensitive shredded documents, creating global embarrassment of America.

Starting in September 1979, radical students began planning a more extensive assault on the Embassy. This included daily demonstrations outside the U.S. Embassy to trigger an Embassy security

On November 4, 1979, one of the demonstrations erupted into an all-out conflict within the Embassy’s visa processing public entrance. The assault leaders deployed approximately 500 students. Female students hid metal cutters under their robes, which were used to breach the Embassy gates.

Khomeini immediately issued a statement of support, declaring it “the second revolution” and the U.S. Embassy an “American spy den in Tehran”.

What followed was an unending ordeal of terror and deprivation for the 66 hostages, who through various releases, were reduced to a core of 52. The 2012 film “Argo” chronicled the audacious escape of six Americans who had been outside the U.S. Embassy at the time of the takeover.

On April 24, 1980, trying to break out of this chronic crisis, Carter initiated an ill-conceived, and poorly executed, rescue mission called Operation Eagle Claw. It ended with crashed helicopters and eight dead soldiers at the staging area outside of the Iranian capital, designated Desert One. Another attempt was made through diplomacy as part of a hoped-for “October Surprise”, but the Iranians cancelled the deal just as planes were being mustered at Andrews Air Force Base.

Carter paid the price for his Iranian duplicity. On November 4, 1980, Ronald Reagan obliterated Carter in the worst defeat suffered by an incumbent President since Herbert Hoover in 1932.

Unfortunately, the world continues to pay the price for Carter unleashing Khomeini as the ruler of Iran.

Scot Faulkner served as Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. He was Director of Personnel for the 1980 Reagan Campaign, served on the Presidential Transition team, and on Reagan’s White House Staff. He currently advises corporations on implementing strategic change.