NEW DELHI: It does not have a defined military rival, but it has a history of violent coups and now the role of the Bangladesh Army seems more questionable than ever.

Two big questions remain unanswered after the ouster of Sheikh Hasina as the Prime Minister of Bangladesh—how much of the Bangladesh Army and allied armed forces have been infiltrated by Islamists, and what is the scale of assets that the Bangladesh Army and other armed forces own?

These two questions have always hung heavy over the body polity of Bangladesh ever since its very creation. During the 1971 liberation war, which broke away East Pakistan and created Bangladesh, the Bengali soldiers in the east revolted against their west Pakistani commanders and fought the Pakistani Army from the west to push through the cause of independence, fighting side-by-side with civilian revolutionaries, but from the moment independence came, the friction between the civilian leadership and the army was relentless.

It was blood-soaked army coups that eliminated Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, popularly known as Bangabandhu or the Friend of Bangladesh, and the father of the Bangladeshi nation, with his entire family, barring two daughters who were outside Bangladesh in August 1975; and in 1981, a general who was a participant in earlier coups, and had managed to rise to become the President of Bangladesh, Ziaur Rahman, was himself murdered by a different faction of the armed forces. Between 1983 and 1990, the country was ruled by a military dictator, General Muhammad Ershad. In 2011, another faction of the Bangladeshi armed forces, with a stated desire to establish Islamic law in Bangladesh, revolted and attempted a coup. This came only two years after another murderous revolt by a faction of the Bangladesh Rifles, the country’s border security force.

In each occasion, there have been questions on the real motive of the coups and attempted coups, how much of these were power grabs, and what portion was driven by extremist religious ideology. In 2008, writing for the Harvard International Review, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, the US-based technology evangelist businessman and consultant, and son of Sheikh Hasina, pointed out that military recruitment in Bangladesh used to have around 5% recruitment from the Islamist groups’ young foot soldiers, but this had gone up to around 35%. As the son of Sheikh Hasina, who was firmly against groups like the Jamaat-e-Islami and pushed the trial of Islamists for siding with Pakistan and participating in war crimes in the 1971 war, Sajeeb Wazed Joy’s assessment could be tempered down for bias, but as the 2011 coup attempt showed, Islamist ideology was prevalent enough within the armed forces to embolden a conspiracy for a coup to capture control of the army and the government.

While ideology remains a virulent problem in Bangladesh, there are deeper existential questions about the Bangladeshi military. Unlike India or Pakistan, Bangladesh, with nearly 200 million people, does not have a direct military rival threatening it. It has no critical militaristic challenge and yet the Bangladesh Army, born as it was as an offshoot of the Pakistan Army, has always had expansionistic tendencies. The only country in the Indian subcontinent which has a much more aggressive history of military interference in civilian government is the Pakistan Army, which is widely considered the real seat of power in that country which has often disrupted civilian rule with military coups. The Bangladesh Army, in a sense, has tried to follow suit. There has never been a period in the history of Bangladesh when its government has not had some kind of overhang from the armed forces. The memory of the assassination of Mujibur Rahman and his family, including his young children, by officers of the armed forces still casts a shadow on civilian government-military relations in the country, not least because it is widely known that Mujibur Rahman had been warned by Indian intelligence agencies that a coup was being plotted against him, and that he should leave the country with his children. But he refused arguing that his “own people” would never harm him.

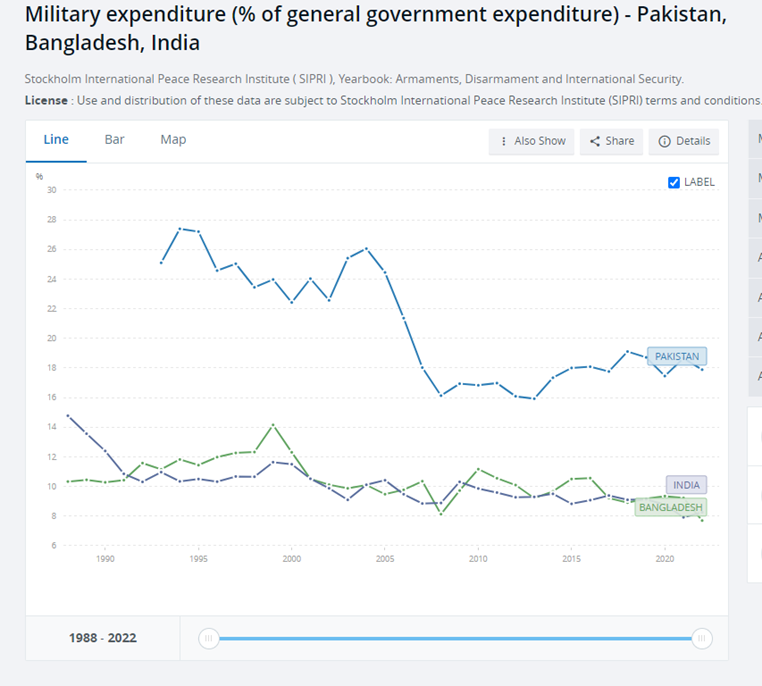

In fact, apart from Sheikh Hasina and the Islamists, there are few prominent national leaders in the history of Bangladesh who were not generals and rose to power via coups and authoritarian measures. Hasina’s fierce rival, Khaleda Zia, is the widow of Ziaur Rahman, the general who became President through a military coup. This is why the military, despite its lack of war challenge, has received significant support through its history in Bangladesh; for instance, as the accompanying graph shows, despite being a fraction of India’s size and for most of its history relatively much poorer, military expenditure as a percentage of government expenditure in Bangladesh closely mapped India’s trajectory, sometimes even superseding India.

Even though the Bangladesh Army has never fought a major war—unlike the Pakistani Army—in the Global Firepower Index (2024), which assesses military strength, its “military strength values” are higher than that of Pakistan. The Index ranks the Bangladesh Army at 43, while the Pakistan Army is ranked four notches below at 47.

Hasina, on her part, while doggedly pursuing legal action against the killer of her family, had also tried the appeasement route towards the military. Under her watch, the Bangladesh Army Welfare Trust (modelled after the Army Welfare Trust and Fauji Foundation of Pakistan) and other organisations (sort of holding firms) like the Sena Kalyan Sangstha grew to run a whole range of commercial activities which have an estimated combined turnover of nearly $1 billion. It runs a bank, major cement companies, textile mills, shopping complexes, a clutch of hotels, gas stations, and a golf club, and even a major ice-cream company, among many other assets.

Also supported by Hasina, the Bangladesh Army developed an ambitious expansion plan called Forces Goal 2030 which was rolled out around 2017. As the Bangladeshi military analyst Iqram Hossain Mahqoob has written, the army under Hasina received support to grow at an “unprecedented” level, which involved: “… the raising of three full Infantry divisions (7, 10, and 17), engineer construction battalions, armoured regiments, and establishing brigades (a tactical formation of the Army), where eight infantry battalions (a tactical group lower than brigades) and one infantry brigade have been mechanized. In recent years, the number of cantonments has also been increased. The army has already made a number of upgrades to its equipment, including the procurement of helicopters, unmanned planes, and anti-aircraft missiles, in accordance with the strategy. Many of these transactions used Chinese equipment: Bangladesh has ordered 36 WS-22 multiple rocket launcher systems (MRLS), 44 MBT-2000 Main Battle Tanks, two regiments of FM-90 short range surface to air missiles, QW-2 and FN-6 hand-held anti-aircraft missiles, and PF-98 anti-tank rockets.”

Perhaps even more elaborate, and certainly more eyebrow-raising (from the perspective of both America and India) developments took place in the Bangladesh Navy. Mahqoob notes, “The Navy has seen a major increase in firepower and weapon production capabilities. Over the past 14 years, the Navy’s Fleet has grown by 31 vessels, including four frigates, six corvettes, four big patrol craft, five fuel craft, and two training ships, transforming it into a fully operational three-dimensional force. Two new Chinese built submarines, two corvettes, and a number of patrol boats have been delivered to the Bangladesh Navy. In order to provide secure jetty facilities for submarines and warships in the harbour, Bangladesh is getting ready to operationalize its first submarine base with modern basin facilities for the Navy at Pekua of Cox’s Bazar. Also, a new naval base (BNS Sher-e-Bangla) in the Bay of Bengal will be able to offer maritime and coastal defence, air support for the seaport and the communities around it, and defence against external enemy attack.”

Not to be left out, the Bangladesh Air Force also received, under this expansion plan to 2030, “…23 PT-6 basic trainers, 16 Chengdu F-7BGI fighters, 16 Yakovlev Yak-130 advanced jet trainers, 9 K-8W jet trainers, 3 Let L-410 Turbolet transport trainers, and 16 Yakovlev Yak-130 advanced jet trainers. The Force is poised to acquire high-performance, ultra-modern fighter planes”, says Maqoob, under this plan which had been signed off by Hasina.

There was speculation that Hasina, who had never quite trusted the army after the role its members had in the decimation of her own family, including the assassination of her father, wanted to ensure that the armed forces get the financial support they need so that their loyalty to her government, and to her, at a personal level, was not questionable. The appointment of General Waqar uz-Zaman, as the army chief, who is the husband of a cousin of Sheikh Hasina, was meant to further strengthen ties between Hasina and the army so that any fissures could be tackled swiftly and without any errors.

But when the mob started towards Ganabhaban, the residence of the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Army gave Hasina barely 45 minutes to pack up and exit the country. Reportedly, Hasina was furious that the army would not protect her with greater force. There is also speculation that without the army’s tacit support, the interim government could not have been formed after Hasina left (she is now in exile in India). And the returning any semblance of peace on the streets of Bangladesh, required, and will require the firm hand of the army (especially since the police force has been decimated and is still seen as loyal to Hasina) for the interim government led by the banker Muhammad Yunus to operate. But will Yunus—seen as the favourite candidate of the Western world, especially America—be able to give the army further financial

And finally, it is a rather large question mark on what part of the Bangladesh Army is loyal to the cause of establishing Islamic rule in the country and how will that faction play out in the future.

Hindol Sengupta is professor of international relations at O. P. Jindal Global University, and co-founder of the foreign policy platform Global Order.