Tokyo

The mission reflects the ethos of America, especially parts of Silicon Valley history, parts of Japanese history, and indeed a long history of Indian diasporas that departed from and arrived at India in different times.

It was 1 October 1787, soon after the American War of Independence from Britain, April 1775 to September 1783, that left seething anger among the British that spilled over into attempts to wreck the fledgling nation’s trade and investment. It was then believed in the British Royal Court that the US experiment with democracy would fail and the former colonies would come begging to rejoin the British Empire. America was highly indebted as a percentage of GDP after defeating the world’s then-leading superpower. Therefore, in order to break the British trade stalemate or embargo and to establish a presence in the Pacific, American pioneers set out in two ships, The Lady Washington a sixty-foot single masted sloop with eleven men (partly financed by Martha, the wife of General George Washington) and the Columbia Rediviva, an 83 feet three-masted brig with a captain and crew of 40 sailors. This fascinating story is told by Historian Scott Ridley in his book “Morning of Fire: America’s Epic First Journey into the Pacific” (Reference 1) as well as other historians referenced in this article, and in historical records and documents, now located in museums in the US and Japan. It is a Trans-Pacific story in pursuit of capital for the then-fledging new nation’s development to sustain independence and freedom.

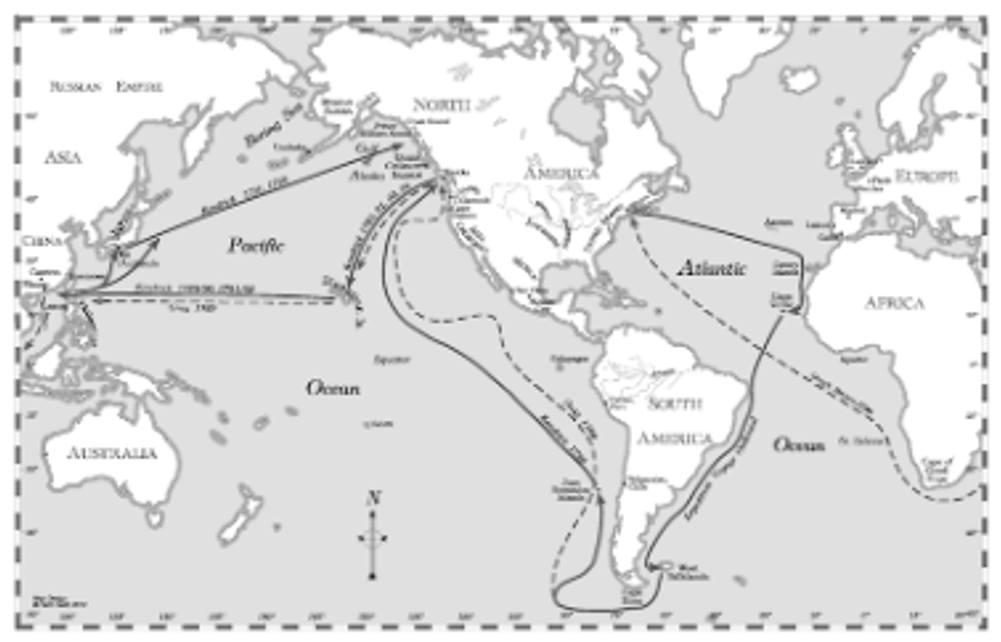

At the time, over a century before the Panama Canal, ships sailing from Boston had to go around Cape Horn, southern tip of South America, before heading towards Asia. Commanded by Captain John Kendrick, who had been a whaling captain, a sea captain during the American Revolutionary War and a Privateer (officially sanctioned by the new nation to attack and take ships at sea) and therefore a war hero who had with another captain captured two British merchant vessels for which King Louis XVI of France had awarded the duo 400,000 French livres (French currency until 1794) in exchange for the prize ships that carried muscovado sugar (mineral-and-molasses-rich brown cane sugar) and rum from Jamaica to London. It is even hypothesized that the desire to take the ships among King Louis’ ministers made France to move from “neutral” to the side of the revolutionaries. Such stories of his daring escapades circulated through the social media of that era and some of the founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams and indeed George Washington, knew Kendrick.

Captain Kendrick was one of the “Sons of Liberty” who boarded two ships of the British East India Company and threw 342 chests of highly taxed “British” tea (in truth exported colonial Indian tea) overboard on the rainy, dark night of 16 December 1773 while dressed as native Americans, an action later dubbed the “Boston Tea Party”. (Reference 2)

Later, after the outbreak of hostilities with Britain, in May 1776 Kendrick was believed to have smuggled arms including muskets and cannon & pistol gunpowder from the Caribbean on board a vessel whose owners were under contract with a secret committee of the Continental Congress (the interim parliament of the government-in-exile of the breakaway nation).

Once the war was over, the American economy was in a shambles and it faced great hostility from Britain that blocked its access to ports it controlled in Canada, the Caribbean and in Europe. The British armed forces had seized hundreds of ships belonging to Americans, either burned them where they were anchored or auctioned them in Liverpool, and devastated Boston and most port cities on the Atlantic Coast. Other European powers, France and Spain, wanted exclusivity on trade over the newly independent colonies, and so there was no easy solution to the trade and investment imbroglio.

It was then that a group of financiers led by Joseph Barrell, a member of a large Boston merchant family, dreamed up the visionary, risky voyage costing $49,000 in year 1787 dollars (about $1.7 million today) and mission to the Pacific (today the Indo-Pacific) to establish a permanent American presence. In part, this voyage was inspired by Captain Cook’s journal of his 1776-1780 third voyage to the Pacific, when Cook recorded that he bought rich furs in exchange for trinkets from Northern Pacific Coast native Americans and sold each of those sea otter pelts in China for as high as Spanish dollars 120—more than double the annual wages of a seaman. Fashionable women in cold Imperial China were keen to have those fur coats and the trade promised rich returns for the infant nation.

The financiers included Charles Bulfinch, later to become America’s most prominent architect who had toured Europe after university studies and counted Thomas Jefferson, also an architect among multiple renaissance skills, as his mentor, who then was US Minister to France in Paris. Bulfinch may have helped to get the official letter of support for the mission from Thomas Jefferson.

Others included Crowell Hatch, a Boston captain, Samuel Brown, a Boston merchant and shipowner, John Derby, a Salem merchant whose family owned and provisioned ships, and John Pintard a New York financier.

Barrell took approximately 28% of the equity (buying 4 out of 14 shares) and the others took two shares each (approximately 14%). They offered overall command of the expedition to Captain Kendrick who added insight, vision, conviction and experience to the plan, which built the entire team’s confidence in successful prospects. Leadership assistance for the second ship was assigned to Captain Robert Gray.

The team sent New York merchant John Pintard, who had been active in the China and East India trade, to seek a Sea Letter from the Congress of the Confederation, an official document to ensure safe passage and protection in international waters, which they secured on 24 September 1788, approved by the 28 Members. It was a ribboned document, embossed with the seal of the Congress, and signed by Arthur St. Clair, who presided over the Chamber. It was addressed to kings and officials of foreign ports and placed the ships under the patronage and protection of Congress.

Nevertheless, the ships also had cannons and swivel guns for protection. It was known that around 25% of the crew would succumb to diseases like scurvy on a long two-year voyage, and huge amounts of provisions would be required as well as massive quantities of trade goods and ship maintenance materials. Interestingly, mortality on this mission was reduced to only one sailor by careful public health measures.

The trade vision was to secure sea otter pelts and sealskins from native Americans in exchange for trinkets, take them to Macao and exchange for tea, silk, porcelain and other goods. The voyage was reported in Boston and other newspapers.

MACAO

Silk-robed mandarins (Imperial Chinese bureaucrats) and large numbers of customs officials and soldiers managed the heavily bureaucratized port of Macao, the sole Chinese port open to foreigners. Portugal held formal ownership of Macao since 1557 but the Chinese viceroy at Canton and resident mandarin wielded real power. Further, the Chinese Emperor claimed sovereignty over all things under heaven in the “Celestial

Kingdom”. Many foreign captains believed that a bureaucratic nightmare was deliberately created at Macao in order to extract tributes and gifts for Chinese merchants and officials. Kendrick’s first application to trade the cargo he was carrying was denied.

Kendrick’s cargo of 500 sea otter pelts and sealskins was worth approximately $233,000 in today’s currency. Yet he was expected to give port charges of $127,000 plus a tip or cumshaw of $85,000 in today’s currency. Further, since the Chinese government had given virtual monopoly over trade to 12 brokers who insisted on cargo being made over to them before them acting, foreign captains felt that smuggling was a better option. Also, Kendrick did not apply for a permit to go beyond Macao upriver to Canton, and instead went overland to Canton after dropping anchor at Dirty Butter Bay. Regrettably for Kendrick, he was spotted and arrested, and not having sufficient funds to secure his freedom had to serve his term after which he was under strict injunctions never to return to China.

JAPAN

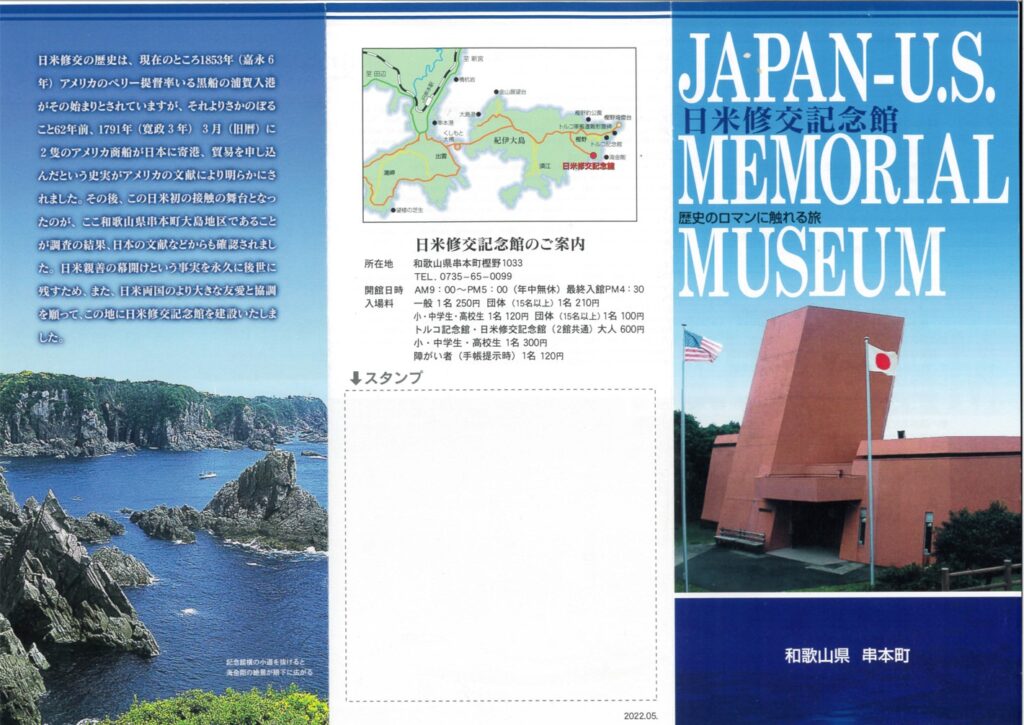

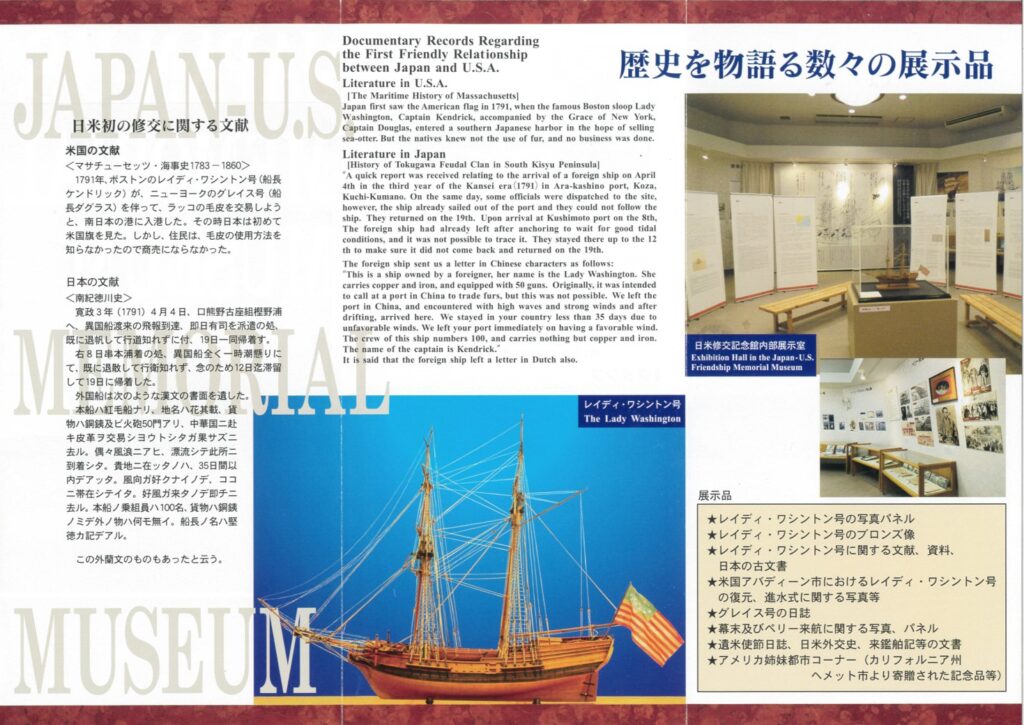

Kendrick was therefore looking for a market alternate to Canton, when gossip on the waterfront pointed to a rich market existing in Japan, but which was under strict exclusionary rules of the Tokugawa Shogunate (military government) with the sole port open to foreign trade being Nagasaki that was controlled by the Dutch. Kendrick did not want to go to Nagasaki for fear of being branded and betrayed as an interloper by the Dutch. Captain Kendrick, a master navigator, piloted The Lady Washington into Kushimoto harbour in Wakayama Prefecture in May 1791. He had wanted to go to Sakai or Osaka near the Imperial capital of Miyako (old name of Kyoto) but believed that the rip tides that race through the narrow straits on either side of the Awaji island would be too dangerous for his relatively small ship.

All books and reports point to Kendrick having had to face and overcome an unusually large multitude of challenges ever since he set out from Boston—in virtually every port, on the high seas, and even on the ships he commanded. But his choice of landing in Wakayama Prefecture for nautical reasons, was perhaps the most erroneous for geopolitical reasons (Reference 3). That is because the Kii branch of the Tokugawa

family was ruling Wakayama and it was the most hostile to foreign involvement except the Edo (Tokyo) branch itself and was among the very few clans that could supply a future Shogun other than the Tokyo branch of the Tokugawa family.

Kendrick made several errors in the eyes of the Shogun’s officials. First, he did not observe the fine courtesy

expected of foreigners and meticulously followed by the Dutch in Nagasaki. The bureaucrats rushed to judgment that Kendrick lacked etiquette and therefore was remiss in social graces. Further, Kendrick, accustomed to commanding ships and men, did not defer to the Japanese officials, something they were accustomed to from foreigners. But the greatest blow to Kendrick came when the Japanese understood that

his cargo was not silks, aromatic sandalwood or sugar, but rather otter pelts and sealskins for which they had little use at the time, and it further associated Kendrick in the eyes of the officials with low social standing for that was the perception then of those who worked with animal skins.

Kendrick was also stymied by his lack of knowledge of Japanese or Dutch or even of Chinese written script

that might have enabled the officials to understand the subtlety of what Captain Kendrick was attempting

to communicate.

Ironically, Kendrick did have the sandalwood that the Japanese desired until he left Macao en route to Japan—he had successfully opened the sandalwood trade with Hawaii. However, he had disgorged that cargo to Captain James Douglas of the New York Sloop Grace while in Macao. It was a case of Murphy’s Law of everything that could possibly go wrong indeed happening: a haughty captain sailed with an

undesired cargo into the worst port of an unwilling empire. Yet many reports also point to Kendrick managing to wriggle out of tricky or risky situations with his strategic thinking and “spin”. A rare American document with a first person account containing a day-by-day record of Kendrick’s 10-day visit to Japan was discovered through research by historical societies in Wareham, Massachusetts and Kushimoto, Japan.

At the end of the visit, however, Captain Kendrick was asked to leave, by the Shogun’s officials who ordered their guard boats to tow him out to sea with added warnings not to return to the forbidden waters of Japan.

WHY REMEMBER CAPTAIN KENDRICK AND HIS MISSION TO JAPAN?

Since Captain Kendrick’s 1791 mission to Japan itself was unsuccessful to open American trade to Japan, even though historians agree that he was the first American with official papers to make landfall in Kushimoto, Japan, and display the American flag, the Stars and Stripes (Reference 4), his pioneering effort received less attention than that of Commodore Perry’s some 60 years later. But success and failure are often just processes in the continuity of life.

Kendrick was, in effect, the first American true globalist, equally comfortable in tropical waters such as in Cape Verde (where he extended his stay to 41 days since it appealed to him) or indeed in Hawaii and broadly circumnavigating the globe especially in the Indo-Pacific searching for and attempting to open new markets for his newly independent nation.

The mission reflects the ethos of America, especially parts of Silicon Valley history, parts of Japanese history, and indeed a long history of Indian diasporas that departed from and arrived at India in different times, where a small group of insightful, determined investors pooled capital according to agreed

percentages and associated rules, put that capital to every type of risk—geopolitical, currency convertibility, piracy, diseases, breach of contract, civil wars, national security and yet often came out ahead with financial and other returns that sustained their investment activity while enabling trade and investment links across continents, technologies, markets, and very diverse peoples. This is profoundly different from appealing to shrinking pools of government capital, often associated with cronyism for public resources. It is that spirit

of unbounded frontier enterprise that separated the newly independent nation from its colonial past that reflects what Captain Kendrick and those who financed his mission represented. While profits of these missions were moderate in the initial years, they proved to become the standard route for vigorous and profitable US-Far East trade. In its own way, Captain Kendrick’s was a pioneering American success story.

Therefore, it is time that Captain Kendrick is given his due recognition with an annual investment conference with primarily private investors from the US-Japan and partner countries like India, ASEAN nations, with operational and research teams like what Kendrick assembled to carry out the mission. Over time, the US and Japan became among the greatest trading and investing nations. Today, with many voicing concerns about globalization beset by increasing inequality, it is time to find ways to utilize the investment

ethos of Captain Kendrick and his teams, non-officials and ordinary people seeking a better trade and investment tomorrow, to chart a new path-breaking future for capital and opportunity for all.

REFERENCES:

1) Ridley, Scott (2011). Morning of Fire: John Kendrick’s Daring American Odyssey in the Pacific. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0061700194

2) Capistrano-Baker, Florina H.; Priyadarshini, Mesha (6 September 2022). Transpacific Engagements: Trade, Translation, and Visual Culture of Entangled Empires. Getty Research Institute. p. 230. ISBN 978- 6218028258.

3) Wildes, Harry Emerson: “Aliens in the East”. University of Pennsylvania Press. 1937.

4) Sayama, Kazuo: “Wagana wa Kendrick (My Name is Kendrick)” Sairyusha Co., Dec. 2009. ISBN 978-

4779114892.

Dr Sunil Chacko holds degrees in medicine (Kerala), public health (Harvard) and an MBA (Columbia). He was Assistant Director of Harvard University’s Intl. Commission on Health Research, served in the Executive Office of the World Bank Group, and has been a faculty member in the US, Canada, Japan and India.