Bali, a sub-tropical Indonesian island in the southern hemisphere, conjures up an air of idyllic, ancient mystique, reaching back in time for its wellsprings. While forming part of the Dutch East Indies, it was fabled in the colonial world for its beautiful bare-breasted women. There are myriad representations of those proudbreasts, expressive eyes, hand mudras, svelte bodies swaying to lute-like music.

This alluring image was progressed considerably by 19th century European painters and artists, adventurers who landed in Javanese Malang, or Balinese Denpasar, after the Dutch invasion of 1906. Many stayed on, marrying their Balinese muses, immortalising their beauty, extolling the virtues of the simple way of life.

And there was also the hit Broadway musical South Pacific, with its Rodgers and Hammerstein composed show-tune Bali Hai—the mystical but unreachable island on the horizon. This Bali Hai had nothing at all to do with the Indonesian island of Bali, but it didn’t stop it being associated; and for the thousand restaurants, spas, and cocktail bars it spawned around the globe, all using the name.

And then there was the famous Dutchwoman, an adoptive Balinese who learned its dance techniques, and captured the imagination of the world. And whose varying legend spawned a host of movies and plays, over the years since World War 1. Mata Hari (Eye of the Dawn), with her invented Hindu princess back-story, went from captivating young woman in the Netherlands to promiscuous wife and mother in the Dutch East Indies. And later still, after her divorce, she became an exotic dancer in Paris, then a courtesan turned enigmatic spy and double-agent between France and Germany. She was, in the end, allegedly scapegoated and betrayed by her friends in high places, including the heir to the Kaiser; and eventually executed at 41 by the French. Mata Hari’s highly publicised career as a femme fatale and its denouement only added poignancy to her association with the “Great War to end all Wars” and furthered curiosity about Bali.

Today, Indonesia is vibrantly independent and the Ramayana and the Mahabharata are alive and well in Bali. The epics, on the shelf in India, are unabashedly read and idealised there. They are known, reverentially regarded, but form part of the common folklore too. This, alongside Hindi films and serials from far away India and swarms of Bintang (Balinese beer) swilling Australian tourists, from just 3 to 5 hours’ flight-time away.

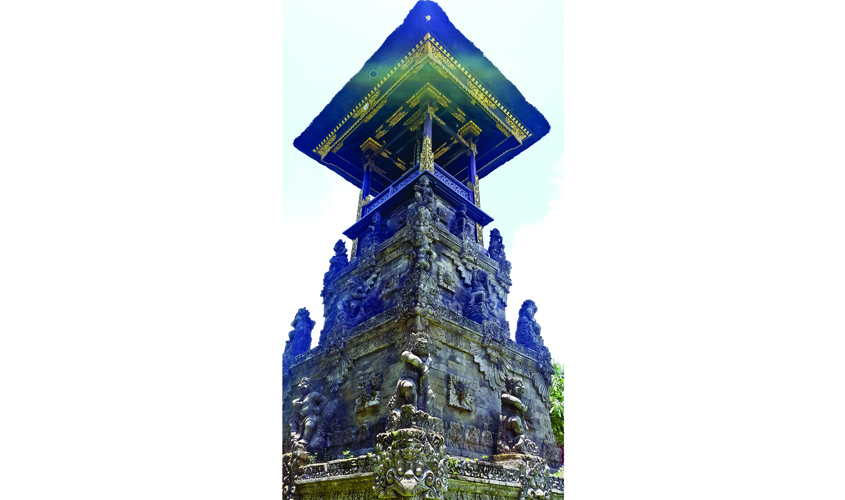

The Balinese ability to carve fluidly in stone, wood, bronze and cement, and conceptualise wonderful painted and rendered shapes and figures is evident in the profusion of the island’s statues. They are everywhere, at forks, bends, crossroads, roundabouts, in front of banks, malls and in foyers. They are all, without exception, beautifully executed, idolised, but not quite idols for worship, of Arjuna with his bow, tableaux of events from the epics, ascetics, rishis, gods, demons, asuras, apsaras, devis. And of course, Shiva, Ganesh, Garuda, Jatayu, Vishnu, Rama, Hanuman—also Chinese and Indian Buddhas, plus a profusion of happy animals and creatures, pigs, dogs, snakes, birds, frogs. Mythology and good luck symbols abound, and big trees wear chequered sarongs and boast tiny altars.

Balinese Hinduism is called Agama Hindu Dharma, originally from neighbouring Java and Sumatra, from where a number of the local people also hail. It is a blend of Shivaism, Buddhism and an exuberant animism.

It incorporates nature in its ambit, ancestor worship or Pitru Paksha, not just during the fortnight of Shradh, as in India, but daily, throughout the year, with offerings outside every home and place of work—put out fresh—flowers, food, drink, joss sticks, even cigarettes.

In Bali, people are proud of declaring they are Hindu, and 83% are, though they make up only 1.7% of the overwhelmingly Muslim population of Indonesia. There is a tolerance for others in the air, but no diffidence about the broad religious beliefs. There is beef and pork consumed on the island without any fuss.

But the Bali practice of Hinduism is very distinct from its Indian or even Nepalese versions. There is a sparseness and symbolism to Balinese ritual, instead of the din and majesty of most Indian Hindu worship. Funerals are an exception, however, with as much pageantry and noise made at the farewell, as might herald a birth or marriage here in India.

Balinese temples have carved, gated and walled-in compounds, with a number of high altars at comfortable spacing and almost always a large roofed, but not walled-in hall space for gatherings and throngs, such as they are.

Balinese homes too follow the same inside-outside villa ambience, with their temple altars, often gilded, in an inner courtyard,clusters of rooms, ranging up half levels, opening on to verandahs and gardens—in all four directions around the compound.

Entrance gates are invariably elaborate edifices, assigning status, and also designed to keep out evil spirits. They have two or three ascending steps to a short portico facing a wall, with exits left and right via a couple of steps, presumably because evil spirits cannot make turns at right angles. And almost invariably, a large statue of a seated Ganesha in the garden just behind, with fountains, flowing water and Koi fish; before the rooms sloping off behind this arrangement, again to the right and left of the courtyard.

It is like a Balinese version of imagined patrician Roman villas, not necessarily as grand, but not possible to sniff at either.

But Islamic fundamentalist tendencies are fomenting in Indonesia and Malaysia, with ISIS-like overtones. There are reports, and the long held moderation is under increasing pressure from a radicalised groundswell.

Knots of flag carrying, bandana-wearing motorcyclists speed off to rallies in Bali too, the sinister looking riot control armoured vans trundling forward in their wake.

The tattoos on the young folk, both local and foreign, are of bamboo stalks and leaves, betraying a yearning for minimalism perhaps. There are no power symbols being etched. And modish Vaping bars have begun to open up throughout the island, with cliques of people enshrouded in pleasant nicotinised smells in their effort to give up tobacco use.

The grand beach at tourist hub Kuta has surfers as always, but the nightclubs no longer have gangland pushers selling psychotropic drugs and whores.

There is a memorial to the 202 people killed in the Bali bombing of 2002 by Bin Laden inspired extremists Jemaah Islamiyah, opposite the since demolished nightclub it struck in Kuta. But like trouble in paradise designed to keep the scantily clad Western tourists away, there have been bombings since too. There were a series of car bombs in 2005, both at neighbouring Jimbaran and Kuta again, killing 20, injuring 200.

Even in 2016, Indonesian police have reportedly thwarted a new plot connected with elements in Syria.

However, the police in Bali, never fond of being intrusive or serious for too long, prefer escorting rallies of Lamborghini super cars or Harley Davidson motorcycles.

As they vroom by, you can see, some of the jackboot clad trying to keep up, senior officers themselves, grinning on BMW police issue motorbikes, hunching forward in concentration.