China relies on instruments of authoritarian influence by way of co-option and manipulation, to target media, academia and the policy community.

During China’s 40 years of reforms and opening up, developed economies such as the United States, Europe, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea etc., reaped hefty dividends from that country. These economies literally turned China into “the factory” of the world by transferring technology and investing huge sums in various sectors, while ignoring its “human rights” record and its suppression of political pluralism and freedom of speech. They hoped that their integration with an authoritarian China would result in a so-called peaceful transition, and China will eventually follow the democratic path followed by most countries as prophesied by Fukuyama.

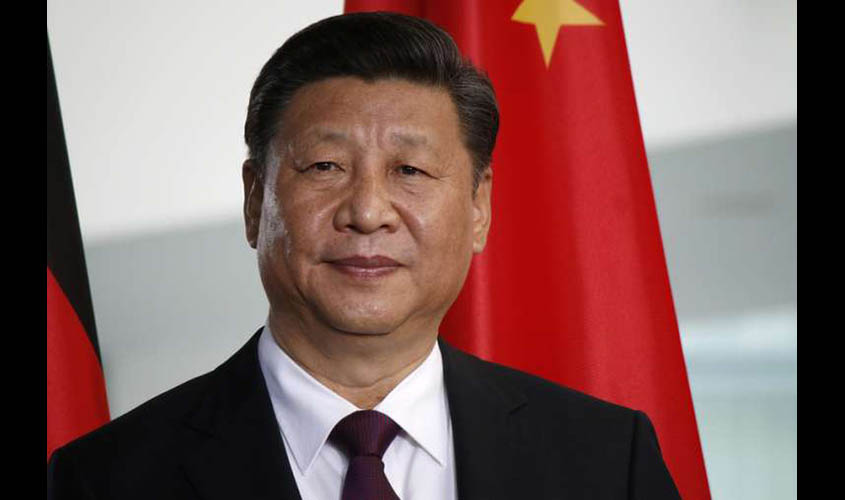

However, after four decades of hyper globalisation, China has turned the tables on the very developed economies. China, rather than treading the Soviet path of disintegration, triumphantly emerged as the second largest economy in the world, with a $13 trillion GDP, and is increasingly challenging American hegemony in its vicinity and beyond. With its ever-expanding economic muscle, China is exporting capital, technology, labour and capturing markets across continents. It is filling all possible vacuums left by US abdication from competition in the economic, strategic spheres and above all in the realm of ideas. Slowly and steadily, graduating from the ideas of building a “spiritual civilisation”, as advocated by Deng Xiaoping, to Hu Jintao’s “harmonious world” where promotion of Chinese culture is an important component, to Xi Jinping’s concepts like “cultural soft power” and “Core Socialist Values” which heavily draw from Chinese traditional value system, have been promoted inside and outside China with great enthusiasm.

The “soft power” exercised by authoritarian regimes is categorised as “sharp power” by Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig of the National Endowment for Democracy. They argue that China relying on the instruments of authoritarian influence by way of co-option and manipulation is applied to targets in media, academia, and the policy community. This “sharp power”, they say, “pierces, penetrates, or perforates the political and information environments in the targeted countries,” and enables the authoritarian regimes to cut, razor-like, into the fabric of a society, stoking and amplifying existing divisions. Joseph Nye, who coined the word “soft power” in 1990, pushes the argument even further by comparing “sharp power” with that of hard power when he says that in the context of “sharp power”, the deceptive use of information for hostile purposes is a type of hard power. However, at the same time he says that “the distinction between the two is difficult to discern”.

One of the instruments that has been often cited in this case is the establishment of over 500 Confucius Institutes and over 1,000 Confucius Classrooms all over the world by China. Secondly, as Chinese media is spreading its wings all over the world, Western media’s supremacy is being challenged increasingly. For example, Xinhua has 180 news bureaus globally; China Central Television (CCTV) has over 70 foreign bureaus, broadcasting to 171 countries and regions in six UN official languages; China has the world’s second biggest radio station after the BBC, which broadcasts in 64 languages from 32 foreign bureaus; major Chinese newspapers such as People’s Daily, China Daily etc., cover 5.5 billion people in over 200 countries. The academic collaborations, thousands of scholarships offered by China to foreign students, sending Chinese cultural troupes abroad etc., have been allegedly “taking advantage of the openness of democratic systems while denying the same to others inside China”. Making headways into joint publications such as Encyclopaedia of India and China Cultural Contacts, the goal of which according to some critics is not the scholarship but to advance political goals and portray a benign image of China. This may not be true to other projects such as the mutual translation of 25 each classical and contemporary literary works from Chinese into Hindi and Indian literary works into Chinese.

China, obviously has rubbished the concept of “sharp power” and has argued that it is essentially the reproduction of “China threat theory” and United States’ excessive concern about its own global leadership. The US and Soviet Union employed their “sharp power” throughout the Cold War. Moreover, who doesn’t use sophisticated tools for international influence? Quantum computing and artificial intelligence that have been employed to boost trade, marketisation, security, and war games by China of late have resulted in another area of supremacy. It has been reported that China’s theft of intellectual property rights has cost American companies over one trillion dollars and the US is considering punitive measures. Added to this the trade deficit of $275 billion with China owing to China not giving access to American companies such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and many others in pharmaceutical, insurance etc., sectors have made the US and western countries believe that China has increasingly raised barriers to external, political, cultural and economic influences at home, while simultaneously taking advantage of the openness and democratic systems of abroad.

During China’s 40 years of reforms and opening up, developed economies such as the United States, Europe, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and South Korea etc., reaped hefty dividends from that country. These economies literally turned China into “the factory” of the world by transferring technology and investing huge sums in various sectors, while ignoring its “human rights” record and its suppression of political pluralism and freedom of speech. They hoped that their integration with an authoritarian China would result in a so-called peaceful transition, and China will eventually follow the democratic path followed by most countries as prophesied by Fukuyama.

However, after four decades of hyper globalisation, China has turned the tables on the very developed economies. China, rather than treading the Soviet path of disintegration, triumphantly emerged as the second largest economy in the world, with a $13 trillion GDP, and is increasingly challenging American hegemony in its vicinity and beyond. With its ever-expanding economic muscle, China is exporting capital, technology, labour and capturing markets across continents. It is filling all possible vacuums left by US abdication from competition in the economic, strategic spheres and above all in the realm of ideas. Slowly and steadily, graduating from the ideas of building a “spiritual civilisation”, as advocated by Deng Xiaoping, to Hu Jintao’s “harmonious world” where promotion of Chinese culture is an important component, to Xi Jinping’s concepts like “cultural soft power” and “Core Socialist Values” which heavily draw from Chinese traditional value system, have been promoted inside and outside China with great enthusiasm.

The “soft power” exercised by authoritarian regimes is categorised as “sharp power” by Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig of the National Endowment for Democracy. They argue that China relying on the instruments of authoritarian influence by way of co-option and manipulation is applied to targets in media, academia, and the policy community. This “sharp power”, they say, “pierces, penetrates, or perforates the political and information environments in the targeted countries,” and enables the authoritarian regimes to cut, razor-like, into the fabric of a society, stoking and amplifying existing divisions. Joseph Nye, who coined the word “soft power” in 1990, pushes the argument even further by comparing “sharp power” with that of hard power when he says that in the context of “sharp power”, the deceptive use of information for hostile purposes is a type of hard power. However, at the same time he says that “the distinction between the two is difficult to discern”.

One of the instruments that has been often cited in this case is the establishment of over 500 Confucius Institutes and over 1,000 Confucius Classrooms all over the world by China. Secondly, as Chinese media is spreading its wings all over the world, Western media’s supremacy is being challenged increasingly. For example, Xinhua has 180 news bureaus globally; China Central Television (CCTV) has over 70 foreign bureaus, broadcasting to 171 countries and regions in six UN official languages; China has the world’s second biggest radio station after the BBC, which broadcasts in 64 languages from 32 foreign bureaus; major Chinese newspapers such as People’s Daily, China Daily etc., cover 5.5 billion people in over 200 countries. The academic collaborations, thousands of scholarships offered by China to foreign students, sending Chinese cultural troupes abroad etc., have been allegedly “taking advantage of the openness of democratic systems while denying the same to others inside China”. Making headways into joint publications such as Encyclopaedia of India and China Cultural Contacts, the goal of which according to some critics is not the scholarship but to advance political goals and portray a benign image of China. This may not be true to other projects such as the mutual translation of 25 each classical and contemporary literary works from Chinese into Hindi and Indian literary works into Chinese.

China, obviously has rubbished the concept of “sharp power” and has argued that it is essentially the reproduction of “China threat theory” and United States’ excessive concern about its own global leadership. The US and Soviet Union employed their “sharp power” throughout the Cold War. Moreover, who doesn’t use sophisticated tools for international influence? Quantum computing and artificial intelligence that have been employed to boost trade, marketisation, security, and war games by China of late have resulted in another area of supremacy. It has been reported that China’s theft of intellectual property rights has cost American companies over one trillion dollars and the US is considering punitive measures. Added to this the trade deficit of $275 billion with China owing to China not giving access to American companies such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and many others in pharmaceutical, insurance etc., sectors have made the US and western countries believe that China has increasingly raised barriers to external, political, cultural and economic influences at home, while simultaneously taking advantage of the openness and democratic systems of abroad.