Book exposes the dark underbelly of the Left Front that ruled West Bengal for over three decades; it proves how the killings were planned.

It’s a massacre that may remind of the Jallianwala Bagh killings. Except that this one, despite taking place in independent India, was never investigated. Not even shoddily. No one, therefore, knows how many people died in those 72 hours of savagery, organised and orchestrated by the state government of the day. Though the official figure says less than 10 people died, locals and survivors put the number as high as 10,000. And those who escaped the bullets were forced to leave for what was “more like a concentration camp or a prison”, as Amitava Ghosh writes in The Hungry Tide. Thousands more perished in the transit and at these camps.

Even more chilling has been the conspicuous silence—and muted consensus— among the intelligentsia to keep it under wraps. The sinister indifference seems even more appalling, or one should say Orwellian, when compared with the Left-liberal penchant in the country to paint a dystopian colour based on a few heinous but largely unconnected cases of violence. Maybe they kept quiet because the massacre was the handiwork of the “progressive” Left Front government in West Bengal. Or, was it because the victims belonged to the lower castes which had migrated from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) soon after Partition?

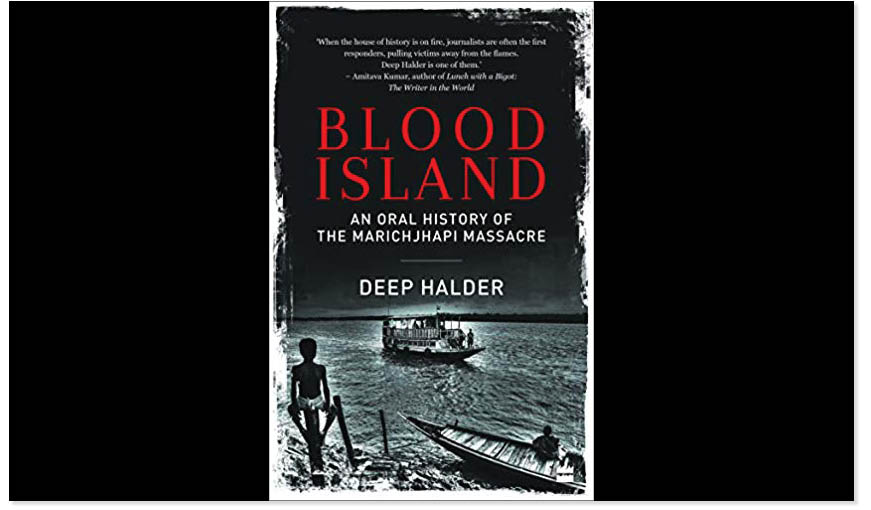

Forty years down the line comes a book that challenges the Left-liberal consensus on the killings that took place in Marichjhapi, one of the northernmost islands of the Sundarbans, in 1979. Deep Halder’s Blood Island exposes the dark underbelly of the Left Front that ruled West Bengal for over three decades; it proves how the killings were actually planned at the Writers’ Building in what was then called Calcutta. It also indicts the not-so-bhadralok nature of the Bengali elite, which looked the other way when Dalit refugees were being murdered, their homes pillaged and women raped.

It all began with refugees, mostly Namasudras, arriving on Marichjhapi in early 1978. Hailing from East Pakistan, these victims of Partition couldn’t find a roof in West Bengal and were forcibly resettled in different parts of Dandakaranya, which included parts of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. But their hopes of going back to Bengal lingered. They demanded no assistance from the government. All they sought was a small portion of land.

The communists, through the 1950s till they came to power in 1977, not only supported the refugees, but also repeatedly urged the state government to resettle them in Bengal. They denounced the attempts of the previous Congress governments to evict them from the state and promised that when they would come to power, these refugees would be resettled in the Sundarbans. No wonder, when Jyoti Basu became the chief minister

However, by the time these refugees reached Bengal, the communists had reversed their refugee policy. Several of the entrants were arrested and sent back to their respective camps. The remaining managed to slip through police cordons and reach Marichjhapi in April 1978. The uninhabited island soon turned into a bustling little town. “Over time, the population of Marichjhapi swelled to 40,000 from the initial 10,000. It had become a functional village with three lanes, a bazaar, a school, a dispensary, a library, a boat manufacturing unit, and a fisheries department even! Who could have imagined that so much was possible in so little time? Maybe all those wasted years in Dandakaranya had given us superhuman will,” Halder quotes a survivor as saying.

But the Basu government, instead of lauding their efforts, accused them of being “in unauthorised occupation of Marichjhapi which is a part of the Sundarbans government reserve forest, violating thereby the Forest Acts”; they were also charged with “disturbing the existing and potential forest wealth and also creating ecological imbalance”. Interestingly, Marichjhapi’s mangrove vegetation had been cleared in 1975 and was replaced by a government-sponsored programme of coconut and tamarisk plantation to increase state revenue.

The Basu government first took the blockade route. It employed steam launches to ensure these settlers had no access to drinking water and other essential supplies from outside markets such as Kumirmari, Mollakhali and Setjelia. When these pressure tactics failed to gain results, the government unleashed police and Muslim thugs on them. Muslim gangs were hired because the authorities believed they would be less sympathetic to these refugees from Muslim-ruled Bangladesh. Thousands died of bullet wounds, disease and starvation. Women were lined up and raped. One can get a sense of the overall casualty from the statement of a Dandakaranya Development Authority official in July 1979 that of the nearly 15,000 families that had “deserted” the camps, around 5,000 families (approximately 20,000 refugees) had failed to return.

The author must be complimented for his extensive research that helps reconstruct the buried history of the 1979 massacre. He not just digs the skeletons, quite literally, out of the communist closet, but also indicts the Bengali bhadralok of ensuring “tigers became ‘citizens’, refugees ‘tiger-food’”, a phrase used by Annu Jalais in her 2005 article. One just wished Halder had looked at the pre-Partition politics in Bengal more deeply and dispassionately. For, the seeds of Marichjhapi can be found there.