Girija Shankar Bajpai, ICS is one of the few public servants and top diplomats to live on in public memory in India for an exemplary career and his pioneering contribution in creating the Foreign Service. 5 December was his death anniversary.

New Delhi: Known during the days of the British Raj as Sir Girija Shankar Bajpai, KCSI, KBE, CIE, he was born in fairly affluent circumstances in Allahabad (Prayagraj). His father, Rai Bahadur Pandit Seetla Prasad Bajpai (knighted in 1939) was Chief Justice and Judicial Member of Council in Jaipur State.

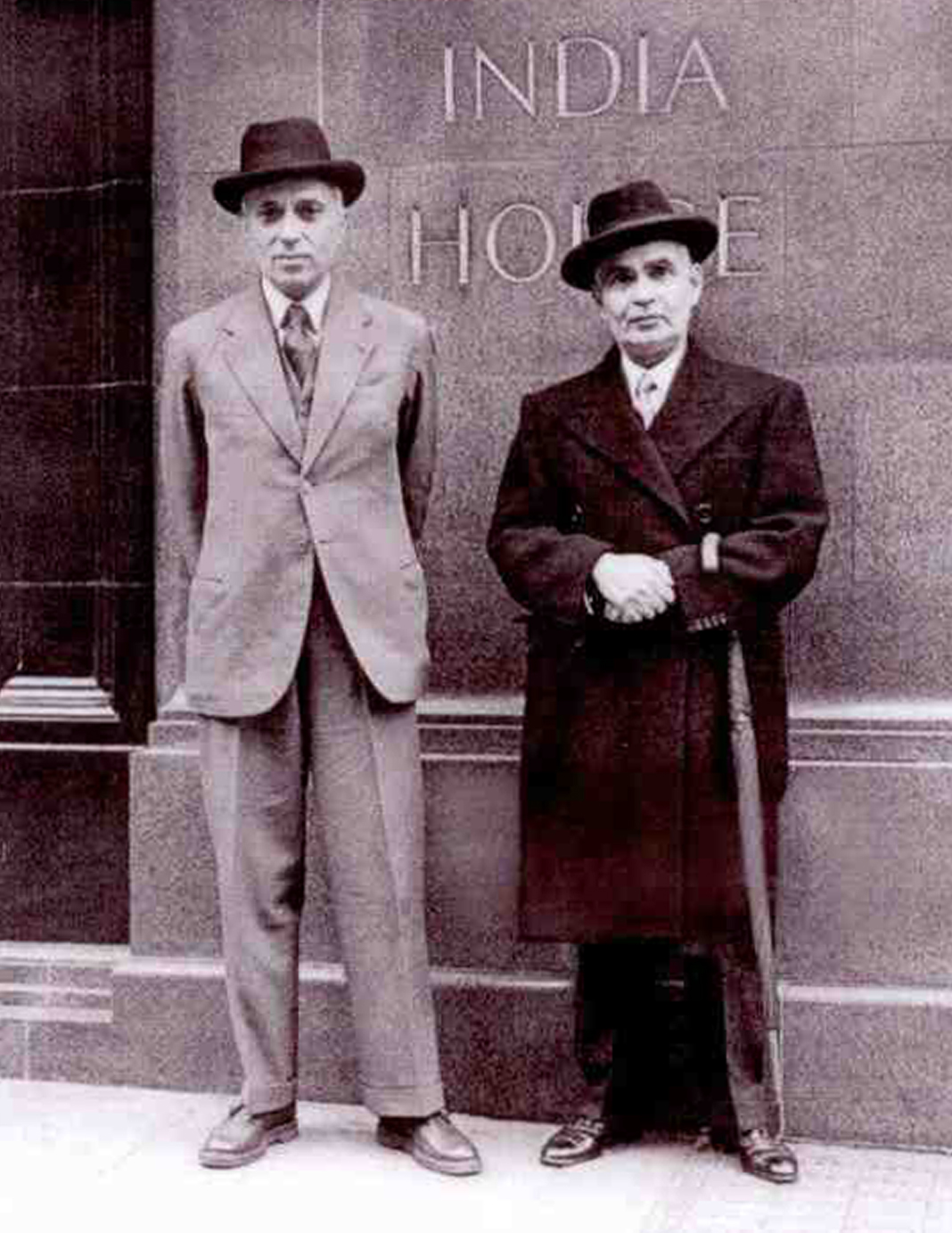

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru handpicked Bajpai (1891-1954) to begin the process of setting up an Indian Foreign Service (IFS) and to man the Ministry of External Affairs with competent personnel. His tenure as Agent General for India in the United States from 1941 to 1946 had been useful, even though this was not a diplomatic post in the conventional sense. India was not yet independent and the proposal to accord him “diplomatic status” was opposed by a diehard Viceroy, Lord Linlithgow.

If Nehru had misgivings about Bajpai’s loyalty, he did not show it. He recognised the value of Bajpai’s experience and Bajpai’s knowledge of world affairs and put them to good use.

Being the Agent General for India, Bajpai was responsible for assisting the British war propaganda. When the Interim Government decided to open diplomatic relations with the United States, Bajpai was recalled from Washington DC.

It was characteristic of Nehru not to ask him to leave government service. He was appointed Officer on Special Duty (OSD) in the Department of External Affairs and Commonwealth Relations; in July 1947, Nehru selected him for the senior most position in the Foreign Office.

The Nehru-Bajpai relationship between 1947-52 was unique. They differed often enough, such as on the China policy (where the recommendations of the Indian Ambassador, K.M. Panikkar, prevailed) and Krishna Menon’s insulting behaviour towards senior diplomats. Sometimes the disagreements came to such a pass that Bajpai would send in his resignation to the Prime Minister. As the Secretary General, he probably resigned eight or nine times. But Nehru would not let him go. He usually went along with Bajpai’s stand but when he did not, he would persuade Bajpai to stay on.

The prevailing doctrine at the time being “Panditji knows best”, very few of his close advisers questioned him. They looked upon him as a sort of oracle, an all-knowing think-tank.

Bajpai alone would express a different view. In his opinion, it was perilous for India to ignore warning signals about Chinese attitudes and intentions. He felt that China’s assertion of authority over Tibet ended any notion of a “buffer zone” and that India needed to take precautionary steps to protect her borders. The Chinese had never recognised our frontiers and the issue had to be taken up for negotiations.

Unable to convince the Prime Minister, he approached Sardar Patel who asked him to prepare a letter to Panditji—the famous letter—before sending which the Sardar added a few lines about the Communist threat. Nehru, while normally meticulous in such matters, did not reply.

The “flawed” China policy was a very costly mistake.

Initially, Bajpai’s main interest was in matters concerning the big powers and in Kashmir. Extremely hard-working and a very able draft-man for which he had few equals in the Government of India, he would take charge of the important telegrams as soon as they arrived and would be ready with answers for the Prime Minister’s approval. Nehru depended a great deal on him.

He already had, behind him, an exceptional record in the Indian Civil Service (ICS), which he joined in November 1915. He probably never worked as a district magistrate in the United Provinces. At the age of 30, he was appointed Secretary for India at the Imperial Conference of 1921 and in the same year went to Washington D.C. for a Conference on the Limitation on Armaments.

At the Imperial Conference, he observed how Jan Smuts of South Africa had become a “great figure of the Empire”; the Indian representatives only spoke when asked to comment. Bajpai noted wryly: “Silence, no doubt, is a great virtue but I think there are occasions when Speech is golden.” He wanted them to follow Smuts’ example.

Travelling abroad extensively, including for work connected with the League of Nations, he was, later, Secretary in the Department of Education, Health and Lands, ending up as a Member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council for the same Department in April, 1940.

From amongst his replies to Questions in the Central Assembly, the following anecdote caused amusement:

“The appointment of an eminent specialist had caused comment in Opposition circles and when it was known that the specialist’s wife was to have her travelling expenses paid as well, a question was put in the Assembly. Bajpai stated that ‘Mrs. X was to act as her husband’s secretary and would, therefore, receive certain expenses’.

“The Questioner: ‘Is Mrs. X’s presence a convenience or a necessity?’

“Bajpai: ‘In her capacity as Mr. X’s wife, she is a necessity; in her capacity as his secretary, she is a convenience.’

“The questioner joined in the laughter and did not pursue the matter further.”

A lover of poetry, the Persian language, art and literature, he was essentially a family man, devoted to his home, his books and his garden. Of his daughters, he is known to have said that “they are educated but not too emancipated”. His sons attended the same Oxford college, Merton, and excelled in the realm of diplomacy.

The youngest, Katyayani Shankar (K.S.) Bajpai, who passed away last August and was working on a biography of his father, recalled the Secretary General’s intervention with Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan in finalising the Nehru-Liaquat Pact of 1950 and in drafting the formula that enabled India to remain in the Commonwealth after becoming a Republic. At that time, both of these were significant achievements.

The formula evolved by Bajpai used the phrase “the Crown is the symbol of the free association of Member States and, as such, Head of the Commonwealth”; the Crown would not be sovereign of India (as of the White Dominions) but would be Head of the Commonwealth. The Manchester Guardian wrote: “Sir Girija is known for his passion for precision in words which is why he has produced a formula that will puzzle the outside world.”

According to Vincent Sheean (1899-1975), American journalist and novelist, a “technical error” on the part of officials assisting Bajpai led to India’s appeal to the United Nations on Jammu and Kashmir being considered a “dispute” rather than an “act of aggression” by Pakistan. The appeal should have been made under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter rather than Chapter 6.

Independent India could not have conducted her diplomatic relations with foreign countries through the nationals of another country. The departure of the British made it imperative to take immediate steps to recruit qualified Indians for the new Foreign Service. A handful, like Humphrey Trevelyan, stayed back briefly.

Under the British, the principal sources of recruitment to the Foreign and Political Service had been the ICS and the Indian Army. The ICS was seriously depleted by the departure of European officers after the Transfer of Power and of Muslim members to Pakistan; so were the armed services.

The normal channel of entry of young recruits into the new IFS, as to other Central Services, was to be through an open competitive examination held each year by the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC). But this method was unsuitable for recruiting a large number of candidates of different age-groups required for urgent needs. The range of selection had, therefore, to be broadened to include persons from outside government service, such as lawyers and persons with experience in trade and industry.

Bajpai proposed that, as a first step, about 30 officers, mainly from the ICS, should be seconded to the Foreign Service to provide a core of trained personnel. They would include those who had already served overseas in one capacity or another with the colonial government. Nehru approved the suggestion but urged one condition; the new recruits to the Foreign Service had to be told that they could not expect headships of diplomatic missions which were to be reserved for public personalities.

Thereupon, the Secretary General wanted to lay down his responsibilities. What career, he asked, could be offered to persons with ability if they could never become Heads of Mission? He recognised the special prerogative of the Foreign Minister to select Ambassadors but a general embargo against career diplomats would not attract capable individuals to the new Service. Nehru saw the point and did not press his objection.

In the ICS component, it is Subimal Dutt (West Bengal, 1928), Commonwealth Secretary and, later, Foreign Secretary under Nehru, who stands out as, arguably, the “best of the lot”. In 1941, he was appointed as the Government of India’s Agent in Malaya; there were also a few ICS not too far behind, like Rajeshwar Dayal (UP, 1932) and Samarenda Nath (Samar) Sen (West Bengal, 1938).

In pursuance of a suggestion of the States Secretary, V.P. Menon, a dozen or so members of erstwhile feudal families—Sarila and Alirajpur, among them—were inducted. An ICS entrant from a princely house, Lal Ram Sharan (LRS) Singh (CP&Berar, 1929), hailed from Koriya (present-day Chhattisgarh).

The Indian Foreign Service has entered the 75th year of its existence. Parmeshwar Narayan (P.N.) Haksar (1913-98), who studied at the London School of Economics (LSE), did not join through competitive examination; he flowered as a world-class intellectual. Some of the other outstanding members have not necessarily been Foreign Secretaries or favourites of a particular regime.

Along the way, much of the earlier character, analytical skills, the élan, finesse and esprit de corps have dissipated; the once-coveted IFS is no longer the goal of the student academic elite.

None of Girija Shankar Bajpai’s three successors as Secretary General matched his calibre and stature. In the final years that were marked by declining health, his services were handsomely rewarded with the governorship of undivided Bombay.

Arun Bhatnagar was formerly in the IAS.