Charu Majumdar had once said power flows from the barrel of a gun and promised to lift impoverished villagers out of a cesspool of poverty and illiteracy.

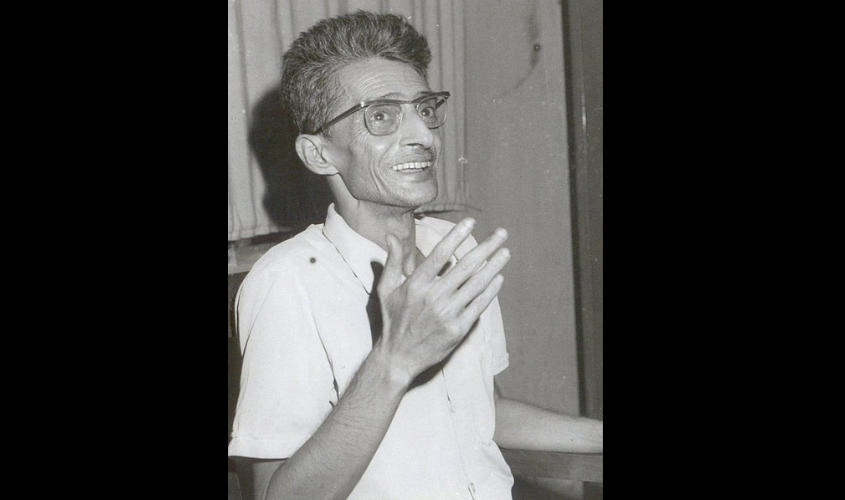

Seasoned author Ashok Kumar Mukhopadhyay once wrote a miniature book on the life and times of Naxalite leader Charu Majumdar, and now he has followed it up with a tome in Bengali. It is titled “Sottorer Sopnojoddha Charu Majumdar” that translates into “Seventies Dream Warrior Charu Majumdar”. Mukhopadhyay obviously wants Bengalis, always high on Naxalism, to read up some intricate and interesting details of Majumdar, once considered India’s most powerful dissident. He had once said power flows from the barrel of a gun and, along with his comrades, promised to lift impoverished villagers out of a cesspool of poverty and illiteracy. But eventually, the 1967 Spring Thunder did not yield results for the Naxalities. Many died, the revolution was crushed by the then PM Indira Gandhi and Majumdar died of breathing issues inside a police lockup in Calcutta (not Kolkata then).

I had expected Mukhopadhyay to start with the incident when the cops, led by Debi Roy, a police officer known for his brutalities, picked up Majumdar from a hideout. It was July 16, 1972. Majumdar was sleeping at 107A, Middle Road, Calcutta 14. Someone from the ranks of the Naxalites had spilled the beans. But Mukhopadhyay made it the last chapter, titling it the Last Hour. Mukhopadhyay mentions the name of the person who told the cops about Majumdar’s hideout. He was Dipak Biswas. Fellow comrades of Biswas, also in the police lockup, asked Biswas how he could betray the cause? Biswas told his party workers that he could not take the brutal torture. Majumdar almost died in the police lockup because of lack of medical help. The cops wanted him to sign a declaration but Majumdar refused, arguing the pages were written by the cops and the content was full of lies. Eventually, the cops gave up. Majumdar was eventually shifted to a hospital where he breathed his last.

The author says the man known as CM to his friends and followers was history. His family members rushed to Calcutta and attended the crematorium, the last rites completed by his son Abhijit Majumdar. His family wanted to take the body to Siliguri but the permission was denied. Majumdar’s death represented a major toning down of the bloody uprising that started from the north Bengal hamlet of Naxalbari and preached and practised murder as the key to revolution. The movement’s principal targets were police and rural landlords.

Mukhopadhyay highlights why the movement’s violent part was a mistake and why Naxalites, increasingly, wrongly felt they could solve the problems of the poor through force but, eventually, grew alienated from those they were trying to help. They realised through the hard way that violence was no longer their creed. It is interesting because Majumdar travelled to the hinterlands of north Bengal and urged farmers to raise their voice and demand for better lives.

Majumdar joined the Communist Party of India and began organizing peasant revolts in north Bengal in the 1940s. Inspired by Mao Zedong’s policies in China, he espoused targeted violence against the “class enemy,” that is, landlords and government.

Majumdar’s involvement in the Tebhaga movement created tremendous impact in north Bengal. The book mentions how more than The Tebhaga movement was a peasant movement in the history of Bengal and India. It was a movement of the peasants who demanded two-third share of their produce for themselves and one-third share to the landlord. Majumdar, claims the book, was in the thick of it. He could speak the local language and was able to inspire the villagers against the landlords. The clashes peaked around the month of December, 1946. The author claims with conviction that Majumdar’s involvement in the Tebhaga movement gave a great push to the demands of the impoverished farmers. A year before it gained independence, the nation watched the movement, the clashes, and the resultant death, with all seriousness. It was actually the emergence of Majumdar as a revolutionary, a leader of the oppressed class. Historians claim that it was the Tebhaga movement that pushed Majumdar to launch the Spring Thunder.

The book makes it clear that fundamental differences outnumbered points of agreement between the Naxalites and there were many disagreements, including the one on whether the big point of individual annihilation should stay or go. Or should the issue of annihilation revolve around those belonging to the upper class? And what should be the great alternative to the Mahatma Gandhi movement that was sworn to nonviolence? The author says cross-currents often messed up the Naxalite movement. And it was something that rattled Majumdar no end.

The book has loads of historical anecdotes and it would be difficult to list them all. I liked some of them, especially the ones where Mukhopadhyay narrated events that triggered the Naxalite movement. Consider this one. He lists the comments made by Majumdar on April 13, 1967: “We need to trigger the revolution, we should not delay it. Else the fruit which is ripe will rot. We are seeing silent farmers and we are wondering if they are ready to fight. No, they aren’t silent, they are all set to explode. So this is the time to hit the state, this is the time to start the revolution.” Majumdar, it is clear, wanted the farmers to stick together and he knows what would bind them is a sense of belonging, that the land is theirs and they are the rightful owners. Majumdar firmly believed India’s problems can be resolved only through revolution.

“The annihilation of class enemies does not only mean liquidating individuals, but also means liquidating the political, social and economic authority of the class enemy,” wrote Majumdar.

Egged on by Majumdar and a handful of suave Marxist ideologues, peasants around Naxalbari decided to fight back. They started sit-in protests on stretches of farmland, which infuriated powerful landlords and the state government. The police were called in to evict the farmers and many were arrested. And then, on May 24, 1967, a police inspector was killed by an arrow that came from a crowd of farmers. The police retaliated the next day, firing on another crowd, killing 11 people, including eight women and two infants. The Spring Thunder came into action.

The brutal methods of the Naxalites in killing landlords and their supporters created fear among locals. Villagers did not cooperate with the police in combing out the radicals. Many landowners fled out of fear. Soon swathes of land were becoming what Majumdar called “liberated zones”.

The book highlights another important aspect. It says although the majority of Indians were not keen to follow or support the Naxalite ideologies, there was a widespread revulsion over the way many brilliant minds were shot dead and the “excesses” committed by the Indira Gandhi government that crushed the movement. So, there was a popular demand across India for fair treatment for all those who suffered brutalities of the state.

The Naxalites Majumdar commanded are all history, there is a new breed of Naxalites or Maoists, a shadowy, revolutionary guerrilla force with tens of thousands of cadres, operating in the thickly wooded states of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand in Central India and clashing every now and then with the Indian paramilitary forces. The Naxalites call it their battle for power, land, ideology, and for the soul of India. The left-wing revolutionaries do not have a single leader, there are a number of them, and all are committed to armed revolution.

Their battlefield is far from the base of cloud-kissed hills and the tea gardens around Naxalbari that was once the incubator of India’s epic class war that left a strong imprint on today’s India.