I also remember then-Vice President Biden’s support for lifting the US visa ban on Narendra Modi after his 2014 election as Prime Minister, a step not universally popular in Democratic constituencies.

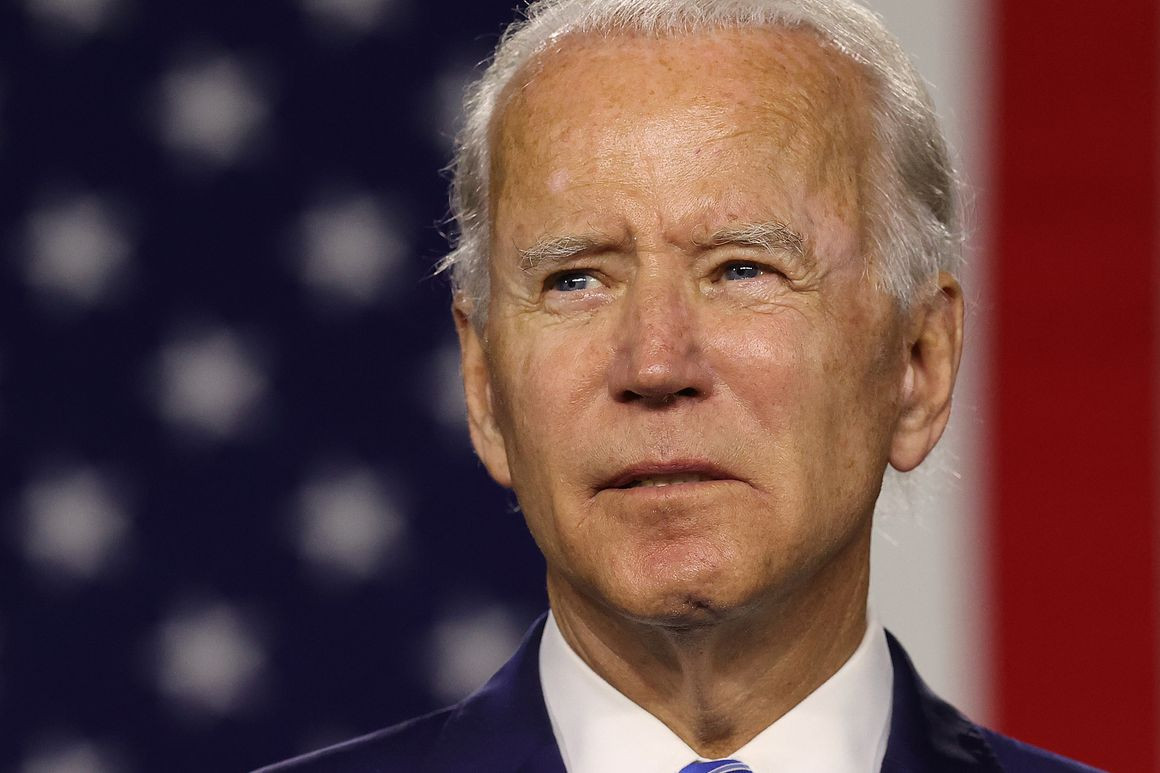

Washington, DC: Indian friends of America take heart: President-elect Joe Biden is poised to continue the upward trajectory of relations between the world’s most populous democracy and the world’s oldest one.

The record he compiled in six terms as a US Senator—during which he chaired, or was the ranking minority member of, the Foreign Relations Committee for 12 years—showcased his understanding of and affection for India, and his recognition of its potential as a strategic partner of the United States in a post-Cold War world.

His record as Vice President in the Obama administration offered other opportunities to demonstrate his sensitivity to Indian concerns and his willingness to risk political capital to defend a growing bilateral relationship.

Throughout his long career in Washington, he also cultivated important friendships in the Indian American community, a constituency whose political engagement and impact have grown with each passing election.

I clearly recall then-Senator Biden’s critical support of the US-India Civil Nuclear Agreement in his final year on Capitol Hill—a measure that he drove through his committee and that marked a turning point in ties between the two countries, but was fought by some Democrats who feared it would spark a new arms race. Years later, he spoke of the agreement as having removed “the largest single irritant between two of the world’s greatest democracies”.

I also remember then-Vice President Biden’s support for lifting the US visa ban on Narendra Modi after his 2014 election as Prime Minister—a step not universally popular in Democratic constituencies. The warmth of the reception Biden received when he visited India as Vice President in 2013 and spoke of his aspirations for bilateral trade equivalent to the trade between the United States and China attests further to his commitment to a strong bond with New Delhi.

With a circle of advisers many of whom served beside him in senior positions in the Obama administration, it is reasonable to expect the reassertion of certain Obama policies under President Biden. The designation of India as a “major defence partner” of the United States—announced in the final months of Obama’s last year in office—established a new framework for the relationship.

Similarly, the rebranding of US military forces in the region as the Indo-Pacific Command, formerly the Pacific Command, in the second year of the presidency of Donald Trump demonstrated a recognition of the centrality of India in the region’s strategic architecture, as Chinese ambitions and American interests clash. Biden can be expected to continue on that path.

It remains to be seen whether the Biden administration’s shared assessment of the strategic challenge posed by China will buffer India from US blowback over its planned purchase of S-400 surface-to-air missiles from Russia—a system that led to US congressional sanctions when Turkey was Russia’s customer last year. Should defence cooperation between the two democracies grow even closer, and the Russian system seen to pose a threat, Washington may express similar concerns.

While shared strategic interests defined the warmth and the growth of the relationship between India and the United States in the Trump years, the trade imbalance continued to be an offsetting factor, and was a particular source of irritation to the President. While the overall trade deficit grew by some 7% from 2018 to 2019, the imbalance in US manufacturing trade with India grew by more than 14% in that period.

Biden has signalled his intention to rebuild the American manufacturing base and may seek to drive down the persistent US-India trade imbalance. How successful that can be in the midst of a pandemic-induced recession is an open question.

Other issues can be expected to generate flashes of friction. A Democratic Party whose platform promised to “place values at the center of our foreign policy” is likely in the new year to see congressional—and possibly even administration—criticism of Indian actions that are perceived as discriminating against the country’s Muslim minority. The Biden presidential campaign’s Muslim-American outreach webpage derided India’s “divisive Hindu nationalist social policies, and anti-Muslim rhetoric,” while taking care to note India’s “long tradition of secularism”.

At the same time, Indians and their potential employers in America’s high-tech and medical fields may face eased work and immigration visa rules under President Biden—a relief after the Trump administration’s H-1B crackdown.

As the transition to new leadership in Washington proceeds, Indian Americans and their Jewish countrymen will continue to consult together and advocate together for the further enhancement of the mutually beneficial ties between sister democracies—as we have for a generation. We will also set as our goal a deepening of the already burgeoning trilateral partnership of India, the United States, and Israel—natural friends and allies in a hurting world.

Jason Isaacson in Chief Policy and Political Affairs Officer of the American Jewish Committee.