‘Building bridges and dialogue the only way’.

New Delhi: Something that has eluded the Hindu-Muslim amelioration mostly in the post 1947 phase, was, in fact, historically created in the form of the release of The Meeting of Minds: A Bridging Initiative, by the RSS super brain and Sarsanghchalak (chief) Dr Mohan Rao Bhagwat. Authored by Dr Khwaja Iftikhar Ahmed, one of the few nationalist pulse readers of the Muslim community, the treatise has been an unflinching votary for building bridges between the RSS and Muslims. At a time when animosity between the Muslims of India and the ruling BJP and its conceptual guardian, the RSS, seems to have been boiling in a cauldron in the aftermath of the decisions on triple talaq, Ram temple and Article 370, the book is aimed at dousing those emotions—gradually but assuredly.

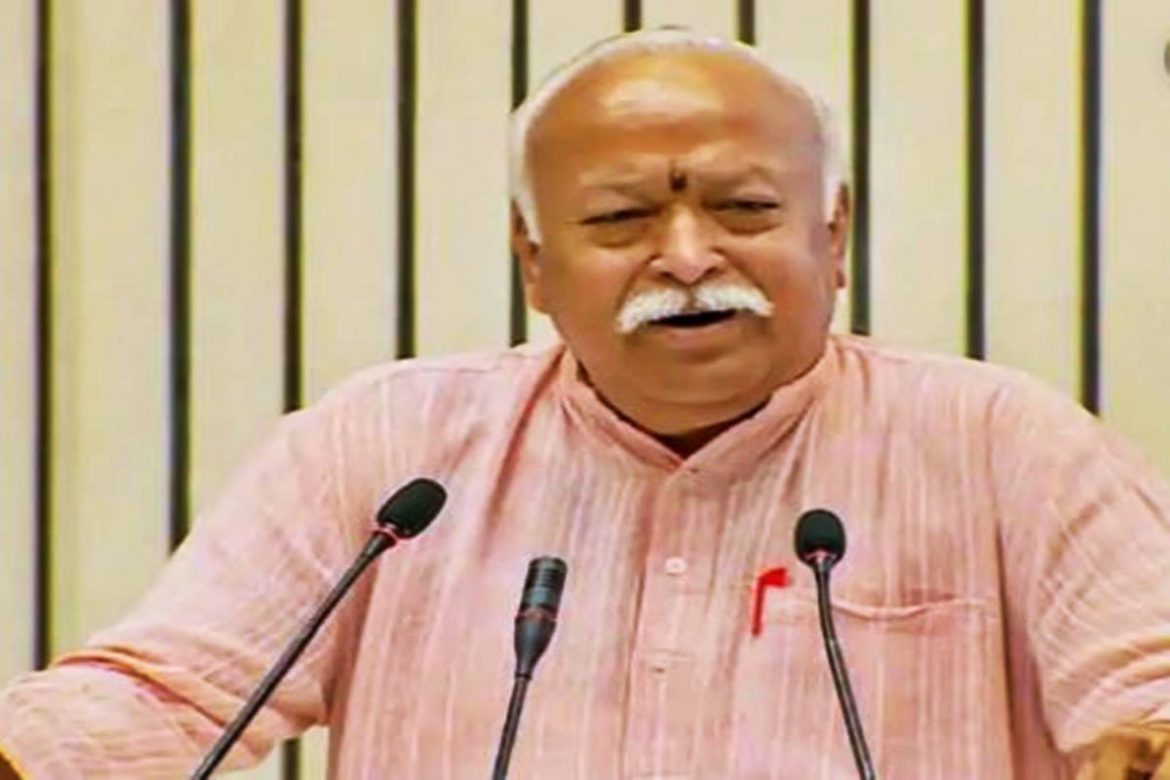

Speaking on the occasion, Bhagwat said that for the first time in the 95-year history of the RSS, it so happened that he was releasing a book, written on bridging the gaping holes between the Sangh Parivar and Indian Muslims. He made it very clear that this release was neither an attempt for image building nor was it an attempt to seek electoral gain among the Muslim community in future elections—nevertheless, an honest attempt to reach out to Muslims, whose contribution to the nation is immense.

Without mincing words, Bhagwat stated that the DNA of both Hindus and Muslims is the same and, therefore, there’s no question of Hindus and Muslims being different. They are the two sides of the same Indian coin and that there is no room for Hindu or Muslim domination. His resolve to call all Indians as Hindus was a firm cultural parameter. Besides, regarding lynching, Bhagwat made it clear that it was absolutely unacceptable. Whosoever came to India became a part and parcel of the nation irrespective of any caste or creed.

“India, by all means, is a Hindu Rashtra, all Indians are Hindus and we stand by this ideology. There is no question of any repentance on that. Sangh does not care for reactions or fallouts. What it does, accomplishes for the good of humanity,” Bhagwat made this fact crystal clear.

The book, focusing on the nation’s history between 1920 to 2020 with the mention of Bahadurshah Zafar, who glued the Hindu-Muslim diaspora with a unique togetherness against the English, mentions that bad blood began with the establishment of the Khilafat movement

Chapter-4, Secularism not alien to India, extensively covers the efforts of the Indian national movement under Mahatma Gandhi as well as the simultaneous evolution of the ideology of Hindutva running parallel with the All India Muslim League’s demand for a separate Muslim state, strengthening the rise of the RSS-BJP and Sangh Parivar. What is rued is the erosion of Hindu-Muslim amity gelling so well during Bahadurshah Zafar’s tenure, ultimately ending in the vivisection of the Indian subcontinent despite Maulana Azad shouting that the water cannot be cut in twain.

The infamous Partition leaves behind wounds, including the baggage of the responsibility of the division victimising Muslims and Urdu language—still awaiting a healing touch and kiss of life. Nevertheless, the so-called six-decade long secular polity gave way owing to its glaring loopholes of treating Muslims as fodder for their vote bank paradigm, resulting in the begging bowl of Sachar Committee, reservations and many commissions, which were no more than omissions or artificial moustaches.

The disillusionment of Muslims with the Congress and lack of faith in the RSS-BJP combine along with the so-called other secular outfits, has left the brilliant Muslim community on crossroads, and this has been detailed in the chapter Congress fails to read the writing on the wall. It aims at minimizing the widened wedge between the millions of followers of the Parivar and the 250 million Muslims of India. Unfortunately, the soft Hindutva shift by the secular politicians and the politicians, and their distancing from Muslims on public platforms makes a man in the street feel abandoned, by those whom he had trusted and blindly supported for decades. The community feels that it has been left to fend for itself. The increasing gulf between the two has created a nationwide atmosphere of enmity, something neither good for the nation nor for the two.

The author also attempts to achieve the goal of mutual harmony by picking all the issues dividing the loyalties towards each other and causing bitterness among the two sister communities on matters such as every Indian being a Hindu, religion first or the state, CAA, Vande Matram, ghar vapsi, love jihad, conversion, controversial Quranic verses, cow slaughter and vigilantism, counter claims on thousands of places of worship, Muslims and their relationship with Muslim countries, mob lynching, Ayodhya and many more. He is of the view about Ayodhya mandir-masjid imbroglio that instead of the apex court settlement, a mutual effort of resolving would have increased the faith and trust and milk of concord between the two major Indian communities.

Asked about the 26 verses in news, Khwaja Iftikhar stated that right from Abul Kalam to Abdul Kalam, the Quran runs in the veins of fifty thousand ulema (clerics) sacrificing their lives in the 1857 War of Independence; sixty one thousand names of Muslim freedom fighters are engraved on India Gate and the stories of bravery and sacrifice written by Brigadier Usman, Ashfaqullah Khan, Hawaldar Hamid and Captain Javed vouch for the patriotic zeal of Indian Muslims. The valour with which Muslim soldiers and generals in the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force are awake round-the-clock so that we are able to sleep soundly, is a testament to the Muslims’ never say die commitment. “Quran teaches us, hubb-ul-watni/ Nisf-ul-imaan, meaning absolute loyalty to the State”.

Firoz Bakht Ahmed is the Chancellor of MANUU.