The political science books for Classes XI and XII don’t mention India while talking about terrorism.

NEW DELHI: It may seem to be a case of miscommunicating the august Houses of Parliament, by the current dispensation. And the information pertains to the sensitive issue of terrorism. While the BJP-led Union government claimed in Parliament that NCERT textbooks on political science dealt with terrorism at great length, that may not exactly be the case. The political science books for Classes XI and XII don’t mention India while talking about terrorism.

On 1 December 2016, Shiv Sena leader Sanjay Raut asked the government in the Rajya Sabha whether it “proposes to introduce and include the anti-terrorism content in the school syllabus to create awareness amongst the students about terrorism”, and if so what were “the details of the measures taken/proposed to be taken by the Government in this regard”. The same question was again asked by BJP MPs Harish Chandra Meena and Sudheer Gupta in the Lok Sabha on 12 December.

Replying to the queries, the then Minister of State of Human Resource Development, Upendra Kushwaha, said that these “concerns are already reflected in the syllabi and textbooks of different stages of school education, brought out by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT)”. He then, while re-emphasising that the “NCERT Political Science Textbook for the Higher Secondary stage explains the phenomenon of terrorism to create awareness among students”, mentioned that the Political Science textbooks for Classes XI and XII “provide detailed content, including images on various dimensions of terrorism”.

There are, in total, four NCERT political science textbooks in Class XI and XII and two of them—“Political Theory” in Class XI and “Contemporary World Politics” in Class XII—talk about terrorism. But the content provided is not sufficient to create awareness among students. There is no mention of India in the entire terrorism discourse.

The Class XI Political Science book, “Political Theory”, says, “The screaming media reports on wars, terrorist attacks and riots constantly remind us that we live in turbulent times.” Reminding that “terrorists currently pose a great threat to peace through adroit and ruthless use of modern weapons and advanced technology” more generally, it says that the “demolition of the World Trade Centre (New York, USA) by Islamic militants on 11 September 2001 was a striking manifestation of this sinister reality”.

Mentioning how 19 hijackers, hailing from Arab countries, took control of four American commercial aircraft and flew them into important buildings in the US, killing nearly 3,000 persons, the Class XII book, “Contemporary World Politics”, says: “In terms of their shocking effect on Americans, they have been compared to the British burning of Washington, DC in 1814 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. However, in terms of loss of life, 9/11 was the most severe attack on US soil since the founding of the country in 1776.”

The students are then informed about the bombing of the US embassies in Nairobi, Kenya and Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, in 1998. “These bombings were attributed to Al-Qaeda, a terrorist organisation strongly influenced by extremist Islamist ideas. Within a few days of this bombing, President Clinton ordered Operation Infinite Reach, a series of cruise missile strikes on Al-Qaeda terrorist targets in Sudan and Afghanistan. The US did not bother about the UN sanction or provisions of international law in this regard. It was alleged that some of the targets were civilian facilities unconnected to terrorism,” says the Class XII Political Science book.

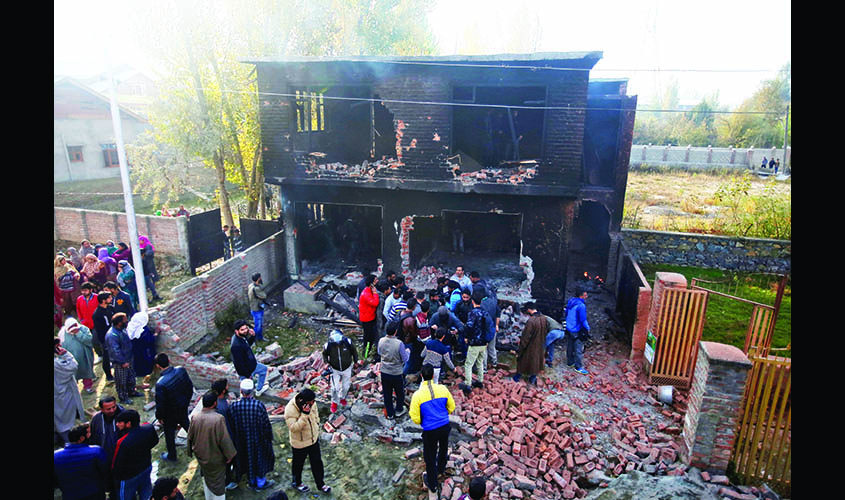

Interestingly, the same book says that the “classic cases of terrorism involve hijacking planes or planting bombs in trains, cafes, markets and other crowded places” and how since 11 September 2001, terrorism has been in the limelight, though the phenomenon itself is not new. “In the past, most of the terror attacks have occurred in the Middle East, Europe, Latin America and South Asia,” the book reminds. But the NCERT textbooks don’t talk about India. There is no mention of Kashmir, the 2002 Parliament attack, or the dastardly 2008 Mumbai attacks, Maoists, et al.

The only place where the authors passingly mention Pakistan’s role in fomenting trouble in Kashmir, Punjab and the Northeast is in the chapter “Contemporary South Asia” of the Class XII book. But the language here is non-committal. “Both the governments continue to be suspicious of each other. The Indian government has blamed the Pakistan government for using a strategy of low-key violence by helping the Kashmiri militants with arms, training, money and protection to carry out terrorist strikes against India. The Indian government also believes that Pakistan had aided the pro-Khalistani militants with arms and ammunition during the period 1985-1995. Its spy agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), is alleged to be involved in various anti-India campaigns in India’s Northeast, operating secretly through Bangladesh and Nepal. The government of Pakistan, in turn, blames the Indian government and its security agencies for fomenting trouble in the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan.”

One finds an advice on India-Pakistan ties too—this time from the Class XI book. “A just and lasting peace can be attained only by articulating and removing the latent grievances and causes of conflict through a process of dialogue.” One wonders how India can remove Pakistan’s “latent grievances” by voluntarily giving up on Kashmir? But then, as C. Christine Fair, after spending a decade in Pakistan, writes in Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War, “Pakistan’s conflict with India cannot be reduced simply to resolving the Kashmir dispute.” It’s an existential one, something which former diplomat Rajiv Dogra, too, mentioned in no uncertain terms in his book, Where Borders Bleed.

An academician, perceived to be close to the current dispensation, calls it a case of “indifference” on the part of the government. “The government isn’t bothered by what’s written in textbooks. You can see the indifference from the fact that our kids are still reading the books which were introduced in 2005, and which was supposed to be revised every five years. This government has failed to introduce its new education policy,” says he, requesting anonymity. A historian, who was earlier part of a textbook revision exercise, believes there’s another reason for the “indifference”. “They just don’t want any controversy.”

The big question remains: Why did the government miscommunicate to the august Houses of Parliament? Especially for textbooks which were brought in by the previous dispensation. Or is it that someone in the education department has misled the government itself?