If one has to go by the research findings of NASA, Sanskrit is the most suitable language to develop computer programming for their Artificial Intelligence programme.

At long last, after 74 years of our political freedom, we are coming out of the clutches and influence of the colonial mindset. One by one, different spheres of our social life are getting independence. When does a nation start progressing towards independence from freedom? To clearly understand it, we have to use the Bharatiya term, Swatantrata, for independence. If we go by its etymological meaning, the word Swatantrata is a combination of two words: one is Swa, and the other is Tantra. Swa can be defined as identity, Self or more specifically as Soul. Tantra means mechanism, method of work. Then the meaning of Swatantra is in accordance with one’s own mechanism, or according to one’s own identity, or as per one’s own soul’s direction. The main thing then is the Swa or Soul.

Though we attained freedom in 1947, we were not able to develop our own mechanism in any of the fields of our social and national life. And one such example is the field of education. It is for this reason that such deep consideration is being paid to the national policy on education. Curriculum framework, syllabi or the necessary contents can be updated as and when required. But why did we have to wait for seven decades after our freedom to formulate a national policy on education? The reason is very simple. We were unable to formulate a national policy relevant for all times. Here lies the crux of the problem. Our leaders in power were not able to recognise and respect the soul of the nation and, hence, failed miserably to formulate a comprehensive policy. As a result, generation after generation were forced to learn the content and curriculum created on the basis of a policy that has nothing to do with our Swa or the nation’s soul.

EFFECTS OF COLONIAL LEGACY

The myth that English education introduced by Babington Macaulay in Bharat is one of the best contributions made by the British was exposed by no less a person than Mahatma Gandhi. He wrote in Young India in 1920: “It is generally believed that from the time British government took in their hands the duty of educating the people of India, in accordance with the parliamentary dispatch of 1854, the country has made remarkable progress in education, insofar as the number of schools, the number of scholars, and the standard of education are concerned. It will be my business to prove that we have made no such progress in these respects—a fact which will be startling to some and a revelation to others insofar as our mass education is concerned, we have certainly made a downward spiral since India has passed to the British crown.” However, Gandhi’s disciples or those who swore by Gandhian values were never enthused by his observation and continued with the British system of education even after Bharat attained independence. Why?

Renowned Indic scholar, Koenraad Elst, who has dedicated his life to fighting the battle of decolonising Bharatiya minds, in his famous work, The Argumentative Hindu: Essays by Non-Affiliated Orientalist, writes succinctly: “It is a fact as well as a matter of wonder that sixty-five years after India gained her independence, it still makes perfect sense to discuss ‘decolonisation’. The omnipresence of the English language is the most visible factor of a permanently colonial condition, others are the total reliance on Western models in the institutions and in the human sciences.”

This continuing presence and influence of the colonial mindset has been siphoning off whatever is inherent or congenital to our culture, in a bid to delink us from our rich cultural past and civilisational ethos. During centuries of servitude, colonisers had managed to fill our mind-space with alien value systems and contempt for our culture and traditions, our real and perennial sources of inspiration. At the time of Independence, an opportunity was presented to us to place our country on the strong foundations of swadharma, but that did not happen, thanks to our myopic and intellectually slavish political masters and the left liberal intellectuals, who sought to monopolise and dominate academic and cultural institutions.

All the evil effects of colonisation can be summarised into six “I”s: Inferiority, Ignorance, Inertia, Incompetence, Ill-will and Irreverence. The first one, i.e., inferiority complex or an attitude of self-reproach is due to the dependence or irresistible fascination for the colonial education system. That’s why we find even the so-called highly educated class of our nation holding high posts and positions saying that anything related to India is inferior in quality and whatever is Western is of superior standard.

I would like to cite here an incident that happened recently. A prominent political personality with a good academic background was selected for a conferred doctorate by Oxford University. He, quite obviously, accepted the glittering honour and went there. So far so good. However, the speech made on receiving the doctorate proved to be the most disappointing moment for all who genuinely love Bharat. He was lavish in praising the country that once enslaved us. He gave all sorts of credit to that nation for our development and what not. He said: “Today with the balance and perspective offered by the passage of time and the benefit of hindsight, it is possible for an Indian PM to assert that India’s experience with Britain had its beneficial consequences too.

“Our notions of the rule of law, of a constitutional govt., of a free press, of a professional civil service, of modern universities and laboratories have all been fashioned in the crucible where an age-old civilisation met the dominant Empire of the day”.

Here is the second “I”, Ignorance. Many of our people are ignorant of the greatness of our rich heritage because we are never taught about it. The combined effect of these two “I”s creates the third dangerous epidemic, Inertia, which has crept into our very system. Though we are aware of the debilitating effect of these grave diseases, we are not ready to effectively fight against them. The incompetence rampant in all sectors is an outcome of the incompetent curriculum based on a policy delinked from our national self. When the ill-will is manifested in the form of the prevailing shameful and servile mentality, the irreverence towards all that is Indian has become the characteristic feature of intellectuals and academicians in post-independent India, which has misled an entire generation.

Those who are ridiculing everything Bharatiya as mediocre, communal, obscurantist, retrograde, are not thinking about the fact that the whole world is looking towards Bharat with full faith, with expectations and respect. They consider Bharat as their only ray of hope. They know better than the persons shamelessly continuing the colonial legacy that Bharat hasn’t yet said her last word on enlightening the whole universe. This aspect is echoing in revered Max Müller’s following words. While he was teaching the Westerners in Cambridge University in 1883 about what India can teach them, he said: “Whatever sphere of human mind you may select for your special study whether it be language or religion, mythology or philosophy laws or customs, primitive art or primitive science everywhere you have to go to India, whether you like it or not, because some of the most valuable and most instructive materials in the history of man are treasured up in India and in India only.” But, unfortunately, our then Prime Minister, who visited England after a few years, had no inhibition in claiming that it was the British who taught us everything.

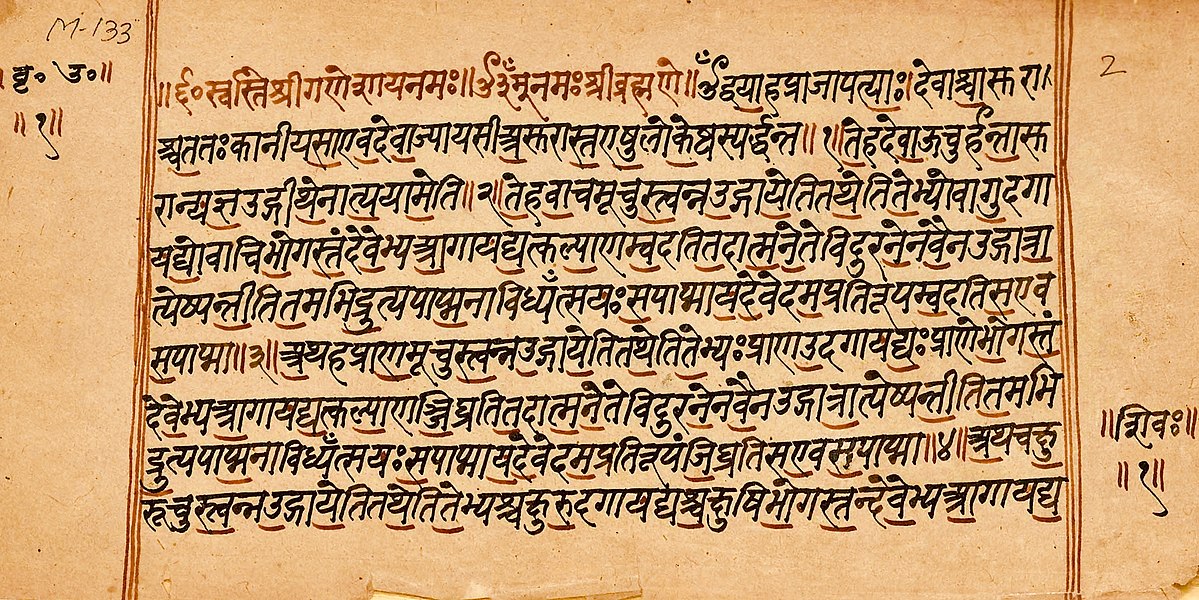

The best way to open the treasure mentioned by Max Müller is through Sanskrit and other Bharatiya languages. But how much importance have we given to our Bharatiya languages, including Sanskrit, in our language policy?

Let us, for instance, take the case of Sanskrit. All of you are aware, even before the discussion on the language policy began, a big leader, whose name I don’t want to mention, called Sanskrit a dead language, which invited a befitting response from Lakshmi Kanta Maitra, who was present in the Constituent Assembly.

Here is what Pandit Lakshmi Kanta Maitra, a member of the Constituent Assembly, representing Nabadwip constituency in West Bengal, said on 13 September 1949, in the Constituent Assembly: “If today India has got an opportunity after thousand years to shape her own destiny, I ask in all seriousness if she is going to feel ashamed to recognise the Sanskrit language—the revered grandmother of languages of the world, still alive with full vigour, full vitality? Are we going to deny here her rightful place in Free India? That is a question which I solemnly ask. I know it will be said that it is a dead language. Yes, dead to whom? Dead to you, because you have become dead to all sense of grandeur, you have become dead to all which is great and noble in your own culture and civilisation.”

What is the factual position? If one has to go by the research findings of NASA, Sanskrit is the most suitable language to develop computer programming for their Artificial Intelligence programme. That does not mean that I either approve of or am unaware of the dangers posed by Artificial Intelligence. My only intention is to stress the importance of Sanskrit as a living and scientific language. The richness and beauty of Sanskrit is that everything in it is predetermined and derivable.

Dr Ramanujan, who headed a research project on computational rendering of Panini’s grammar, says: “There is a derivational process, and so there is no ambiguity. You can explain everything structurally. There is a base meaning, a suffix meaning and a combination meaning. The base is the constant part, and the suffix is the variable part. The variables are more potent. With suffixes one can highlight, modify or attenuate.”

Unfortunately, the importance of indigenous languages was never acknowledged and our own languages by making them part of our curriculum and, hence, they continued to be criminally neglected till the comprehensive framework to guide the development of education was put in place in the form of National Education Policy 2020.

TREASURE TROVE OF CULTURE

The recently approved National Education policy is aimed at addressing this issue in a comprehensive manner. And without any ambiguity the document has drawn a phenomenal roadmap for the future of education, definitely parting from the colonial mindset. Section (22) of it, related to the promotion of Indian languages, arts and culture, starts with a clear-cut statement regarding the philosophy of language learning and culture:

“India is a treasure trove of culture, developed over thousands of years and manifested in the form of arts, works of literature, customs, traditions, linguistic expressions, artefacts, heritage sites, and more. Crores of people from around the world partake in, enjoy and benefit from this cultural wealth daily in the form of visiting India for tourism, experiencing Indian hospitality, purchasing India’s handicrafts and handmade textiles, reading the classical literature of India, practising yoga and meditation, being inspired by Indian philosophy, participating in India’s unique festivals, appreciating India’s diverse music and art, and watching Indian films, amongst many other aspects. It is this cultural and natural wealth that truly makes India, ‘Incredible India’, as per India’s tourism slogan. The preservation and promotion of India’s cultural wealth must be considered a high priority for the country, as it is truly important for the nation’s identity as well as for its economy.”

It is through the development of a strong sense and knowledge of their own cultural history, arts, languages, and traditions that children can build up a positive cultural identity and self-esteem. Great attention has been given to this particular subject in the new education policy. Let us hope that when the national curriculum framework is made, proper attention will be given to make this concept fruitful.

LANGUAGE AND CULTURE

Language and culture are integrally linked. In the true sense of the word, culture is encased in languages. Our cultural identity is being expressed in different forms and colours. That variety is the manifestation of the inherent primordial force which we call Swa or Soul of the nation. These different expressions can be seen in languages too. Here there are hundreds of languages but fundamentally they are similar.

We have to think in-depth about some major aspects related to our language studies. Ninety four per cent of our children still study in Indian language medium schools.

In spite of our bitter experience with the education system introduced by the British, independent India continued to cling on to it for over seven decades. Although, from 1948-49 to 1999, we appointed seven commissions and committees to get into the matter and give their recommendations, all such reports were consigned to cold storage and we blissfully continued with following unfounded myths.

We continued to believe that English based higher education is inevitable and the English language was the best gift of the colonialists; Bharat is fortunate to use the global language English that had contributed towards the development of Bharat and made the country a knowledge economy; English unified the people and national integration was strengthened by the use of the colonial language. Indic languages are underdeveloped and were not suitable for science and research; bureaucracy was the efficient instrument to take care of our education sector. And no attempt whatsoever was made to verify the veracity of these myths and, at the same time, its adherents boasted about their scientific temperament.

Not that there were no sane voices. But those at the helm of affairs were so enamoured of everything British, and looked down upon everything Indian with contempt, that they were never ready to heed the saner voices like that of Mahatma Gandhi, who said: “It is my considered opinion that English education in the manner it has been given has emasculated the English educated Indian, it has put a severe strain upon the Indian students’ nervous energy and has made of us imitators. The process of displacing the vernaculars has been one of the saddest chapters in the British connection… No country can become a nation by producing a race of imitators.” (Young India 27.4.1921)

We have been so obsessed with the English language, that we find it below our dignity and gauche to speak in our own language or mother tongue. In his celebrated book, Bharat Mata: Dharti Mata, the late Socialist leader, Ram Manohar Lohia, narrates an incident in which, while the Indian President inaugurated the Kalidas Jayanti, the entire proceedings were conducted in English. And Lohia, agitated over the incident, in anger exploded thus: “Shameful… We continue to be under ‘English rule’.”

And they never felt any prick of conscience to conceal facts to suit their convenience. Here are the examples: Except Indian languages, spoken by over 130 crore people, all major languages of the world are recognised in professional education, international fora and cyberspace. All developing countries, including India, who are dependent upon colonial languages, make more people poor, uneducated and undernourished than the countries developing their native language. Valorisation of official language policy that favours colonial language dis-empowers crores of people and harms the organic evolution of a link language. Bureaucratic direction in education and translation would yield no result. It is not the language used in the Supreme Court and Parliament that matters. But languages used for recruiting workforce in the organised sector should be the language of citizens for better service delivery.

Here, I would like to give just two examples:

NLCs (Native Language Countries) made the choice to empower their people by providing knowledge in their native languages and made them the vehicle of thought and research—China, Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand, Korea and Taiwan.

CLCs (Colonial Language Countries), another set of countries, were relatively better off than the former like India which continued with colonial language in higher education and administration—India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Philippines, Malaysia.

Because of our aversion to native languages and apathy, we are facing discrimination and exclusion.

For instance, Indian languages that have a glorious past have only 1,249 websites but the recently recognised Catalan language spoken by less than 5 million has 25,386 websites. Malayalam spoken by 3.5 crore people of India, who enjoy the Highest Development Index (HDI) in South Asia, is not used beyond high school. Whereas, Icelandic spoken by just 3 lakh people, enjoys the highest rate of human development in the world, and is capable of creating doctors and engineers.

As for books, if Punjab, with a population of 106.5 million people, is producing a meagre 200 books per year, Korea, with a population of just 48 million people, is bringing out 53,225 books, which is more than the total number of Punjabi books in circulation. Tamil, spoken by 6.57 crore people, has only 227 websites, whereas Italian, spoken by 6.17 crore people, has 170,121 websites. Moreover, the governments of multilingual countries, apart from maintaining websites in their native languages, also maintain websites in all major languages.

EDUCATIONAL EXCLUSION

The field of education is also facing exclusion. Hindi, the so-called national language of Bharat, spoken by 70 crore, is debarred from the classrooms of Indian Institutes of Technology and Institutes of Management, whereas in Mongolia, their language, Mongolian, spoken by less than 3 million people, is being taught in “A.B. Vajpayee Centre for Telecommunications and IT”.

In Kabul and Barcelona, their departments of medicine teach in Dari and Catalan. They are producing doctors amidst political turmoil and unrest. Can we even dream of such a proposition in Thiruvananthapuram, Chennai or Hyderabad?

Telugu is spoken by 8 crore Indians. But what is happening in our Telugu medium schools? But at the same time, schools of Scottish Gaelic language, spoken by just 60,000 people have increased 10 times in the motherland of English, the UK.

In Maharashtra, Marathi, spoken by 8 crore people, is not compulsory in educational institutions. But Welsh, spoken by 6 lakh people, is compulsory in Grades 1 to 10 in the UK. Not only that, intensive training for teachers is being planned so that all pupils can study Welsh to the level of a first language. Also, the body representing school leaders warned care must be taken not to “disadvantage” children who are not natural Welsh speakers. Moreover, intensive Welsh language training for teachers and teaching assistants is now being planned to ensure they can deliver the changes coming in from 2022. Radical changes proposed in the way Welsh is taught, mean the language will remain compulsory for all learners aged three to 16—alongside English—but no longer separated into first and second language programmes of study. Contrast this with the case of Indian languages, which cannot be used in writing research papers at Indian Institutes of Technology.

Now, let us take the diplomatic field. Here also, unfortunately, Indian languages are facing exclusion. China can write in Chinese to the Japanese government, in return, the Japanese reply in Japanese. But Bharat and Pakistan cannot conduct peace talks or conduct diplomacy in Hindi. Why don’t we communicate with Nepal in Nepali, in Bangla with Bangladesh or in Tamil with Sri Lanka?

Our employment sector, commercial sector, social field and political sphere are also facing exclusion.

The National Education Policy 2020 has taken all these aspects in all their seriousness, which is very clear from this statement. “Unfortunately, hitherto Indian languages have not received their due attention, consideration and care, with the country losing over 220 languages in the last 50 years alone. UNESCO has declared 197 Indian languages as ‘endangered’.”

To stem this slide the NEP has introduced a new language policy and it is ambitious in its scope and implementation. For example, separate academies will be created for all 22 native languages approved in the 8th schedule.

Furthermore, a plan will be formulated to encourage the use of standardised technical terminology. An emphasis will be placed on translations and works of classical importance will be translated onto other languages and be made available in libraries.

These are but a few examples of the initiatives in the new NEP policy and the thought process behind the direction that has been chosen. The Bharat of tomorrow will be grateful for the seeds we sow today.

J. Nandakumar is an RSS ideologue and All India Convenor of Prajna Pravah.