‘The New York Times did not cover the Holocaust. They published six front page articles in six years, about history’s most horrendous and heinous mechanised genocide. That’s insane.’

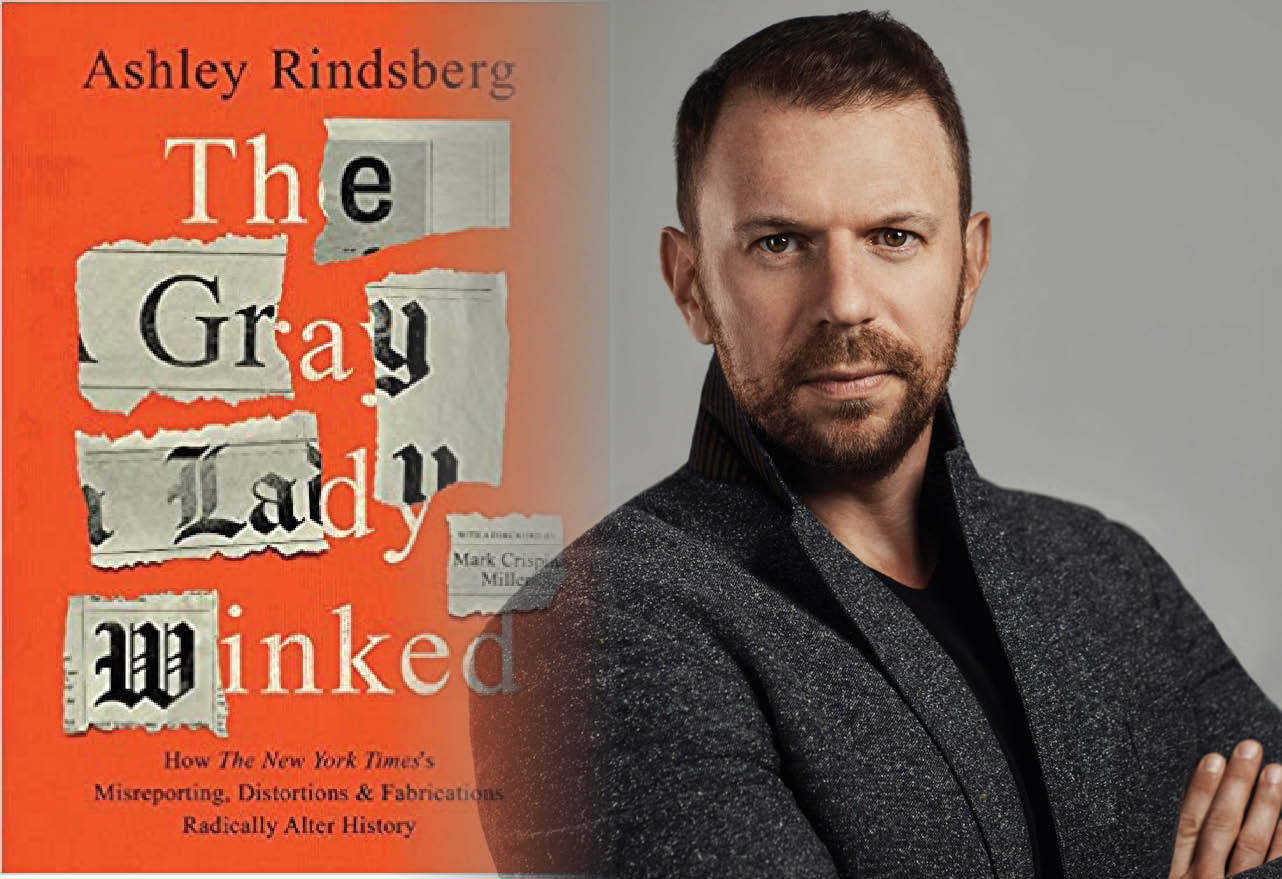

American author Ashley Rindsberg’s book, The Gray Lady Winked: How the New York Times’s Misreporting, Distortions & Fabrications Radically Alter History, is a meticulously researched, scathing scrutiny of what is published as news by arguably the world’s most influential newspaper. Rindsberg, who is currently based in Israel, spoke with The Sunday Guardian. Excerpts:

Q: What made you think of writing this book?

A: It was really sort of happenstance where I was reading this book by William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, where there was a footnote saying that the New York Times reported on the eve of World War Two that Poland or Polish forces had invaded Germany and sort of given Germany licence to retaliate, at least initially. So I started to research what happened there. And that led me to look deeper into what was going on more generally in Berlin in the 30s, with the New York Times, and their Berlin bureau. And the more I looked into it, the worse it got—praising the Berlin Olympics as the great est sporting event of all time, characterising Hitler as an unselfish patriot, reassuring readers time after time, that there was nothing to fear in Hitler, and that he was likely to just fizzle out or retire, just become irrelevant.

Again, this was like a deep pattern. So you know, you get to this combination in that particular episode, where learning that the Nazis really favoured the reporting coming out of the New York Times bureau in Berlin. And the reason was because the Times bureau chief, Guido Enderis was a Nazi sympathiser, and Nazi collaborator, he actually worked with them. That was something that was on record. And that was something that the New York Times management and ownership were made aware of. And they threatened to sue the whistleblower in response. So it just got worse and worse and worse. And once I started really getting deep into that chapter, I wanted to know more, I wanted to understand. We all know about Walter Duranty, the infamous New York Times Russia correspondent who covered up the Ukraine famine. I wanted to know what really happened. Why would a journalist deny the biggest scoop of a decade? Why would he walk away from that? It doesn’t make sense. The story about it was he just acted alone. From some whimsy he wanted to deny there was a famine in Ukraine. Why? It just snowballed like that. It’s like, you start to see that the pattern is the New York Times had a hand in these major historical episodes, it played a role in at least 10 (episodes) that are in the book, and now, another one that’s emerging, the lab leak.

Q: When I was reading the Nazi Germany chapter, I was constantly being reminded of how New York Times, in fact, not just New York Times, several other mainstream American publications are covering China. The resemblance is quite stark. Would you agree to that?

A: Yes, definitely. And I would say the comparison is relevant not only to the chapter on Nazi Germany, but also the chapter on the Soviet Union. The New York Times really seeing a market in or being part of a business consortium that saw enormous market in the industrialising Soviet Union in the 1930s, and wanted to make that potential into a business reality. And that is why when I come back to that question of, why would Walter Duranty cover up a famine? Why would he give up the scoop of a lifetime? The reason was because the New York Times needed that to be the case. Because this was a time when the Soviet Union was a 16-year-old regime, it was a violent regime, had come to power through the violent overthrow of the previous government. Their legitimacy was still in question, the US had not recognised the regime. And there came a point that major business forces in the US were pushing for that recognition to take place. So the US would formally recognise the Soviets as the legitimate government of Russia. And that would establish trade ties; that would establish this opportunity to access a market of at least, at the time, 150 million people that was the fastest industrialising nation in the world at the time.

But you could never convince the American people that it was a legitimate move to recognise these people, if they had just murdered 5 million of their own people. Stalin murdered five to seven million people in order to consolidate power in Russia in the early days, and he did it by engineering a famine in the Ukraine, in part. And the New York Times helped make that go away by just denying it. They’re the most influential newspaper out there. Walter Duranty was the most influential Russia correspondent in the US, if not the world. And by denying not only that it was happening, but denying the legitimacy of other reporters who were saying there was a famine, they were able to just create enough space for Franklin Delano Roosevelt to say, okay, let’s move ahead. Actually, Duranty personally advised FDR to proceed with recognition in an in-person meeting with FDR that was on the record. So they had this incentive to be pushing for US recognition of the Soviet Union. And it was a major stumbling block if Stalin had just murdered 5 million people as he had, so they removed it.

Q: What do you think of New York Times’s coverage of China and Xi Jinping?

A: I think it’s the same way you look at the facts, you know, you look at the reporting, let’s say in the case of the Uyghurs. If you just go into the New York Times archive, and type in Uyghur, you’re gonna see, 10 or 12 articles over the last year, and almost none of them are actual reporting on the Uyghurs themselves, on the situation, on what they’re enduring, on the mechanism of the genocide. Who are the people involved? Who are the high ranking government officials that are perpetrating this? We have reporting about the effect that it has on H&M and Zara and China. We have reporting that is very indirect, very fluffy, like what it is doing to diplomatic relations with Japan. And that’s exactly what happened during the Holocaust. The New York Times did not cover the Holocaust. They would bury tiny little stories about the murder of 600,000 Jews in Poland or Russia. They would keep it off the front page. They published six front page articles in six years, about history’s most horrendous and heinous mechanised genocide—the first mechanised genocide. That’s insane. So when we think about the Uyghurs, you are saying where is the front page coverage? Where’s the actual reporting? We are seeing the same effect with lab leak.

Why was the New York Times so invested in discrediting the lab leak from the very beginning? From February of 2020, when we barely knew there was a pandemic circulating around the world, they were already discrediting the lab leak as a conspiracy theory and they were calling it racist. For the next year and a half they pursued that one (the racist theory). Why would they prefer this? Why not explore the possibility of this other theory, which really important scientists, really credible people were saying it’s a possibility?

And again, there you look at the difference. You look at the New York Times’ business relationship with China, that they have been trying to get access to the Chinese news market for the last 10 years. And when they’ve run afoul of CCP, either policies or preferences, they’ve been blocked. And the Times is well aware that if they ever want to get that (access) back, they need to toe the party line quite literally. I think that is the calculus with the lab leak, the calculus with the Times running a huge oped a few months ago, arguing against US recognition of Taiwan as a country. How can a liberal newspaper allow such a thing to be printed in its pages—that it’s not worth recognising Taiwan? It’s the same culture. Those assumptions have become so ingrained about China, that it’s become a culture.

Q: When you’re talking about culture, so actually, this is a culture of lying, isn’t it?

A: Yeah, it’s a culture of lying. And it’s a culture/product of putting business interests or personal and ideological interests ahead of the truth. It’s really that simple when you’re saying either ideology, or business or both together. And that’s where things get really toxic, like with the 1619 project, which is both—it is very much an ideology, but it’s an ideology that’s mixed with the New York Times’ business interest, which is looking at young woke hard left audiences and catering to them by trying to reframe American history in ways that are completely illegitimate according to scholars. According to a spectrum of American scholars, these claims you’re making in the 1619 project, that is trying to reframe American history, from liberty to slavery, the claims are simply false. This 1619 project that has caused so much controversy over the last year has explicitly been made a centrepiece of their marketing strategy going forward…to reach the audiences they’re trying to reach. The important thing is, this was not about whether or not the core claims about the 1619 project were accurate or correct. They knew they were incorrect, their own fact checkers were telling them they’re incorrect. You have Leslie Harris, Professor of African American History at Northwestern University, an African American woman, who was used by the New York Times as a fact checker for some of these core claims—like the claim that the American Revolutionary War was fought to preserve slavery. Though it was a claim the New York Times was trying to make and she told them you cannot say that; it’s completely false. And they printed it anyways. And this is because the interest there was not the truth, it was not accuracy, it was not fact gathering, it was explicitly changing the narrative. And that was in service of a marketing strategy that the Times has laid out for itself. So that’s where you see this real toxic mix. And you saw it with their coverage of the Soviet Union, you saw with the coverage of the Holocaust and the non coverage of the Holocaust, as well as World War Two, it was all about staying number one, about being in the top spot.

Q: But at the same time, we see a similar coverage even in papers like say, Washington Post, and it’s a very hard left woke kind of coverage. It’s difficult to trust the news that is coming from American mainstream legacy media nowadays.

A: That’s exactly why people are not trusting them. When you look at the trust metrics within American news media, they are at all-time lows. And in the minds of the legacy media people, it’s just kind of a coincidence that trust is at an all-time low and revenue and audience numbers are also at all-time lows. I don’t think they correlate the two. But what we see is that people are just walking away. And I’m not talking about people that are coming from the right, or the hard right or even the centre right. I’m talking about people coming from the New York Times. A good friend of mine who worked at the New York Times—she was a staffer—and she revered this place as a cultural institution, she cannot open the paper today. Because what it has done is abandoned its liberal base, its liberal values of saying, okay, we’re going to at least try to approximate something or other culturally that is rooted in the notion of liberal democracy. And they’re saying, no, we’re going to aim for power, and developing this new market that’s on the hard left, that is progressive and millennial. But again, when you look at the entire history of the newspaper and you go back 100 years, which I did, in the book, you see that this is a deep-rooted pattern, because it’s the same family that’s controlled the paper since then, it’s the same dynastic interest that is legislating what goes on there. And that’s the core problem.

The core problem is that you have so much power and so much influence in the hands of so few people. And when you’re asking about the Washington Post, as an example, it’s now a cultural institution, a newspaper owned by effectively one man. And that man, Jeff Bezos has extremely deep interest in China. We’re talking about half of all the top 10,000 sellers across Amazon are Chinese. We’re talking about the most important market for their biggest division, which is Amazon Web Services, that accounts for half of their profit annually, that market will be made or broken by their ability to compete in China. And China has the ability to just say no to them.

So I think the calculus is always there, no matter who you are, unless you’re non-profit funded, but even then look at who the donors are. So it’s a huge problem. It’s that money and news don’t really mix well. And I think we’re seeing that in the US. People have been trying to make the mix for a long, long time.

Q: But if wooing the hard left crowd is not helping them financially, why still continue down that perilous path?

A: I think about that as well. When I look at CNN as another example, they’re looking at their ratings crater in the last few months since Donald Trump stepped out of the presidency; you’re looking at MSNBC’s ratings crater as well. The New York Times also probably lost some audience. So why not move more centre? Why not try to capture more of the pie? And I do think there is an element of ideology at play, for sure. I don’t think it’s only interest. I think it’s like I said before, it’s a toxic stew of both. It’s a toxic stew of saying, these are our ideological commitments, and these are our business interests. And these two things come before other things, including accuracy, including fact gathering and the truth. And sometimes in the case of ideology, they’re making the wrong choice financially. Or maybe not, you know, maybe going after a woke audience will pay financial dividends for the New York Times in 10 or 20 years. It could be the right business choice, but it’s still the wrong choice as a news organisation, because you’re not making truth, objectivity, neutrality your core values, you’re making growth a core value.

Q: Apparently you have been researching New York Times’ coverage of India. What exactly have you found?

A: The number one sales for this book are in the US, of course. And the number two by far is India. No one else competes in terms of the sales of this book, there’s so much interest. I was trying to understand what that is about. So I’ve started to look into it. And what you see is like, in the broadest strokes, the Times’ coverage of India is almost Orientalist—it’s almost as if it’s a backward place characterised by nationalism, violence, sexual assault. I read in an article somewhere, where they just flatly stated that there’s a rampant rape culture in India. And I was like, what? So, I actually started to look at the statistics to see what they meant. And you look at the statistics, and they’re a fraction of cases from what the US or Western Europe experiences. How can you make an assertion like that when the statistics are not even close to being there? So that was what I wanted to understand. I think on the broad level