Ram’s love for legal education, students and law universities remained undiminished till the end.

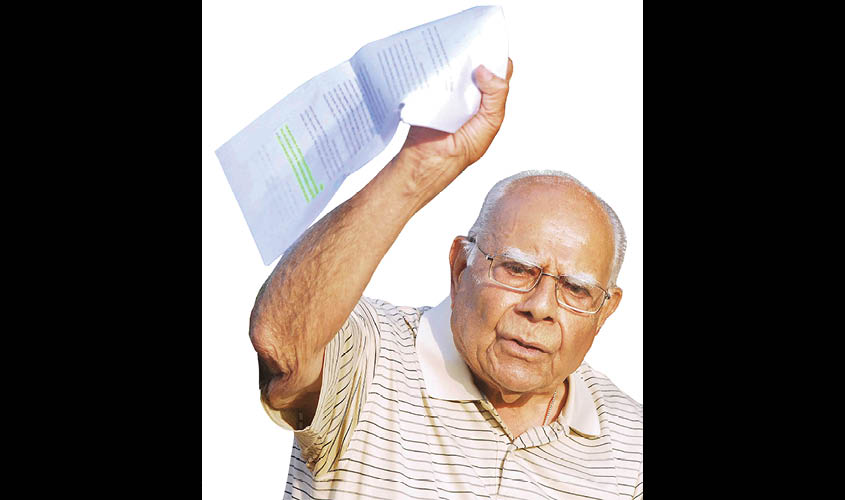

Ram Jethmalani was feisty, ebullient, fearless, outspoken to a fault and uncaring of consequences or of societal norms. He had a large heart and a restive temperament. Always a crusader, both his mind and body remained good and active almost to the end.

Ram, my wife (ghazal and Sufi singer Anita Singhvi) and I have spent many evenings of fun and laughter. His professed secret of good health—maintained till the end—was undereating. His efforts to change my teetotaller status were unsuccessful, but I made up by eating heavily while he ate a very sparse dinner. He followed the wag’s dictum with great discipline for over 75 years: breakfast like a king; lunch like a prince and dinner like a pauper. But he was ready for compensatory consumption anytime as far as liquid diet was concerned!

He was also very fond of music and attended many of my wife’s concerts. She would often end her concerts by singing Damadam Mast Kalandar, a song which holds a special place in the hearts of Sindhis. At one concert in Kamani Auditorium, Ram, well beyond his eighties, got up and started dancing to the song, roping in many more from the audience to do so as well.

Ram and I shared great chemistry, despite our age difference. Despite the fact that we agreed only 25% of the time, it never affected our mutual personal affection and regard. I always provoked him by saying that there was no party left in the country to send him to the Rajya Sabha (where he spent 30 years over five terms), since almost every major one has sent him at least once to the Upper House!

Ram’s love for legal education, students and law universities remained undiminished till the end. This started when he was made Chairman of the Bar Council of India. Till his early nineties, he would often leave everything else to deliver a lecture at Pune, Mumbai or other cities. With his passing, many legal educational institutions are today orphaned.

Ram’s fearlessness was matched only by his wit. Most know an episode when a famous anchor asked him a question that was perhaps too personal: “Did you have three wives?” Without batting an eyelid, Ram said “yes”, adding, without malice, that “even my (Ram’s) third wife is happier than your (anchor’s) first one”.

He had a large and non malicious heart. When he unleashed a vituperative attack on a former Chief Justice of India, I represented the latter. I was also on reasonably good terms with a former Third Front minister and another BJP senior minister, both of whom he hated. This never coloured our relationship. We had “matbhed” but never “manbhed”.

Ram’s feisty spirit and lifelong good health is also reflected in the fact that he played badminton regularly for six decades. I joked that the principal reason for him to find novel ways to enter the Rajya Sabha was to retain his Akbar Road residence, which had a badminton court. He played singles for decades from 5:30 am. His only concession to age was to later shift from badminton singles to doubles in his eighties. He regularly invited me to play. My standard reply was to decline, saying I would hate to lose to a person 35 years older than me and that I would not easily subject myself to such humiliation. His abiding regret was his inability to play for the last few years.

Ram frequently saw things as black and white and once he categorised something as the former, he did not hesitate to go to any lengths to oppose it, irrespective of the consequences. In the Sahara-Roy arrest case, we were both engaged in multiple petitions on the same side for the detained Mr Roy. A decision was taken to seek recusal of Justice Khehar from the bench, which was hearing the matter.

My candid and considered advice, which was later proved right, was that recusal was uncalled for, would not succeed, would divert attention from the core issue of liberty of Roy and from the illegality and lack of jurisdiction of his arrest, ending up delaying matters without getting us anything. Most of the other senior counsels, including Ram, disagreed with me.

Ram told me that he understood the spirit and core of what I was saying but would nevertheless argue recusal to the hilt because he didn’t feel that anything should be left unsaid, even though he agreed with me that the chances of relief were next to nil. He also said that even if bona fide, Justice Kehar clearly held strong views on the subject, which according to Ram he had expressed more than once and should therefore not hear the case. He argued firmly and fearlessly and put his point of view across strongly in that case, though the reaction and result was exactly as I had predicted.

I have always given Ram’s example when I repeat one of my favourite phrases—genuinely professional lawyers should neither choose their clients nor judge them. The former, unless arising from conflict of interest or logistical difficulty of appearance, would be actually unethical for a lawyer, while the latter is the job of the judge and not the lawyer.

Ram lived and practised this dictum to the hilt. He never allowed others or his own subjective predilections to decide whom he represented. If Ram had not decided to represent Indira Gandhi’s alleged assassin, Balbir Singh would never have been acquitted. In October 1984, there was probably not a single Indian who did not think that all the three accused were guilty as hell. The trial court sentenced all three to death. The High Court converted one sentence to life and upheld the death sentence to the other two. Lo and behold, only because of lawyers like Ram who appeared for the “despised, the despicable and the detested”, the apex court judgement acquitted one (Ram’s client Balbir), converted one other’s sentence to life and upheld death for only one. No one would have thought this possible on the day of Indira Gandhi’s death and lawyers choosing or judging their clients would have rendered such a result impossible. Remember, Ram fought against the media and suffered public humiliation and expulsion from his party (i.e. BJP) for this decision of his, but stood up steadfastly for his beliefs.

Ram had a very large family, and a disparate one in a sense, arising as it did from wives whom he had married at different times under the old Hindu Law. He nevertheless kept them all together under his father-figure umbrella. He suffered personal tragedies with grit and determination. When Rani fell seriously ill and suffered for a long time, Ram realised the inevitability and while accepting it stoically, fulfilled every possible duty as a father including spending long periods in the United States and ensuring that the high financial cost of specialised treatment was fully met at all times. The more recent death of his son, Janak, did break him but he never lost his optimistic outlook on life. Despite being seemingly over aggressive, he had great tenderness for his close friends and family and never hesitated in giving his all in their times of distress.

Ram was a completely self made man, from relatively humble beginnings, uprooted from his Sindhi environment, reaching Mumbai literally penniless amidst the throes and trauma of partition, and yet making it big by sheer grit, tenacity, determination and back breaking hard work. His early promise and will to succeed is reflected in the special exemption enabling him to enrol as a lawyer at age 17, the youngest ever, and passing away probably as the oldest active member of the profession. Yet another remarkable coincidence is the fact that two good friends and partners, Ram and A.K. Brohi, who started their firm in Sindh, survived all turbulences to each become Law Minister on opposite sides of the Line of Control, though at different times.

He cherished his long overseas holidays, both in the summer months and at other times of the year. He would not miss them for anything and looked forward to them. Though he would spend time with his family, he also loved to spend time abroad with friends, attend theatre, go out to restaurants and have a fun time. He had no pomposity, no arrogance and no hesitation to shake a leg with anyone and everyone.

He could be dogged and obstinate when he decided to take up an issue. He would be rigid and unmoved despite all entreaties, but if a personal or emotional or mercy plea was made to him, he would relent—not because of fear, compulsion or pressure—but because of the personal touch and an easily melting heart.

The best example of this is when he published a book in the context of his anti-corruption crusade against a now deceased former CJI. That book had many chapters castigating different people and their roles in the episode. One chapter was written about a then young minister of the BJP, and devoted entirely to that person. It was highly unflattering, forthright and would have created a stir. At the last minute before publication, on a request from one of the close friends of that minister to Mahesh Jethmalani, Ram (despite knowing that it was nothing but self-interest of the minister which had led to the plea for exclusion of the chapter), relented and excised that chapter entirely from the book (except retaining a chapter title with a blank non-existent chapter, titillating the reader). He thereby allowed the concerned minister, with whom Ram completely disagreed and against whom Ram continued to hold very strong feelings and views till the end, to save face, only on the basis of an emotional plea. In this sense, Ram always followed his heart much more than his head.

Ram’s style of law billing was unique. Very few senior counsel that I know of follow that style. Any case which he took up professionally for a fee (and many of them were pro-bono) would involve a high, even steep retainer. Thereafter he would charge normal or slightly less than normal fees per appearance but there would always be an initial and high retainer. He justified this by saying that he was uninterested in wasting time on a new case unless there was at least a semi-permanent or long term connection with that cause, that client and that case. He believed that the high initial retainer ensured that.

It was unfortunate that towards the end of his life he had a big controversy with a political party about his unpaid fee bills for appearance in the Delhi High Court in a high-profile political matter between a sitting Chief Minister and a sitting Cabinet Minister of the Central government, with Ram representing the former. I would fault Ram’s client for raising the controversy, because Ram’s fees were clear from the inception and they had no business to engage him in the first place if they were not willing to pay his fees.

Till the end, Ram remained the quintessential trial court lawyer who had made it to the apex court and not the other way round. Although he had stopped appearing in the trial courts for several decades, it was there that he loved most to go and display his flamboyance and grandstanding.

His rise to fame through the Nanavati case reflected his political and organisational skills even more than his legal ones. Few people know that the Nanavati case, apart from its legal nuances and salacious angularities, had early on also become a major battlefield between the Parsee and Sindhi communities in Mumbai, the single city with the highest concentration of both. It also started to assume the contours of a class war between the old rich and the new rich, between the elites, who would like to be seen as not sullying their hands with commerce, and the newly successful commercial and trading communities. The deceased belonged to the latter and the accused was seen as one of the former. Ultimately, the former lost the legal battle since Nanavati was convicted but he won the practical battle since he secured a Presidential pardon. Both groups thus got what each perceived to be a substantial victory. In all this, considerable skill, diplomacy and backroom negotiations were involved and all these qualities were exhibited by Ram, an upcoming member of the Sindhi community, not only as a lawyer, but in helping to design a face saver for each group.

His authorised biography sketches out several diverse and interesting facets about the man, the politician, the lawyer, the public figure, the crusader, the family man. But what it brings out most strikingly is the ever irreverent Ram, the Ram always puncturing pomposity, the Ram with a twinkle in his eye, the Ram of the ever ready repartee without fear of company or consequences, the Ram with the great glad eye for the opposite sex, Ram the raconteur, Ram the crusader and above all, Ram, the yaaron ka yaar.

We have lost an institution, spanning many sectors: law, criminal jurisprudence, politics, public life, legal education, anti corruption crusades and authorship. I will miss an elder and a friend who was warm, enveloping and gracious, a friend upon whom I could rely upon at any time. Rest in peace, Ram!

Dr Abhishek Singhvi was Ram Jethamalani’s colleague in the Rajya Sabha since 2006 up to date; Former Chairman, Parliamentary Standing Committee on Law (of which Ram was also a Member under Dr Singhvi’s Chairmanship in 2011); Senior Advocate and Ram’s colleague at the Bar for 40 years; National Spokesperson, Congress; and former Additional Solicitor General.