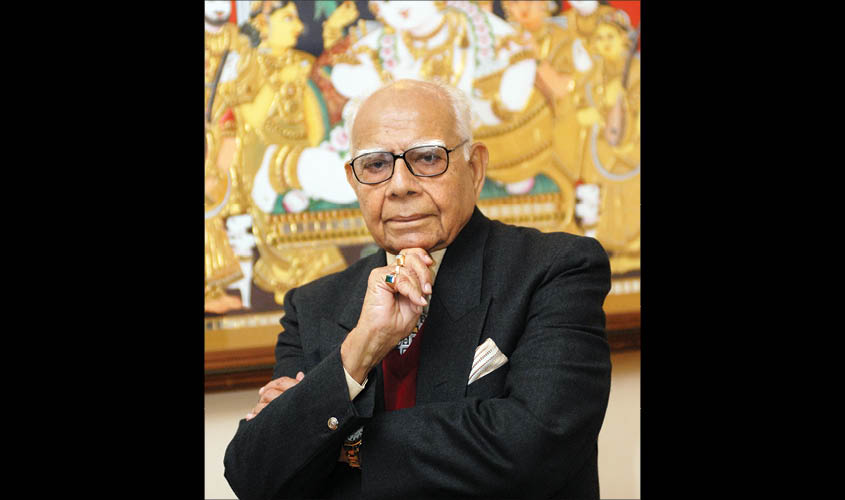

When you depart a life well lived on the cusp of a century, when you were not only a bystander but an integral part of contemporary history, you will be the subject of many tributes from friends and admirers and those seeking posthumous association with you. These tributes will focus on the highlights of your eventful life, the vicissitudes in your path you conquered and the many obstacles you converted into opportunities as well as reminiscences of times well spent together. When I was asked to pen my personal tribute, the dilemma was how to project the essence of the man with such myriad accomplishments and a personality so seemingly complex on the surface yet so simple at a basic level, beyond a biographical sketch. I knew him the better part of four decades, first as a student Youth For Janata campaigner in the elections of 1977 post-Emergency against H.R. Gokhale, the Congress candidate in Bombay’s North-West constituency and more importantly, the Law Minister in Mrs Indira Gandhi’s Cabinet and the architect of the Emergency as also in the subsequent elections of 1980 when he triumphed over Ramrao Adik. Then as a friend of his son Mahesh, who I met, freshly minted from Oxford, at the counting station in Bhavan’s College, Andheri during the 1977 elections, a friendship which culminated in a business partnership, publishing a legal magazine to which Ram regularly contributed and whose demise pained him more than us.

Over the years, he treated me with ultimate kindness, the doors of his Delhi house always open to me, a shared drink in the evening, always a part of any family occasion. The Jethmalanis gave me an emotional anchor in my most difficult times, and to them I am eternally grateful.

He introduced me to the Indian Express, helping me to realise my potential as a journalist in the days of the paper’s opposition to Rajiv Gandhi and putting the brakes on Reliance’s ambitions, especially the takeover of Larsen & Toubro. It was in the columns of the Express that his famous 10 questions riposte to Rajiv Gandhi calling him a barking dog was published. There was many a battle, in the courtrooms and outside that he fought. I was witness to one such brilliant and spell binding performance, where on an esoteric company law issue, he stepped into the breach and with the preparation of only a few hours gave a masterly dissertation for over three hours, without referring to a single chit of paper and won the matter, dispelling the notion that his mastery lay only in criminal law.

Through all these years, Ram taught many lessons by example. There was humility, not false modesty. He dealt with everyone with respect and even the junior-most in his chambers had his undivided attention. He was generous to a fault, and his generosity and position was often exploited by hangers-on, being either not a great judge of character or just not bothered beyond a point. More important, he held no grudges, even mending bridges in the last stages with Arun Jaitley and both departing with their emotional balance sheets clean in this respect.

He was ferociously courageous, even in the face of grave physical danger. His fight against the Emergency bears repetition to provide perspective. He opposed the government in the ADM Jabalpur matter, wherein the Supreme Court by a 4-1 majority held that even the Right to Life was not sacrosanct. Having earlier ferociously attached Mrs Gandhi at a local Bar Association meeting in Palghat, Kerala and seeking bail from the Bombay High Court, Jethmalani had the option of either incarceration or continuing the good fight on foreign soil. He chose the latter, earning a living by teaching in American universities, he continued to raise foreign opinion against Mrs Gandhi’s oppressive regime.

At a distance of over four decades, the sacrifices of the Emergency may appear diluted, but at that moment hopelessness pervaded. No one knew how long the Emergency was to last. It was Mrs Gandhi’s miscalculated belief in her victory and intense international pressure that led her to call elections within 18 months.

Even then there was despondency. Atalji once told me that once in jail, they did not know how long they would rot there. Once out, there was huge uncertainty at the outcome of the elections and whether they would have to make a long trek back behind bars. But his greatest act of courage was espousing the Sikh cause, especially in the aftermath of the assassination of Mrs Gandhi. He believed in the tenets of Sikhism, but he also believed in the Indian Constitution and his sworn duty as a lawyer to represent the accused. He did so at great personal and political cost defending the co-conspirators Balbir Singh and Kehar Singh, managing the acquittal of the former in the Supreme Court. He had to resign from the BJP, which he had helped found and to which he was the most ideologically aligned with his strong steak of anti-Congressism.

He went further than his lawyerly duties dictated, by arguing for dialogue with moderate Sikhs, which resulted in the accord between Sant Harchand Singh Longowal and Rajiv Gandhi. He had the temerity to label his client Simranjit Singh Mann of diminished mental capacity in a press conference in Delhi at the height of the insurgency. The cause of Punjab and Sikhs was dear to him, but greater was the integrity of the nation and he took the lead in even seeking a solution to the Kashmir issue through his own private initiative.

While Jethmalani’s legal career was at times fraught with controversy over his defence of murderers and smugglers, his politics was sometimes beyond comprehension. I have often pondered over what motivated some of his decisions like contesting for President of India or against Atal Bihari Vajpayee from Lucknow. The answer is in the essence of the man—there was never a thought contemplated, nor an act committed that was not dictated by his conscience, and his perception of what was right for the people and the country he loved. His motivation was individual liberty and civil rights and their preservation. He cared not a whit for public opinion or approbation. And he slept little but well. He had an incomparable work ethic, working 16 hours even at an advanced age, at times holding conferences on airplanes.

There is a pithy aphorism that best applied to Jethmalani—love us or hate us, but don’t ignore us. He was deeply loved by all those who benefitted from his friendship and munificence. He was hated by those who became his targets for their own misdeeds. And, because of the nature of the man and his intellectual capacity, you could afford to ignore him only at your peril.

Maneck Davar is a magazine and book publisher and is associated with NGOs working for children and the environment.