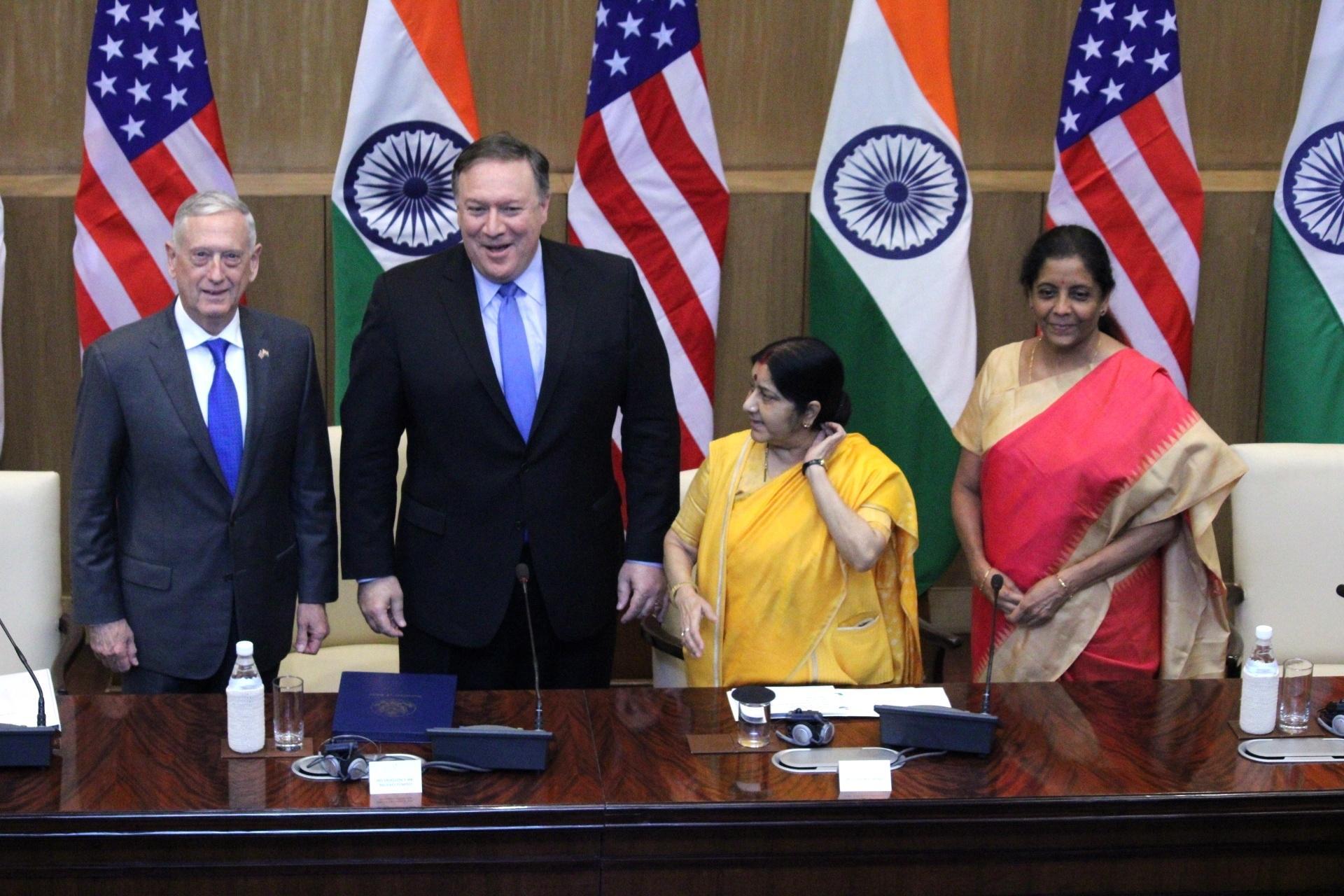

The first-ever high level 2+2 meeting between the Indian and US Defence and Foreign Ministers held last month along with the American reiteration of their offer to sell the latest model (Block 70) of the F-16 multi-role fighters and the F/A-18 fighter aircraft to India and to share technologies pertaining to the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter has presented a unique opportunity for India to not only bolster its defence capabilities, but also acquire new cutting edge western technologies while giving a boost to its self-reliance efforts.

In fact India-US defence relations have grown from strength to strength with a rapidity and scale that is as unprecedented as it was once unimaginable (during the Cold War) in the last decade-and-a-half alone, notwithstanding an earlier freeze in bilateral relations that witnessed a host of sanctions following India’s May 1998 Pokhran nuclear tests.

Beginning with the signing of the General Security Measures for Protection of Classified Military Information (GSOMOA) in 2002, followed soon after with the Next Steps in Strategic Partnership (NSSP) in January 2004, the US has of late (in 2016) termed India as a “Major Defence Partner”, which now treats New Delhi to be at par with its closest allies when it comes to transfer of sensitive military and dual-use technologies.

Earlier, on 30 May this year, the US government went to the extent of renaming the largest and oldest of its six geography-based combatant commands from USPACOM (US Pacific Command) to USINDOPACOM (US Indo-Pacific Command), thereby highlighting the significance it attaches to India in its geographical area of jurisdiction that extends from countries located on one edge of the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean.

Indeed, in less than a decade-and-a-half, the US, which once regarded India as a pariah for military sales during much of the Cold War, has most remarkably emerged as a major source of defence weapons supply. During this period India has either already bought, or contracted with, US defence equipment worth about $20 billion. This includes 22 Apache attack helicopters, 15 Chinook heavy lift helicopters, 13 C-130J Hercules transport aircraft (one has crashed), 12 P-8I Poseidon maritime reconnaissance-cum-strike aircraft (India was the first country outside of the US to be sold these aircraft), 11 C-17 Globemaster-III heavy lift transport aircraft, 145 M-777 ultra-light howitzers and a major warship (INS Jalashwa), in addition to co-development of several pathfinder projects under the Defence Trade and Technology Initiative (DTTI) signed in January 2015, that include next generation mini-Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, Roll On and Roll Off kits for C-130J Hercules transport aircraft, Mobile electric hybrid power source, Uniform Integrated Protection Ensemble Increment-2 (nuclear, biological and chemical warfare protection suits for soldiers). India’s ongoing defence modernisation and upgrading programme is expected to cost another $50 billion.

But India-US defence relations have not been about defence sales and purchases alone. There has been a rapid upgrading in defence ties that has created possibilities for India almost at par with the US’ NATO allies. Starting with former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s famous remarks to President William Jefferson (Bill) Clinton in October 2000 that it “was time to move beyond the hesitations of history”, the two sides have since then signed several path breaking bilateral agreements, starting with the NSSP, the civil nuclear agreement (October 2008) that de facto recognises India to be a nuclear weapon state without New Delhi signing the discriminatory nuclear non-proliferation treaty, established a “New Defence Framework Agreement” (2005) and the DTTI (2015), while signing three of four key foundational agreements—the GSOMOA, which permits sharing of classified information by the US government and its companies with the Indian government and defence public sector undertakings; the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement or LEMOA in August 2016 that facilitates logistical support, and the Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement or COMCASA in September 2018, whereby India can hope to get real time critical and encrypted defence technologies from the US. A final pending agreement remains the BECA or Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement.

Four tectonic geopolitical shifts in the region have necessitated India to re-examine its foreign policy options, thereby making the United States (and Israel) to be a logical choice for India’s defence requirements. The first is the highly visible economic and military rise of an increasingly assertive China that has been visible on the Line of Actual Control and in the South China Sea. The second is China’s fostering of even closer ties with Pakistan, especially with the announcement of the $48 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in April 2015. The CPEC forms part of the $1.4 trillion Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a land and sea transportation artery to link production centres in China, with markets and natural resource centres around the world that was announced in September 2013. Third, the growing defence ties between Beijing and Moscow, including the recent Russian sale of the more superior Sukhoi-35 fighters that can outpace and outmanoeuvre the Indian Sukhoi-30MKI along with also the S-300 Triumf air defence system. These two weapon systems are among a long list of other Russian defence hardware that China has since bought, only to reverse engineer and develop while being unconcerned about the sensitivities of a cash-strapped Russia. A fourth development is the warming of defence ties between Moscow and Islamabad, which has included bilateral military exercises and sale of defence equipment by Russia to Pakistan. With Russia supporting China’s BRI, it is yet to be seen whether this will mark the beginning of a Moscow-Beijing-Islamabad axis.

Russia continues to be the largest and most important source of defence supplies. Yet the fact remains that Moscow is slowly and gradually waning as a source of defence equipment. Nevertheless, some highly sensitive defence technology areas, where the Russians continue to be of help to India, is the leasing of two nuclear-powered submarines (INS Chakra-I and II), transference of supersonic cruise missile technology (BrahMos), joint development of a Fifth Generation Fighter Aircraft and sale of the S-400 Triumf air defence system. In addition to the recent geostrategic shifts, India has also been saddled with serious problems with regard to Russian military equipment. Unreliable delivery schedules, cost revisions with monotonous regularity, technology transfer hurdles and shoddy spare support have marred every major defence purchase from Russia. As a result, both operational availability and serviceability of Russian weapon platforms and systems such as, for example, the IAF’s Sukhoi-30 MKI and the Indian Navy’s MiG-29K fighters are less than 60%.

How far should India go with the US is a relevant question considering that the US has been quick to impose sanctions in any perceived violation of its (US) law and critical moments against even its allies such as Pakistan. Also, the more recent Russia-specific CAATSA or Countering American Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, threatens India’s defence purchases from Russia as this law, enacted in August 2017, is aimed to punish Russia by sanctioning persons engaged in business transactions with the Russian defence sector. The relevant section, Section 235(a), on “Export Sanction” has the potential to derail the Indo-US strategic and defence partnership, as it seeks to deny US’ licence for, and export of, items pertaining to dual use technology, defence exports and technology and nuclear technology. This is a worrisome area that India will need to negotiate with the United States. But for that India has unprecedented opportunities which would be to its advantage.