The recent inauguration of the new Parliament building marked a significant milestone in India’s 76-year history of Independence. For the first time, Indians have constructed a Parliament that is entirely their own, free from the influence of a colonial legacy. While the older Sansad Bhawan held great historical importance in Indian politics, the new Parliament building seeks to emphasize the spirit of democracy from an Indian perspective. In doing so, it reaches back to the rich heritage of democracy that India possesses through references to Indian history through maps and murals. The symbolic placing of the Sengol signifies this continuity with change and tradition with modernity.

As is known, India’s democratic legacy extends far beyond the very origin of democracy itself. The fact is that democracy in India was not only established earlier but was also more organized and inclusive than its counterparts in the West. For instance, in Athenian democracy, two-thirds of adults, which included foreigners, enslaved people, and even women, could not participate in the legislative processes. And yet, the narrative is forwarded as if the West and democracy are coterminous. For long, India has either willingly or tacitly consented to such narratives while being unaware, ignorant, and often ashamed of its own history.

Nonetheless, this is no longer India’s approach. As a country and civilization, India is undergoing a profound transformation where it is becoming more confident and vocal about its actions and achievements. An excellent example of this came during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s address at the 76th session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), where he proudly proclaimed, “I am representing a country which has the distinction of being named as the ‘Mother of Democracy.’ We have had a great tradition of democracy for thousands of years.” These powerful words shed light on the deep-rooted democratic traditions that have shaped India’s history. In particular, the reference to “Mother of Democracy” highlights the vibrant democratic heritage that predates many modern Western democracies. This stands on strong historical facts of the Uttaramerur inscription, which came into existence 800 years before the Magna Carta.

From ancient times to today, India has been shaped by democratic principles and institutions that have laid the foundation for its progress and inclusivity. The earliest sources of India’s democratic principles and traditions were the Indus Valley Civilization and the Sangam period. Later, the examples of Uttaramerur and the AnubhavaMandapa stand as testaments to India’s rich democratic tradition, emphasizing the importance of inclusive governance, participatory decision-making, and the power of dialogue. Looking into these historical examples and their implications, one uncovers the intricate tapestry of India’s democratic tradition that continues to guide the nation’s path forward.

India’s democratic heritage can be traced back to its ancient roots, as reflected in the mentions of “gana” and “sangha” in texts like the Mahabharata, Panini’s Astadhyayi, and Buddhist scriptures. These references provide insights into the existence of republics and confederacies, illustrating the decentralized nature of governance and the active participation of the people. The Vedic era, in particular, sheds light on the democratic essence through two significant assemblies: the samiti and the sabha. These terms signify the presence of decentralized forms of governance and collaborative associations. Such historical evidence highlights the early democratic principles embedded within Indian society.

Among these references, the Mahabharata is the first textual source to mention a republican form of government, employing the terms “gana” and “sangha”. This indicates that the concept of self-governing bodies and collective decision-making was already prevalent. One noteworthy example of early democracy found in the Mahabharata is the samiti. It served as an experiment in direct democracy. This system continues to exist in some parts of the world today. The samiti operated as a platform for the active participation of citizens in decision-making processes. It played a crucial role in electing and re-electing kings, demonstrating the democratic principle of popular choice and accountability. Attendance at the samiti was mandatory for the king (Rājan), emphasizing the importance of their interaction with the people.

In addition to the samiti, the sabha was another notable assembly during the Vedic era. It was closely associated with the samiti and was often considered its refined counterpart. The sabha, a “body of men shining together,” functioned as a house of elders. It was significant, as even deities and respected sages attended its sessions. The sabha acted as a parliamentary body for conducting debates and discussions on matters of public interest, reflecting the democratic ethos of open dialogue and deliberation. The position of sabhapati, the chairman of the sabha, was held in high esteem. The modern-day Upper House of Parliament (Rajya Sabha) is widely considered a successor to sabha. Consequently, the samiti represents the modern-day Lok Sabha or the Lower House of Parliament.

Basically, these ancient democratic institutions demonstrate the early recognition of participatory governance in India. They showcase the active involvement of citizens in decision-making processes, the significance of collective wisdom, and the value placed on eloquence and debating skills. Such assemblies reveal the deep-rooted democratic traditions that have shaped India’s political history. The samiti, resembling a legislature, convened to discuss state matters and elect or re-elect kings. It emphasised the importance of a true king attending the assembly, signifying accountability to the people. The sabha, a body of elders, conducted public business through debate and discussion, reflecting the values of free expression and collective decision-making. In other words, these early democratic institutions paved the way for inclusive governance and highlighted the significance of open dialogue and participation.

Within the vast tapestry of India’s democratic heritage, the Anubhava Mandapa and the Uttaramerur inscriptions stand out as significant examples. The Anubhava Mandapa was founded by the visionary social reformer Basavanna in Karnataka during the 12th century and, thus, holds great significance in India’s history. This institution can be seen as an early version of a parliament, where mystics, saints, and philosophers assembled to discuss various topics encompassing society, economy, culture, and spirituality. Basavanna’s foresight led to establishing this public forum a century before the famous Magna Carta emerged in England. Situated in Basavakalyan, Karnataka’s Bidar district, the Anubhava Mandapa played a pivotal role in fostering an egalitarian renaissance, thereby serving as the genesis of parliamentary democracy in India. Scholars, poets, and philosophers congregated at this place to exchange knowledge and insights, cultivating an atmosphere of inclusivity and progressive thinking. This tradition exemplifies the deeply ingrained democratic values within India’s cultural and intellectual heritage. By embracing the lessons from these ancient democratic institutions, India can strengthen its dedication to inclusivity, ensuring that every voice is acknowledged and represented.

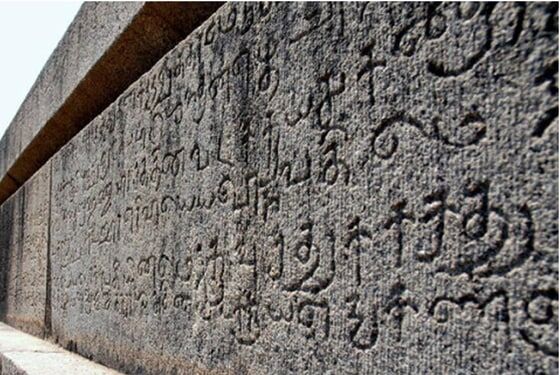

Another is the case of Uttaramerur, a historical village in Tamil Nadu that provides a remarkable example of a well-organized democratic structure that thrived in ancient India. Established in 750 CE, it boasted of a vibrant democratic system with temples, wards, dependent hamlets, tanks, and roads. Meticulous planning and inclusivity were the cornerstones of Uttaramerur’s electoral system, ensuring that only eligible individuals who met specific qualifications could contest elections.

The village consisted of 30 wards, and during elections, the entire community, including infants, would gather at the village assembly

Inscriptions found in Uttaramerur provide valuable insights into this efficient system of governance. More than 200 inscriptions discovered in the village shed light on its self-governance abilities and the sophistication of its local population. The system discouraged corruption and wrongdoing, as elected members who engaged in such practices faced disqualification. Furthermore, committee members were ineligible for re-election for the subsequent three terms. The inscriptions found in Uttaramerur shed light on its self-governance abilities, revealing a system that discouraged corruption and provided checks and balances. As such, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s references to the Anubhava Mandapa and the Uttaramerur inscriptions underscore India’s democratic heritage that as he correctly pointed out, predates the Magna Carta. These examples demonstrate the deeply embedded nature of democratic traditions within India’s social fabric long before their formal establishment in the modern era.

For such profound reasons, India’s democratic legacy holds invaluable lessons that can shape the nation’s future. Upholding the principles of inclusivity, accountability, and participatory governance is vital to safeguard the nation’s essence. Moving ahead, India must firmly cherish its democratic values and nurture the seeds of democracy sown by its ancestors. By drawing inspiration from its illustrious past, India can serve as a guiding light for democratic ideals, leading the way in promoting equality, justice, and prosperity for all its citizens. The preservation and celebration of India’s democratic heritage will pave the path for a brighter future for generations to come.

While reflecting on India’s rich democratic legacy, one must also remember the words of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee: “Governments will come and go, political parties will emerge and fade away. However, India should remain; its democracy should remain immortal.” Upholding the democratic principles derived from ancient experiences is essential to protect the nation’s soul.

In conclusion, the Anubhava Mandapa and the Uttaramerur inscriptions are remarkable testaments to India’s thriving democratic traditions since ancient times. They illuminate the presence of well-structured institutions and inclusive electoral systems that predate Western notions of modern democracy. As India progresses, it must draw inspiration from its illustrious past and deeply cherish its democratic values, ensuring they continue to shape the nation for generations to come. It is a paradigm shift that we are not only stating, accepting and building an alternative narrative, but also challenging the hegemonic Western narrative of superiority and civilizing mission that were constructed on a false consciousness.

Prof Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit is Vice Chancellor, JNU.