A major marker of the new cold war was the Covid pandemic. Two years of the pandemic brought the worst features of China to the fore.

The post-cold war international order was underpinned by three elements. The unipolar status of the United States, increased globalisation and the impending rise of China. China’s credible challenge to US unipolarity in the last decade triggered de-globalisation. An imbalance in the existing world order became visible. In the recent past, four new elements burst onto this scenario. They were the onset of the pandemic, the Ukraine war, revivalist ambition of Russia to regain great power status and the rise of India. These four have completely upset the balance in the global order, which is now on the verge of collapse. The global order is more pronounced by a pervasive disorder underpinned by deglobalisation. It portends to be long drawn.

The cold war was dominated by two opposing ideological positions with the iron curtain firmly separating them. With the fall of the iron curtain, ideological barriers disappeared and geoeconomics took centre stage. The globalisation of the post-cold war era established connectivity and dependencies between most nations. However, in the current period of pervasive disorder, de-globalisation has gained pace, self-interests of nations are more predominant and great power ambitions are more pronounced. We have entered into an era of the new cold war.

The new cold war has no ideological moorings. It is all about China aspiring for superpower status, Russia attempting revival of superpower status and the US retaining its unipolar superpower status. The economic moorings of the new cold war are strange. The linkages and dependencies of globalisation remain between competitive forces. As a result, alignments of opportunity and convenience have come to the fore. Most importantly, the new cold war is dotted by numerous wars of trade, technology, nuclear revivalism and military wars. Aggressive attitudes have given rise to new powers and contributed to failure of states. The new cold war is being fought simultaneously at multiple layers through ideology, technology, economy, diplomacy and military means. Many a times these are at cross purposes with each other. In this context it is important to disaggregate the kaleidoscope to understand what are the constituent wars in this new cold war.

The first shot of this cold war was fired by President Trump when he declared a Trade War in 2018 against China. He imposed punitive tariffs on Chinese imports in order to reduce trade deficits. This was followed by restrictions on China’s access to high-tech U.S. products and foreign investments, citing security concerns and IPR theft. Allegations were also levelled against unfair commercial practices by China. It started the process of deglobalisation and it continues to linger.

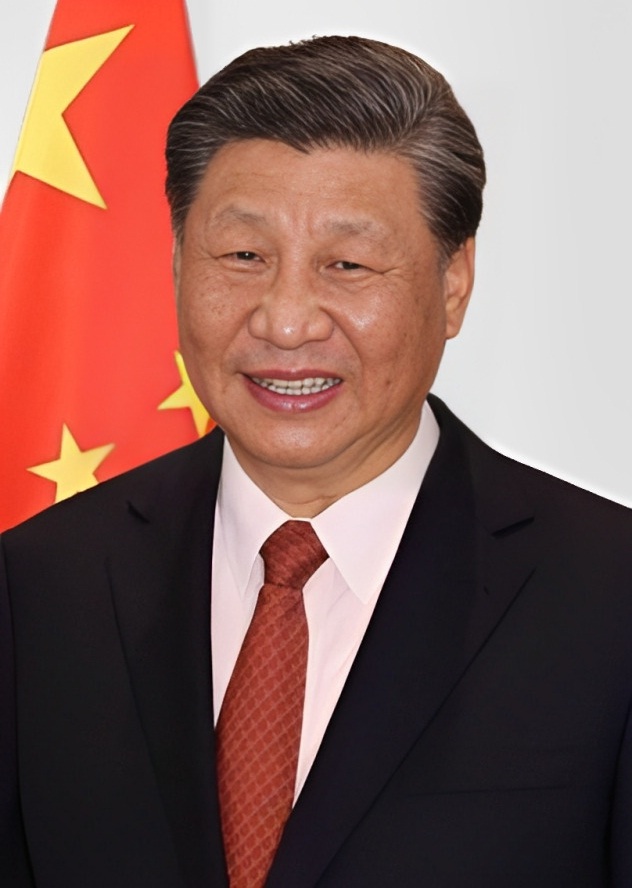

The next major marker of the new cold war was the Covid pandemic. Two years of the pandemic brought forth the worst features of China to the fore. Its refusal to share data to pinpoint the origins of Covid, its military assertiveness and wolf warrior diplomacy was accompanied by a supremacist attitude that its form of autocratic government was the best. Democracies were portrayed as weak and ineffective in curbing the virus. Mask and vaccine diplomacy followed, along with Zero Covid policies. It led to severe disruption of supply chains and hardship to many countries. These countries have taken it upon themselves to strengthen the supply chains by reshoring/friend-shoring/decoupling from China. This period also saw China make a determined effort to get rich before it gets old and establish a Sino-centric world order at the expense of the US. For many obvious reasons this was not acceptable to the US and the West. Hence, one sees many narratives come out from all sides, decrying each other. However, the net effect has been that there has been a visible decline in China’s CNP, which it intends to make good through efforts at self-sufficiency by leveraging technology, diplomacy and its military. A tug of war is visible with major multinational corporations decoupling from China and relocating elsewhere. China is doing its best to reverse this drain. This will continue for long and will hasten deglobalisation.

The second major event of this period has been the ongoing Ukraine War which has lasted more than a year now. Also, it does not seem to be ending soon. It has pitted most of the nations in the Western alliance in a proxy war with Russia through Ukraine. The proxy war is being fought militarily between Ukraine and Russia. The West and Russia are locked in an energy, diplomatic and economic struggle which is more known as a hybrid war. This war has polarised the globe and fractured existing connectivity and dependencies on food, energy and other primary resources. Resultantly, there are mini wars in these domains which are going on. The Ukraine War has also highlighted limitations, pitfalls and dangers of Chinese ambitions in annexing Taiwan in a quick military swoop to thereafter establish a Sino-centric order. More importantly, it has taught Taiwan the value of resolute resilience which can stymie Chinese aggression.

The most significant development in the Indo-Pacific emerged from Chinese military assertion when Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan. When China demonstrated its military might and threatened blockade of Taiwan, other nations in the region felt threatened. They started arming themselves and making arrangements with each other to handle China in a joint manner. Further Chinese assertion has resulted in solidifying the Quad and gave life to AUKUS. The Chinese military build-up and its indication of increasing reliance on its military might has brought the US back into the area as it deploys its military power in four bases in Philippines. All in all, the territorial contestation in the Western Indo-Pacific is turning into a major flashpoint of serious concern.

Chinese ambition to be the foremost military power kickstarted an internal process of increasing and upgrading its nuclear arsenal in the past three years. This is being put in effect alongside its quest to militarise space as also develop hypersonic weapon systems. In addition, Russia threatened the use of nuclear arms in the Ukraine War to keep NATO out of it. Both these events have triggered a process wherein most nuclear nations are reassessing their options to respond by their own upgradations. Further non-nuclear nations like Japan and South Korea are now contemplating going nuclear. In addition to all this there is burgeoning trade between Russia and China in nuclear material. It is well possible that we are already in the midst of a nuclear cold war.

The next major contestation is in the field of semiconductors where the chip war is underway. China started the process by IPR theft of semiconductor technology through its civil military fusion process. Reflexively, the US has put in place the CHIPS Act to deny technologies critical to development of wafer-thin semiconductors which are essential in quantum computing, AI and space technologies. The US’ CHIPS Act will deny to China three important aspects of chip technology—the design (from the US), the lithography (from Denmark) and production engineering (from Taiwan). In the meanwhile, China is determined to be self-sufficient in this technology. This war has just begun.

A major fallout in this period is that as deglobalisation started, nations began consolidating, forming fresh partnerships and seeking safe shores to protect their citizens. Resultantly, there is a wave of nationalism with nations seeking self-sufficiency in essentials like food, water and energy. This has been accentuated with supply chain disruption due to the pandemic and realignment/redistribution of global energy and resource networks due to the Ukraine war. If things were not gloomy enough, the threat of climate change is hanging over most of us. This was evident in extreme events in Europe, China and Pakistan. As a result, there is a global upheaval and turmoil in food markets. Fundamental food security has assumed centre stage as never before. Water as a basic resource for food and energy production has come to the fore and water wars are on the table especially in the Asian landmass, with water deficient China as the upper riparian in most major rivers emanating from the Tibetan Plateau.

Amidst all these goings on, middle powers like India, Indonesia and Japan are on the rise. China is being forced to react to this rise. Simultaneously, smaller nations in Asia and Africa which were debt ridden are collapsing. The cases of Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Gambia and Zambia are prominent. Some of these states are becoming battleground states for big power contestation. Amongst the big powers, China and Russia are making efforts to oppose the consolidation of the US and the West. Hence, it can be seen that there is a flux at all levels of nations whether they be big or small. There is widespread international turmoil which is destabilising societies to say the least. If this is not the new cold war, what is it?

Overall, the new cold war is being played out at multiple levels in multiple facets. It is a war in which each country is for itself. Partnerships, alliances, alignments and agreements are more opportunistic and will be temporary in nature. One has to be conscious of the fact that India is growing and developing in this fractured environment. It must never forget to look after itself first. To a large extent, the experience of being self-dependent during the non-aligned period will help us adopt a neutral path in this cold war to ensure the safety, security and welfare of 1.4 billion people of India.

A common question will be—how long will this last? The last one lasted three decades. This one is more complex and will be conditioned by the unknown factor of climate change and environmental degradation. Hence by most common assessment and metrics, it should last well into the latter half of this century. We are in for troublesome times. Brace for it.

Lt Gen P.R. Shankar PVSM, AVSM, VSM (Retired) is a retired Director General of Artillery. The General Officer is now a Professor in the Aerospace Department of Indian Institute of Technology, Madras. His articles are available at www.gunnersshot.com