True to the tradition of Indian yogis, Xu roamed around India searching for knowledge and fulfilment.

Imagine you being sent by a government and there is a regime change soon after your departure, which is followed by a bitter class struggle, cleansing of the bourgeoisie and confiscation of properties of landlords! Imagine if you have to spend decades away from your home and return only in your old age!

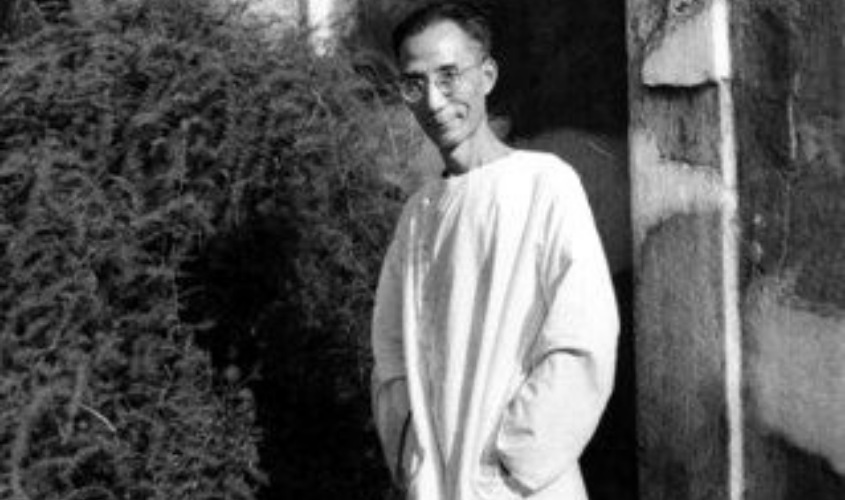

Xu Fancheng’s (1909-2000) destiny was somewhat similar. He was sent by the Nationalist Government of China to Visva-Bharati University at the end of the War of Resistance Against Japan in 1945 to teach Chinese. Four years later, Chiang Kai-shek’s government fell and so dried the source of funding to Xu. Whether on his own volition or for the fear of reprisal, Xu stayed back in India and returned to China in 1978 at the age of 70. A scholar par excellence, who majored in philosophy from Heidelberg University, Germany, attained highest standards in Sanskrit and Indology, was remembered only after his return to China and acknowledged only recently. The class struggle had ended with the demise of Mao Zedong and his Cultural Revolution (1966-76) and China was at the cusp of unfolding unprecedented reforms and open door policy.

True to the tradition of Indian yogis, Xu roamed around India in search of knowledge and fulfilment, which he found in Banaras to start with, where he mastered Sanskrit and in Aurobindo Ashram, Pondicherry where he stayed for the next 27 years and gave full play to his expertise in Indian, Chinese and Western civilizations. It was in Banaras that he translated works like Bhagavad Gita and Kalidasa’s Meghduta; and in Aurobindo Ashram the Upanishads from Sanskrit to Chinese, the first Chinese to perform such a feat. His numerous works on the Indian, Chinese and Western civilisations are collected in 16 volumes of the Collected Works of Xu Fancheng, published by Shanghai Joint Publishing Company in 2006. In the post Mao era, as China embarked on the international stage to spread its soft power, people like Xu Fancheng became relevant.

It was perhaps in the course of his teaching in Visva-Bharati that he authored books like Quintessence of Philological Studies and Confucianism Explained in English for his foreign audience. Xu was an out and out Confucianist. He had a deep understanding of the development of Confucianism throughout the dynastic history of China—the Axial Age, state philosophy of Han and its revival during the Song by the “Five Masters”. These according to Xu are Zhou Dunyi, the author of Book of Zhou Zitong; two of Zhou Dunyi’s students—Chen Hao (1032-1085) and Chen Yi (1033-1107) brothers; Zhang Zai (1020-1077); and Zhu Xi (1130-1200).

No wonder, Xu also considered Zhou Dunyi as his teacher and chose to translate Book of Zhou Zitong written by Zhou Dunyi, in English. He compared Zhou Dunyi with Sri Aurobindo, his spiritual guru, for he believed that Aurobindo was the true inheritor of the mainstream Indian culture and studies of Vedas, Upanishads, and Bhagavad Gita. Xu believed that the Chinese nation could survive and preserve its culture because of its character that has an indelible imprint of Confucianism. He believed India too will rise like a phoenix from the ashes and have a great future because of its strong civilizational character. In his words, “While evaluating the true value of a nation, one should not confine one’s vision only to the present, a person should not only look back to its long history, but also to its infinite future. …A nation might be neglected temporarily, but the glory of its past and its contribution to the mankind cannot be written off. Acknowledging the past, signifies the hope for a great future. After the baptism of fire, the sight of phoenix rising from its ashes is much magnificent than before.”

It was perhaps for his understanding of the Indian and Chinese civilizations that he tried to find connecting links between the philosophies of the two. According to him, Bhagavad Gita is compatible with Confucianism, conforms to Buddhism and leads to Daoism. In the preface of the translated edition of Bhagavad Gita, after expounding these facets, Xu Fancheng lamented that post Xuanzang (602-664) and Yijing (635-713), China gradually regressed as far as understanding of India was concerned; China hardly knew that besides Buddhism, this nation had its own fundamental laws and principles. In the same vein, India also failed to understand that besides Buddhism, China too had its own fundamental laws and principles. He recognised the fact that China’s research on India had fallen far behind in modern times, therefore, he resolved to change this situation through his own efforts. In his words, “If, from now on, we continue to collect and translate Indian classics, we will positively have a better reservoir of scriptures than the Buddhist or Taoist canon.” True to the efforts of Xu Fancheng, today China has rendered almost the entire repository of mainstream India’s classic, modern and contemporary works. Beside Xu, the credit must also go to other gentle academic giants of Indology in China like Jin Kemu, Ji Xianlin, Huang Baosheng, Liu Anwu, Jin Dinghan, Wang Shuying, Wang Bangwei, Yu Longyu and the younger experts led by Jiang Jingkui.

Xu Fancheng has compared Indian culture to a tropical forest, which he said abounds in invaluable woods, vines and weeds, wherever the eyes meet. However, in the midst of mithyā-drsti it becomes difficult to find the right path. Therefore, he says setting his hands to the Bhagavad Gita was like finding a treasure. Besides translating Bhagavad Gita and Upanishads, Xu also translated Aurobindo’s works such as Essays on the Gita, Foundation of Yoga, Essay on Yoga 1: Yoga, a Holy Profession, Essay on Yoga 2: Integral Yoga, Essay on Yoga 3: Sacred Love Yoga, Essay on Yoga 4: Yoga of Self-perfection, Collected Books on Yoga. The Theory of Sacred Life, a masterpiece running into more than 800,000 words. Most of the Chinese works published by Xu Fancheng in the 1960s were from Ko Tam Sing’s printing press in Hong Kong. On the last page of the published book was noted “Chinese Section of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, South India” or just “The Chinese Section.” Starting from 1970, Sri Aurobindo Society Singapore took over the printing and composition of Mr. Xu’s works in Chinese.

In the year 2000, when Mr Xu departed from this world, the newsletter of Sri Aurobindo Society, Singapore published a special issue (Vol 14, September 2000) to commemorate Xu Fancheng. This issue has now become the main source of information on Xu’s 27 years in Aurobindo ashram. The Society also planned and organised an exhibition on his paintings in his memory. In 2002, when Patel Nandlal, editor-in-chief of the newsletter of Sri Aurobindo Society, Singapore visited China, he donated more than 5,000 copies of Xu’s works published in Singapore to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

As far as Indian studies in China are concerned, Xu Fancheng, Ji Xianlin and Jin Kemu are the three pillars of the study of Sanskrit in modern China. As regards the academic evaluation of Xu Fancheng, Ji Xianlin and Jin Kemu, Lu Yang posits that “Mr Xu is a very special person in the galaxy of modern intellectuals. Many of his accomplishments in humanities are beyond the reach of his peers. One of his strengths was that his mastery in Chinese and Western classics far exceeded that of Mr Ji Xianlin, and was more systematic than Mr Jin Kemu.” During the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, Xu’s name was entered in the records of Pondicherry Exhibition Hall along with Sri Aurobindo and St Mother, mirroring his indispensable role in Sino-Indian cultural exchange. The introduction read: “Though very few Chinese know, the city of Pondicherry in fact has played a prominent role in cultural exchanges between India and China in modern times. This is due to the influence of the Chinese scholar, who lived in Pondicherry for 27 years. His name was Xu Fancheng, also called the “Modern Xuanzang”.

This article has been compiled on the basis of the author’s forthcoming translation of Yu Longyu and Liu Chaohua’s work titled “China and India: Dialogue of Civilizations”.

B.R. Deepak is Professor at the Center of Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University.