Job’s obsession with the Indian sadhu culture, with Buddhism, is well known. But how he incorporated this spiritual practice in revolutionising technology is something that is not quite known. When you look back at Job’s career, it’s easy to spot the influence of Zen. For 1,300 years, Zen has instilled ideas of courage, resoluteness, and austerity in its practitioners. Jobs incorporated this idea into Apple argot in his own way — an idea of simplicity.

Zen is everywhere in the company’s design. Take, for instance, the evolution of Apple’s signature mouse: it became the industrial design equivalent of the enso, or hand-drawn circle, the most fundamental form of Zen visual art. But Zen didn’t just inform the aesthetic that Jobs had an intense commitment to. It shaped the way he understood his customers. He once famously said in one of his interviews that his task wasn’t to give people what they said they wanted; it was to give them what they didn’t know they needed. When he died, the New York Times ran a stirring quote about what he did for society: “You touched an ugly world of technology and made it beautiful.”

From never knowing what the basic job of a computer was or how it ought to be designed, Jobs went on to be the maker of Apple products that are till today considered different and infinitely more “cool”. The Macintosh introduced the world to the computer mouse; the iPod became famous for its click wheel, and the iPhone for its “user interface” — a sophisticated touch-screen that responds to the flick of a finger. Jobs is also the man behind the astonishing success of the computer animation firm Pixar, makers of Toy Story, Finding Nemo, which expanded viewership of animated films worldwide.

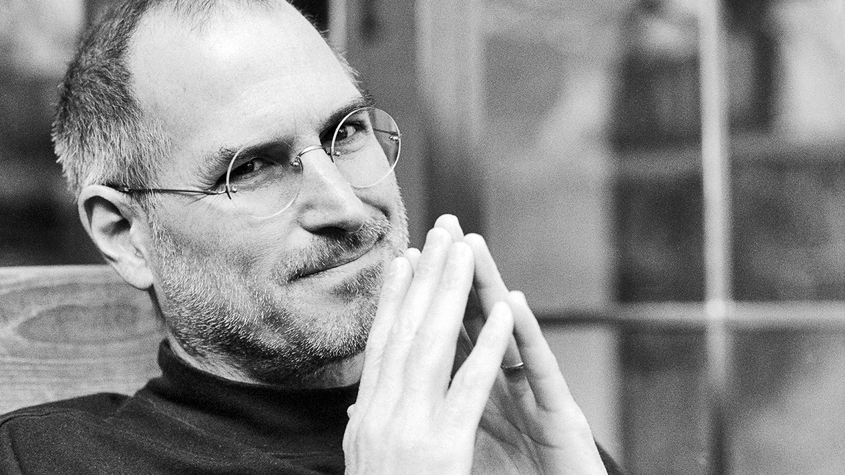

Haters will be haters but for Apple-hungry consumers, Steve Jobs will always be the visionary genius whose powerful leadership can never be forgotten. On a tribute page, a web user by the name of Sidharth had echoed similar feelings, “Steve changed the world, not once or twice, but several times,” he said. “His genius raised the bar for customer-centricity and gave us something to look forward to. He created magic and almost single-handedly kept the wow factor alive.”

It was five years ago, on 5 October, that the Apple giant left for his heavenly abode on. Co-founder and CEO of Apple, he left after a long struggle with pancreatic cancer. His death, at 56, came a few months after he stepped down from the company after handing it over to Tim Cook, a long-time friend and collaborator.

Zen is everywhere in the company’s design. Take, for instance, the evolution of Apple’s signature mouse: it became the industrial design equivalent of the enso, or hand-drawn circle, the most fundamental form of Zen visual art.

Last year, Donald Trump who lists the top of troll charts today had mocked the company saying, “ Steve Jobs is spinning in his grave — Apple has lost both vision and momentum — must move fast to get both magic back!” This and other post-Jobs social media criticism, even among greats like Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates has been based on Apple’s turnover that had fallen bit by bit from its peak of $775 billon that Jobs had made it reach. Therefore, this gives us more reasons to take a look back at Steve’s legacy, which is of course not without flaws.

He had launched some category-defining products and not-so-category-defining ones like the Apple Lisa, Macintosh TV, Apple III and Apple Newton. Even some of the greatest products came with embarrassing flaws, like the iPhone 4’s signal drops, which had been a matter of dismay for many a customer and which being later on mitigated as the company began offering free smartphone covers.

Jobs was born on 24 February, 1955 to a Syrian Arab father and an American mother, who had travelled to San Francisco to put him up for adoption. Soon afterwards a blue-collar California couple, Paul and Clara Jobs, claimed him and named him Steven Paul.

After completing high school in Cupertino, northern California, Steve went north to study at Reed College in Portland, Oregon, but dropped out after a term. Returning to California, he took a job at Atari, the video games manufacturer, in order to save money for a “spiritual quest” to India. It was here that he was converted to Zen Buddhism and vegetarianism.

On his return to America, Steve resumed his work with Atari and was given the task of creating a more compact circuit board for the game Breakout. He had little interest in the intricacies of circuit board design and persuaded his 16-year old friend, Steve Wozniak, to do the job for him. In 1976, Wozniak showed his friend a computer he had designed for his own use. Steve was impressed and suggested marketing it. They had no capital, but Steve had a brilliant idea. By persuading a local store to order 50 of the computers, then asking an electrical store for 30 days credit on the parts to build them, they set up business without a single investor. They called it Apple Computers and launched their first product, the Apple 1. A year later the more sophisticated Apple 2 hit the jackpot, and by 1980, when the company went public, the pair were multimillionaires.

The rags-to-riches story of Steve Jobs story has been likened by Apple fanatics all over the world to the life of Christ. And for the less blasphemously-inclined, it proved that the American Dream is alive.