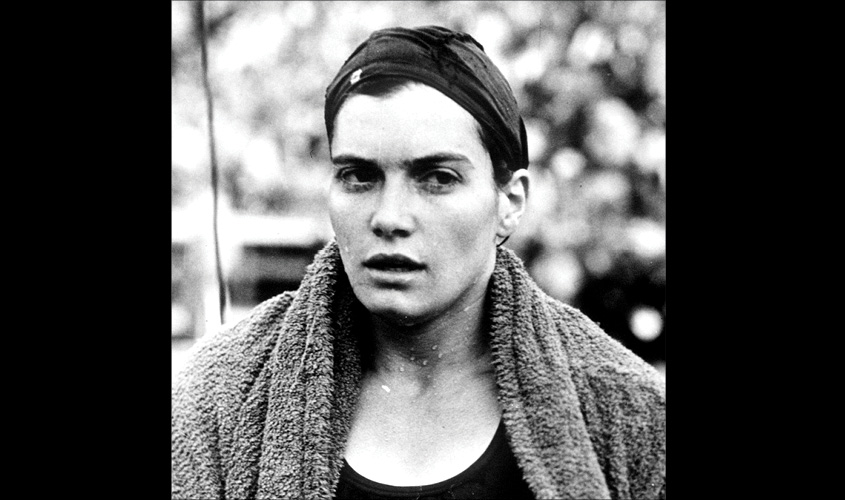

Eva Szekely, an Olympic champion swimmer and an athletic hero in her home country of Hungary, narrowly escaped being murdered by fascists before she could achieve greatness.

Already a promising swimmer as a girl, Szekely (pronounced “SAY-kay”) was forced off her swim team in Budapest in 1941 because she was Jewish. Fascist forces within Hungary made things progressively worse for Jews there, well before the Nazis occupied the country in 1944.

An official in the Arrow Cross Party, a Hungarian fascist organization that controlled the country with Nazi support, at one point ordered Szekely to march to the Danube River, where fascists killed about 20,000 Hungarian Jews that winter. Her father told her to lie down and act too ill to move, then he tried a different tactic.

“For some heavenly influence my father said, ‘Don’t take her, she is the swimming champion of Hungary and one day you will be happy you saved her life!’” Szekely told the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation Institute in videotaped testimony in Hungarian subtitled in English.

Szekely recalled staring into the official’s eyes, one gray, one brown, before he let her live. She survived and fulfilled her father’s prophecy, winning a gold medal in the 200-meter breast stroke at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, and a silver in the same event at the Olympics in Australia four years later.

Szekely died on Feb. 29 at her home in Budapest. She was 92.

Her death was confirmed by Gergely Csurka, the media manager for the Hungarian Swimming Association, in an email.

Amazingly, Szekely found a way to train during the war. According to her entry in the Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, she endured part of the war in a crowded, Swiss-run safe house in Budapest, where she ran up and down five flights of stairs 100 times every morning.

She entered international competition soon after the war ended in 1945, and won dozens of swimming titles beginning in 1946. She first competed in the Olympics at the 1948 Games in London, where she came in fourth in the 200-meter breast stroke.

Two years later Szekely had a chilling encounter after winning an international swim meet in Hungary. She was told that in addition to her gold medal she would receive a special prize from an important officer of the communist political police.

She said that the officer handed her the trophy as she stood atop a dais, they made eye contact, “and it was that Arrow Cross man, with his different color eyes! I thought I would fall off the platform!”

Early in Szekely’s competitive days she met Dezso Gyarmati, an extraordinary water polo player who helped Hungary win five Olympic medals, including gold at the 1952, 1956 and 1964 Games. They married in 1950.

At the 1952 Olympics, Szekely set an Olympic record in the 200-meter breast stroke with a time of 2:51.7 and was part of a dominant Hungarian women’s swim team, which won gold in four out of five events. She and Gyarmati had a daughter, Andrea Gyarmati, in 1954. Before they left for the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne an anti-communist revolt, quickly quelled by the Kremlin, roiled Hungary and prevented athletes from training in the last weeks before the games.

Szekely and Gyarmati, an outspoken

Many Hungarian athletes opted to remain in Australia or defect to other countries once they learned that the Soviets had prevailed in Hungary, but Szekely and Gyarmati returned home to their daughter. They defected to the United States after a visit to Vienna in 1957, but soon returned to Hungary to care for Szekely’s aging parents.

Szekely retired from competition not long after the 1956 Olympics, and became a pharmacist and swimming coach. One of her most successful students was her daughter, Andrea, who went on to an Olympic swimming career of her own, winning a silver medal in the 100-meter backstroke and a bronze in the 100-meter butterfly at the 1972 Games in Munich.

Szekely accompanied her daughter to Munich, where she met a member of Israel’s Olympic delegation shortly before Palestinian terrorists killed him, 10 other Israeli athletes and coaches and a West German police officer.

Two years after the Munich attacks, Szekely spoke in a nationally televised interview about how she had responded in the early 1940s to questions about her background.

“Unequivocally, I was a Jew,” she said.

Eva Szekely was born in Budapest on April 3, 1927, to Andor and Maria (Schwitzer) Szekely. Her father owned a shop that sold metal goods, her mother was a homemaker, and Eva’s fascination with swimming began when she was quite young.

“Water was the real world where I really felt comfortable and absolutely safe,” she said in an interview provided by the Hungarian Swimming Association. “I usually said that I should have been a fish.”

Her love of competitive swimming grew after a fellow Hungarian, Ferenc Csik, won a gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin.

She studied pharmacology at Semmelweis University and what is now the University of Physical Education in Budapest. Her marriage to Gyarmati ended in divorce. In addition to her daughter she is survived by a grandson, Mate Hesz, a talented water polo player; and a great-granddaughter.

© 2020 The New York Times