On a recent afternoon at the Lao Thai Kitchen restaurant, the telephone rang and the caller ID read “Google Assistant.” Jimmy Tran, a waiter, answered the phone. The caller was a man with an Irish accent hoping to book a dinner reservation for two on the weekend.

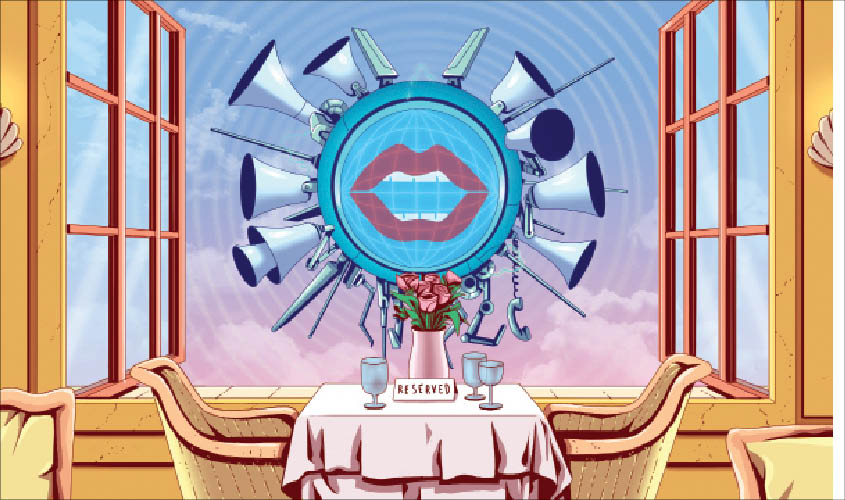

This was no ordinary booking. It came through Google Duplex, a free service that uses artificial intelligence to call restaurants and—mimicking a human voice—speak on our behalf to book a table. The feature, which had a limited release about a year ago, recently became available to a larger number of Android devices and iPhones.

The voice of the Irish man sounded eerily human. When asked whether he was a robot, the caller immediately replied, “No, I’m not a robot,” and laughed.

“It sounded very real,” Tran said in an interview after hanging up the call with Google. “It was perfectly human.”

Google later confirmed, to our disappointment, that the caller had been telling the truth: He was a person working in a call centre. The company said that about 25% of calls placed through Duplex started with a human and that about 15% of those that began with an automated system had a human intervene at some point.

We tested Duplex for several days, calling more than a dozen restaurants, and our tests showed a heavy reliance on humans. Among our four successful bookings with Duplex, three were done by people. But when calls were actually placed by Google’s artificially intelligent assistant, the bot sounded very much like a real person and was even able to respond to nuanced questions.

In other words, Duplex, which Google first showed off last year as a technological marvel using AI, is still largely operated by humans. While AI services like Google’s are meant to help us, their part-machine, part-human approach could contribute to a mounting problem: the struggle to decipher the real from the fake, from bogus reviews and online disinformation to bots posing as people.

Here are the results of our experiment.

Google’s AI is eerily human, when it works

To test Google Duplex, we used a pair of Google’s Pixel smartphones, which include the company’s virtual assistant by default. (Apple’s iPhone users can try Duplex by downloading the free Google Assistant app.) At the bottom of the screen, we pressed a button to summon the Google assistant and then said, “Book me a dinner reservation.”

Google’s assistant then loaded a list of nearby restaurants. For the restaurants that took reservations only over the phone, Google offered to step in and place the call with Duplex.

We tried using Duplex more than a dozen times. Several restaurants, like Henry’s Hunan in San Francisco and China Village in Albany, California, rejected our requests for a table of two to four people because they took reservations only for tables of 10 people or more.

Eventually, we secured four reservations in Albany: two separate reservations at Nomad Tibetan restaurant, one booking at Lao Thai Kitchen and one reservation at Bowl’d Korean Rice Bar. We witnessed or reviewed each of the phone calls, and the restaurants were made aware that we were testing Duplex before they picked up the phone.

Only the reservation at Bowl’d, which we witnessed at the restaurant, was made entirely with Google’s AI service. The bot introduced itself as Google’s automated booking service, followed by a request to book a table for Tuesday.

The call demonstrated the ability of Google’s AI operator to insert pauses and “ums” to mimic a human—in effect making the interaction feel more lifelike and less scripted.

At several moments during the call, the restaurant’s manager, Jin Park, acted confused and asked the caller to state the party size and reservation date. The bot patiently answered the questions again and again. Then, Park threw a curveball: “Are there any kids?”

The Google bot was quick to improvise: “I’m actually booking on behalf of a client, so I’m not too sure,” he said.

“Everything was perfect,” Park said in an interview after conversing with the Google bot. “It’s like a real person talking.”

Duplex needs lots of data to improve

In recent years, the development of AI has accelerated thanks to what are called neural networks, complex mathematical systems that can learn tasks by analysing vast amounts of data. By analysing thousands of dog photos, for instance, a neural network can learn to recognize a dog.

This technology has significantly improved a machine’s ability to recognise spoken words, understand how these words are used and even generate speech on its own. With Duplex, Google is combining these various tasks into a single system. It works because Google has focused on a small domain: restaurant reservations.

Building this kind of system requires large amounts of data, and Google may be using human callers to generate data that can help “train” future versions of the system.

Nick Fox, the Google executive overseeing its assistant, said the company was not aggressively trying to eliminate human involvement from Duplex because that could make the experience for business owners worse. Instead, he said, Google was trying to improve the automated system over time and slowly decrease the need for humans to intervene.

Not so smart after all

In an era of tech companies trumpeting the arrival of AI, today’s technology is not quite as intelligent as it might seem.

Mark Zuckerberg promises that AI can identify and remove toxic content from Facebook, but his company still employs thousands of humans to do the job. When Amazon boasts of all the robots in its distribution centres, blue-collar workers are sorting through all the stuff moving through those giant warehouses.

Duplex is proficient at making a restaurant reservation over the phone, but much like Facebook, Google still leans on human intelligence. At any given moment, it is lifelike. But it struggles to deal with the unexpected.

“There are three things that are important when it comes to AI’s interactions with humans: context, context and context,” said Jerry Kaplan, author of Humans Need Not Apply: A Guide to Wealth and Work in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and a Stanford University lecturer on artificial intelligence. “Machines are very good with detail but terrible at context,” he said.

© 2019 The New York Times